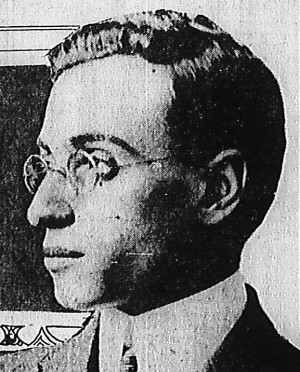

In 1982, Alonzo Mann dropped what appeared to be the biggest bombshell imaginable into the Leo Frank case — though it was sixty-nine years after the fact. Mann, who’d been Leo Frank’s fourteen-year-old office boy in 1913, stated that he had kept a secret all these years: He had returned–he claimed–to the National Pencil Company office around noon on the day Mary Phagan was murdered and saw the black janitor Jim Conley carrying Mary Phagan’s limp body. According to Mann, Conley had threatened to kill him if he told anyone what he saw, and his own parents advised him to tell no one. So Mann did keep quiet, and his silence resulted in the conviction and death of Leo Frank for the murder — a crime Mann he believed Jim Conley committed.

But can Mann’s story be believed? And if it can, does what he saw prove Leo Frank’s innocence? Let’s investigate:

Mann’s signed 1982 affidavit was a media sensation and convinced many readers that Leo Frank was an innocent victim. It was also the basis for two attempts by Jewish groups to obtain a posthumous pardon for Leo Frank, the second of which was successful.

According to Leonard Dinnerstein (“The Fate of Leo Frank,” American Heritage, October 1996, vol. 47, issue 6):

There is no reason to doubt that Alonzo Mann’s affidavit is accurate. Had he ignored his mother’s advice and gone to the police with his information right away, Conley would surely have been arrested, the police and district attorney would not have concentrated their efforts on finding Frank guilty, and the crime would most likely have been quickly solved. But by the time the trial began, in July 1913, Mann’s testimony might hardly have even seemed important.

What really happened in 1913? First, let’s look at Mann’s testimony at trial in 1913, from the Official Brief of Evidence:

Alonzo Mann: I am office boy at the National Pencil Company. I began working there [Tuesday] April 1, 1913. I sit sometimes in the outer office and stand around in the outer hall. I left the factory at half past eleven on April 26th. When I left there, Miss Hall, the stenographer from Montag’s, was in the office with Mr. Frank. Mr. Frank told me to phone to Mr. Schiff and tell him to come down. I telephoned him, but the girl answered the phone and said he hadn’t got up yet. I telephoned once. I worked there two Saturday afternoons of the weeks previous to the murder and stayed there until half past three or four. Frank was always working during that time. I never saw him bring any women into the factory and drink with them. I have never seen Dalton there. On April 26th, I saw Holloway, Irby, McCrary and Darley at the factory. I didn’t see Quinn. I don’t remember seeing Corinthia Hall, Mrs. Freeman, Mrs. White, Graham, Tillander, or Wade Campbell, I left there 11:30 [AM].

CROSS EXAMINATION:

When Mr. Frank came that morning, he went right on into the office, and was at work there and stayed there. He went out once. Don’t know how long he stayed out.

Now, fast forward to the 1980s. Alonzo Mann, one of the last surviving Leo Frank defense witnesses, came forward some sixty-nine years later, in 1982, and provided some sensational testimony.

According to a typical media account of the affidavit, this one from Georgia Public Radio, “Alonzo Mann, Frank’s former office boy, claimed he saw Jim Conley carrying the body of Mary Phagan into the lobby of the National Pencil Company. Mann, who was only fourteen at the time, said Conley threatened to kill him if he revealed what he saw. Terrified, Mann kept the secret for sixty-nine years.” That’s quite a terror, to last sixty-nine years — to continue while Conley was imprisoned as an accessory after the fact to the murder — and even to endure for some twenty years after Conley’s death. Quite a terror indeed. Georgia Public Broadcasting continues: “This new evidence encouraged members of Atlanta’s Jewish community to petition for a posthumous pardon for Frank. Attorneys at the Anti-Defamation League initiated the process which finally ended in a diluted victory in 1986. The Board of Pardons and Paroles did not address the question of guilt or innocence, but rather a pardon was issued based on the State’s failure to protect Frank from the hands of his assailants.”

The ADL and the Highly Political Posthumous Pardon

Alonzo Mann’s affidavit became the basis of an attempt to obtain a “posthumous pardon with exoneration” for Leo Frank from the Georgia State Board of Pardons and Paroles. The effort was led by Charles Wittenstein, southern counsel for the Anti-Defamation League, and Dale Schwartz, an Atlanta lawyer.

What do reason and common sense tell us?

The further away in time a memory is from the original event, the more likely it becomes distorted and easily manipulated. How would a 21st century State Supreme Court or United States Supreme Court weigh testimony that comes sixty-nine years after the fact? An even more salient question is: Could such a revelation as Alonzo Mann’s in 1982, even if true, be sufficient to exonerate Leo Frank? You decide.

Background: On April 1, 1913, thirteen-year-old Alonzo Mann was given a highly coveted job as Leo Frank’s personal office boy at the National Pencil Company. Given Mann only worked at the company for a total of three and a half weeks before the murder was committed, one is not inclined to believe he had known Leo Frank long enough to make an accurate character assessment. Moreover, one may suspect that the young office boy was a bit star struck and naive back then. A tenure of a little over three weeks is hardly enough to give him the right to pontificate on the “extracurricular activities” — or lack thereof — going on in the factory under Leo M. Frank for the previous five years.

Fast forward 69 years from 1913 to 1982, when the story broke.

In 1982 Alonzo Mann was in the twilight of his life, frail, and in terrible physical condition. Mann was perched on a cane and had a pacemaker, was on a cocktail of pharmaceuticals — and truly lonely. The WWI veteran had, sadly, outlived his wife and only son. His virtual “death-bed” revelation in the years before he died had all the flair of a fictionalized Hollywood or Broadway drama — and the markings of another backroom bribery deal, which has been the central strategy of Leo Frank’s defenders for a century. The Georgia Supreme Court records containing Leo Frank’s appeals reveal the birth of this ugly strategy.

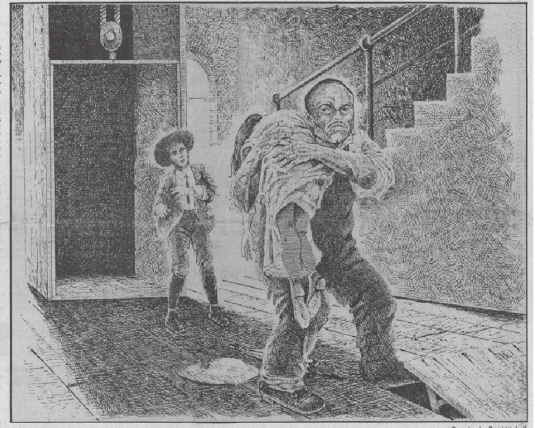

In 1982, Alonzo Mann changed his story and alleged that he really left the National Pencil Company factory at noon, instead of 11:30 am (as he had testified in 1913). He then went on to say that at 12:05 — five minutes after he left the factory — he came back and saw the 27-year old African-American janitor, Jim Conley, carrying the limp body of Mary Phagan on his shoulder, positioned as if getting ready to dump her down the two-foot-by-two-foot scuttle hole next to the elevator. Jim Conley then allegedly reached out for Alonzo Mann and said to the young boy, “if you tell anyone I will kill you.” Alonzo Mann claimed that he ran home and told his family, and alleges that his parents then told him not to tell anyone or get involved.

Does that seem logical? — or does that set off your highly refined nonsense detector?

Alonzo Mann’s 1982 statement does not pass multiple common sense tests, especially for those who know the history and culture of the South.

First: Why would white parents in the white racial separatist Atlanta, Georgia of 1913, tell their son not to tell the police about a murdering and guilty black janitor — especially when the result of not telling the police would ultimately result in an innocent, clean cut, and white boss, Leo Frank — a man who gave their son a highly prized job — going to the gallows? In the Old South, African-Americans were seen as prone to violent outbursts and were regarded as third class citizens with child-like mental and emotional maturity; and they were often not afforded the same legal protections as whites when accused of crime — and were usually easily convicted.

Second: Why would these white parents, in a white separatist South, allow their son to report back to work on Monday morning, April 28, 1913 — two days after that son was threatened with death by a black man carrying a dead white girl on his shoulder, knowing that that same black man would be there too? Jim Conley reported back to work that Monday, April 28, 1913, as did the 170 other employees, who were naturally expected to be back at work after the holiday weekend. Jim Conley was not arrested until Thursday, May 1st, 1913.

Third: If Alonzo Mann admitted to lying under oath at the Leo Frank trial in 1913 — “withholding information” and saying he left at 11:30 am instead of noon as he contended 69 years later — who’s not to say he wasn’t lying again in 1982 and beyond?

Fourth: If Alonzo Mann walked in on Jim Conley at 12:05 PM while Conley was getting ready to throw Mary Phagan’s body down the scuttle hole, why did Monteen Stover — who testified she came down the stairs near the front entrance and scuttle hole at exactly that time — not witness this scene also? Why didn’t Leo Frank — who was just 40 feet away — not hear Mary Phagan scream or any sounds of a struggle at all?

Fifth: If Alonzo Mann or his parents kept quiet because they were afraid of retribution from Jim Conley, why did they not tell the authorities what Alonzo had seen once Jim Conley was arrested? Conley was arrested on May 1, 1913, convicted of being an accessory after the fact in the murder of Mary Phagan, and remained imprisoned throughout the entire year of 1914.

Sixth: If Alonzo Mann was “terrified” into silence by Jim Conley, why did that terror not end in 1962, when Conley is reported to have died?

Let’s take a closer look

If we are to believe Alonzo Mann that he saw Jim Conley carrying the unconscious body of Mary Phagan, isn’t it rather odd that in the white racial separatist South of 1913 — given the likelihood of unrelenting and possibly prejudiced law enforcement, if not an extremely violent lynching — a Southern black man would assault, rob, and then possibly murder a teenage white girl in the highest traffic area in the factory, almost next to the unlocked glass-paneled front door? — and then, in the aftermath of the crime, carry her body across the same area without even bothering to lock the door?

During the trial, Leo Frank’s defense team changed its theory of how the attack against Mary Phagan transpired. According to one theory, Mary Phagan was crowded back into the empty Clarke Woodenware Company space on the first floor, assaulted, and thrown down a back chute at the rear of the building. But that theory encountered a problem: It was determined well before the trial that the owner of the building had locked the door to that area four months earlier, and the door was still locked when the police came to the premises on Sunday, April 27 — the day after Mary Phagan was killed. Later during the trial, the Leo Frank defense team said that Mary Phagan’s body was thrown 14 feet down into the basement via the two-foot wide scuttle hole near the elevator at the front of the building, which had a ladder diagonally going downward. In other theories, Jim Conley murdered Mary Phagan in the basement. The defense theories kept — and keep — changing.

Wouldn’t there have been forensic evidence on the body of a 4’11” 107-pound girl if she had fallen 14 feet? Mary Phagan had numerous autopsies performed on her by doctors in late April and early May of 1913, and none of the reports mention any broken bones or indications on her body that she had fallen 14 feet to a hard dirt floor. In fact the forensic evidence shows that the scratches on her face caused by her being dragged 150 feet across the basement floor — from the elevator to the rear of the cellar — had no blood coming from them, indicating she was already quite dead when she reached the basement.

The autopsy reports revealed Mary had died of strangulation and the black eye suggested a left-handed man had punched her in the face. What percentage of people are left-handed? According to Wikipedia.org, “A variety of studies suggest that 70–90% of the world population is right-handed.” (Wikipedia, “Lefthandedness, “2013). Since Leo Frank was left-handed and Jim Conley right-handed, who was more likely to have punched her in the right eye with a left fist?

And none of the defense theories give us any explanation at all of the hair which, along with dried blood, was found on the lathe in the metal room upstairs, nor for the blood stains found nearby on the metal room floor.

Another throwaway detail?

The most interesting piece of evidence Alonzo Mann provided to the public in 1982 was that concerning the location of the “loafing sweeper” Jim Conley. Mann said Conley was idly squatting on a box in the first floor lobby of the National Pencil Company for the entire morning of Saturday, April 26, 1913. That’s a very interesting piece of evidence because, in 1913, Alonzo Mann and several of Leo Frank’s other defense witnesses claimed they didn’t see Jim Conley that day. It would mean that Hattie Hall, Leo Frank’s stenographer, had committed perjury and lied under oath — as well as N.V. Darley, Alonzo Mann himself, and everyone else who was a defense witness for Leo Frank that had claimed to be in the factory that morning.

This “new” evidence provided by Alonzo Mann was not actually new, and did not actually help Leo Frank, but tended to corroborate all the other eyewitness testimony from others who were there at the factory that morning, who said that a black man (some specified him as Conley, some didn’t) was idly loafing about in the lobby. The eyewitness testimony tended to suggest that Jim Conley had indeed spent the morning and afternoon in the factory lobby and Leo Frank not only knew about it, but had indeed requested his African-American assistant to come to work on that infamous day — but it was a very curious kind of work, as we shall see.

Did Jim Conley’s testimony sustain itself?

Jim Conley alleged he was waiting in the lobby all morning long because Leo Frank had asked him to wait there as a watchdog for him during an anticipated afternoon tryst. Is there an unwritten subtext here? Jim Conley claimed to have served as Leo’s watchdog on numerous other Saturdays while Frank “entertained” other girls. Did Leo Frank have a pre-planned tryst arranged with Mary Phagan? If so, it adds a new dimension to the case never before explored. For the purposes of history, if we consider the Konigsberg variation of the murder — that Mary Phagan had a pre-arranged tryst with Leo Frank — then it opens up the possibility that this case is even more bizarre than we might have ever thought. And if the Konigsberg variation is true, why then did Leo Frank murder Mary?

Did Leo Frank lie about not knowing Jim Conley was at the factory that day?

If Alonzo Mann was indeed telling the truth about Jim Conley sitting near the factory entrance all morning long doing nothing on the morning of the murder, it definitely suggests that Leo Frank might have lied to the court when he gave his unsworn statement to the jury: Frank said he did not even know Jim Conley was in the factory at all on the day of the murder. (Leo Frank Trial Statement, Brief of Evidence, August 18, 1913)

How could Leo Frank not know Jim Conley was there, when Leo Frank admitted at the trial that during the morning he left the building and came back after running morning errands, including a brief trip to Sigmund Montag’s office down the block to get the mail? (Leo Frank, Brief of Evidence, August 18, 1913). How could Leo Frank miss seeing someone sitting next to the staircase he would have traversed at least twice, coming and going?

The common sense test

If Leo Frank did not know Jim Conley was there, a logical question follows: What was an employee of the factory, Jim Conley, who was not required to work on this Saturday — a state holiday — doing, sitting on a crate next to the staircase on the first floor lobby all morning long, wasting time watching people come and go? Why would a sweeper like Jim Conley go to work on a Saturday, a state holiday and day off — unless he was required to do so by his boss? This an especially pertinent question in light of the fact Jim Conley had been paid his weekly salary — $6.05 — the evening before, on Friday, April 25, 1913 by Leo M. Frank. At five cents a beer and three cents a whiskey, it’s hard to imagine Jim Conley would have spent all of his salary on liquor the night before and still come to work bright and early the next day. And it certainly doesn’t seem realistic that Jim Conley could have drunk 120 beers the night before and would therefore need to rob, rape, and strangle a White girl for her $1.20 pay — especially at the highest traffic point of the National Pencil Company factory, right next to an unlocked, half-glass, entrance door. Wouldn’t he rather have spent his time drinking five cent pints at any agreeable saloon?

Jim Conley coming to work on his day off just doesn’t fit or make sense, unless he was asked to come to work by his boss, Leo Frank. And, if he was asked to come to work, why wasn’t he working, at least in any visible way? Could it be that by just sitting and watching the comings and goings at the factory entrance, he was doing exactly what Leo Frank had asked him to do?

Concerning Jim Conley’s unheard-of salary

When it was revealed, Jim Conley’s unusually high salary for his menial position left many people asking why this African-American floor sweeper — who’d been demoted from elevator operator — was making 50% more ($6.05 vs $4.05) than the white children day laborers. Perhaps Jim Conley was more than just a floor sweeper. Perhaps this fact sustains all the testimony which confirmed Jim Conley was Leo Frank’s “watchdog,” keeping a careful eye on the entrance when Leo would order call-in prostitutes from Nina Formby on Saturdays or arrange trysts with his quite-possibly-willing girl-child laborers who were living on the edge of poverty. Furthermore, given that one female employee reported at the Frank trial that she told assistant superintendent Herbert George Schiff (Trial Testimony of Herbert George Schiff, Brief of Evidence, August, 1913) that Jim Conley was “sprinkling” (urinating) on the pencils, why was he never fired? Could it be that Jim Conley served a very important purpose for Leo Frank? Could it also be that he knew too much to be fired?

Schiff would claim at the trial that the reason why Jim Conley wasn’t fired was because “he knows the business too well” — a very strange statement indeed to make of a sweeper! (Brief of Evidence, 1913).

According to another Black employee, “Snow Ball” (Gordon Bailey, Brief of Evidence, August, 1913), Jim Conley was — unlike every other worker except executives — not always required to punch the time clock. Why would a sweeper like Jim Conley — who’d been “busted” down to the lowest job in the factory — be extended such unique liberties by Leo M. Frank? Why was Jim Conley the only person out of the 170 hourly factory employees — most of whom were white and some eight of whom were African-Americans — not to have to punch the time clock?

A scream in broad daylight

The defense and Leo Frank partisans contend that Jim Conley was waiting in the lobby all morning until a little after noon in order to rob a fellow employee, Mary Phagan. But they forgot about the scream.

Where Jim Conley sat on the first floor was no more than 30 to 40 feet from where Leo Frank sat in his inner office on the second floor. And the first floor lobby of the National Pencil Company was the highest traffic point in the entire building: It was where people would come and go all day long during the work week, and all morning long on Saturdays.

On Saturday, April 26, 1913, people were coming to collect their pay envelopes and several employees were present in the morning for a half-day’s work. Leo Frank was on the second floor, in his office, on April 26, 1913, as he was on most Saturdays. He surely could have heard a scream from 30 to 40 feet away, had there been one. Jim Conley, in fact, claimed he heard a scream after Leo and Mary went to the metal room, a considerably greater distance than Frank’s office. Leo Frank did not mention a scream at all.

If Jim Conley had attacked Mary Phagan in the lobby, Leo Frank would almost certainly have heard a scream directly below him. He could then have easily called the police, as the telephone was inside Frank’s office on the wall. (See Defense diagrams of the second floor).

The theory of Jim Conley beating, robbing, and “possibly raping” a white girl in the place where Monteen Stover would likely have walked in on him doing it, would almost surely guarantee Monteen’s backing up into a street filled with white men — and then, for Jim Conley, a castration without anesthesia, or worse, would ensue. This is how men of color accused of raping white girls were generally treated in 1913 Atlanta — that is, just before they were lynched from a tree or riddled with bullets. Imagine how it would have fared for one such not merely accused — but caught in the act!

Was Jim Conley telling the truth when he said Leo Frank asked him on the previous evening — Friday, April 25, 1913 — to come to work on the morning of April 26 to act as a watchdog as he had in the past? This was something Leo M. Frank had done many times before on Saturdays, according to Jim. Naturally, given the obvious implications, Leo Frank denied it. What man, guilty or innocent, would not deny callously arranging sexual trysts with women (sometimes even little girls) other than his wife? Which brings us back full circle to the question: Why was Jim Conley sitting on that crate all morning long in the factory lobby on his day off?

Jim Conley’s sitting on that crate next to the stairs was corroborated by Mrs. White at the trial in 1913, and later by Alonzo Mann in 1982 — though not in 1913.

Common sense tells us that usually no one goes to work on a state holiday or day off unless asked to do so, or for some other really compelling reason. So the question is: Who asked Jim Conley to spend the day waiting and sitting on a box on the first floor lobby area of the National Pencil Company? If someone didn’t ask him, what was he doing there all day? Waiting to rob someone at high noon, right by the glass-windowed front door and while the streets were filled with people? Jim Conley says Leo Frank did ask him, as he had many times before, to act as a lookout while he “chatted” with girls in his office — and numerous witnesses other than Alonzo Mann sustained the fact Jim Conley was actually sitting there all morning long.

Alonzo Mann never mentioned seeing Tillander, Corrie, or Emma — thus sustaining his original statement he left the Factory at 11:30 AM on April 26, 1913 — not the supposed noon he claimed 69 years later. Another interesting statement at trial was that of Hattie Hall, Frank’s stenographer: She did not mention seeing Alonzo Mann when she left at noon, supporting therefore the idea that Alonzo Mann did leave the factory at 11:30 and not at noon.

Alonzo Mann claimed he came back to the factory at 12:05 pm — almost immediately after supposedly leaving at noon — because he wanted to speak to Herbert George Schiff. But evidence suggests that Schiff was never expected to be at work on this holiday and, in fact, he never showed up — a fact which no one disputes. This casts further doubt on Alonzo Mann’s story about coming back and seeing Conley in the act of carrying Mary Phagan’s body.

Isn’t it rather odd that Herbert G. Schiff — who prided himself at the trial concerning the fact he never missed a day of work for five years — would have said he supposedly “missed work” on Saturday, April 26, 1913, a state holiday — when he was almost certainly not expected to come to work at all? (see: Trial testimony of Herbert G. Schiff, Brief of Evidence, August, 1913). Alonzo Mann claimed he called Herbert Schiff one time that morning, but the Schiff’s maid alleged Alonzo Mann had called twice. Did he even call at all? What caused the mix-up? The cacophony was even bigger than described here: Others claimed to have called Herbert George Schiff at different times that morning, but there’s no real reason to believe Schiff was expected to come in that day by anyone.

It turns out that Schiff was indeed called during the morning of April 26, 1913 — but not to report to work: He was called to inform him his suit had come from the dry cleaners.

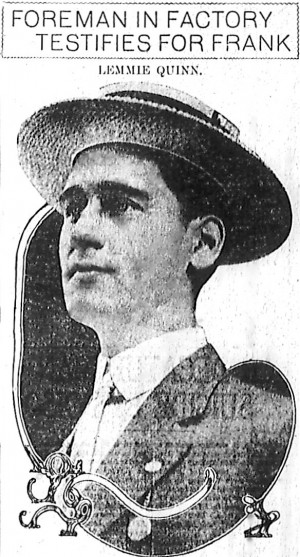

Lemmie Quinn: The metal room foreman’s story

The other problem Leo Frank had to contend with was the issue of Lemmie Quinn, who allegedly came to the factory at 12:20 PM on April 26, 1913, supposedly for two minutes, looking for Herbert George Schiff in order to talk about a baseball bet with him. Why was Lemmie Quinn looking for an employee at 12:20 PM on Saturday, April 26, 1913, who was never supposed to come to work on a holiday?

Leo Frank said he had forgotten for a full week to mention Lemmie Quinn’s afternoon arrival at the factory at 12:20 PM and Coroner Paul Donehoo, at the Coroner’s Inquest, asked why he didn’t mention this important information to the police once he remembered it a week later. Leo Frank responded by saying he wanted to ask for permission from his lawyers first before revealing it to police. Donehoo was incredulous, as might be expected.

Donehoo and others doubtlessly reasoned that someone accused of murdering a little girl would make every effort to bring forward exonerating evidence and alibi witnesses as soon as humanly possible — and not withhold such evidence for more than a week. The result of Leo Frank waiting more than a week to tell anyone made the new evidence appear as if it was manufactured, especially in light of the fact that an affidavit was made by Lemmie Quinn a week before the Coroner’s inquest, stating he had left the factory at 11:45 AM to go home and then head to a billiards hall on the other side of town.

Lemmie Quinn’s “reappearance” at the factory at 12:20 PM on April 26, 1913, was seen as a physical impossibility given that Lemmie admitted leaving the National Pencil Company at 11:45 AM, going home and then making a 25 minute trip to the billiards hall. This would not have given Lemmie Quinn enough time to get back to the factory at 12:20 PM, even if Lemmie Quinn only played one quick game and then made the 25 minute trip back to the factory.

Lemmie Quinn backfired

Lemmie Quinn got caught in a lie and it was likely that none of the 12 jury members nor Judge Leonard Strickland Roan believed him. Quinn gave testimony that came off as fabricated after the murder for the purpose of shrinking the amount of time available for Leo Frank to kill Mary Phagan — from noon to 12:35, down to the range of noon to 12:19.

Quinn’s claims boxed in Leo Frank

The notable thing about Lemmie Quinn’s supposed appearance at the factory at 12:20 PM is not only that our highly refined fraud detectors tell us that his story might have been a fabrication to help Leo Frank, but more importantly that it makes the defense’s “first floor attack” on Mary Phagan even more difficult to believe. If Alonzo Mann really saw Jim Conley carrying the unconscious body of Mary Phagan in the lobby at 12:05, where was Monteen Stover? And since Leo Frank changed the time he claimed Mary came to his office to 12:12 to 12:17, and further claimed he spoke to her for two or three minutes, why didn’t she bump into Lemmie Quinn upon exiting? Both Stover and Quinn claimed to be at the factory sandwiching the time Leo Frank said Mary Phagan arrived, so wouldn’t have Quinn bumped into at least Mary Phagan or Jim Conley at 12:20?

Leo Frank’s ever-changing times of Mary Phagan’s arrival

Frank gave several different times for Mary Phagan’s arrival at his office: 1) “12:02 to 12:03” (The time he gave police orally on Sunday, April 27, 1913); “12:05 to 12:10, maybe 12:07” (The time he gave in a deposition to police on Monday, April 28, 1913 known as State’s Exhibit B, 1913); then it became “12:10 to 12:15” (The time he gave at the Coroner’s Inquest, May 5 and 8th, 1913); and finally “12:12 PM to 12:17 PM.” (Leo Frank Trial, August 18, 1913).

These ever-latening time claims damaged Frank’s credibility beyond repair, and, to make matters worse, all of these times were during a time period he could not account for, even with Lemmie Quinn’s “boxing him in” at 12:20. One thing is obvious: If Frank’s later time claims are regarded as true, then Alonzo Mann’s 1982 affidavit is false. They are mutually exclusive.

Nothing significant; nothing new

A most salient point is this — as even pro-Frank researcher Steve Oney admits: Alonzo Mann brought absolutely nothing new to the Leo Frank Case with his 1982 affidavit. Jim Conley had already admitted to being an accomplice and admitted that he participated in bringing the dead body of Mary Phagan to the basement — at Leo Frank’s request. If he was seen carrying Mary Phagan in the lobby, it only invalidates Conley’s claim that he exclusively used the elevator to do so, and the rest of Conley’s testimony remains unchallenged.

A dead man’s affidavit

However, the ADL of B’nai B’rith, the American Jewish Committee, the Atlanta Jewish Federation, and numerous other Jewish organizations used the affidavit of Alonzo Mann, even after his death, to push for a posthumous pardon with exoneration for Leo M. Frank.

First attempt: failure

Attorneys for these three Jewish organizations petitioned the (Georgia) State Board of Pardons and Paroles to pardon Leo Frank, but the petition was denied on December 22, 1983.

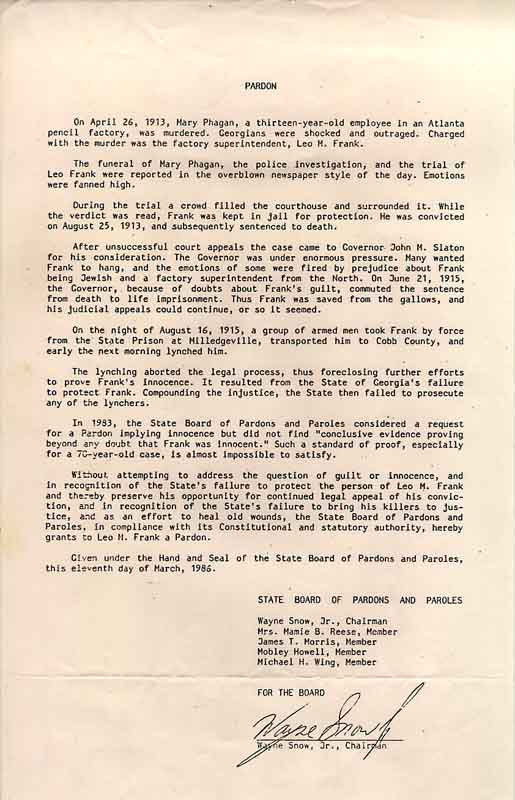

Pardon without exoneration: achieved

A Pyrrhic victory for the Jewish Community resulted, after successful pressure from the ADL and other Jewish organizations, on March 11, 1986. The State Board of Pardons and Paroles pardoned Leo M. Frank due to the failure of the state to protect him from lynching — but they would not exonerate him of the crime of murder. It was an odd appeasement.

In a way, this decision was ultimately another victory for the prosecution team: Leo Frank’s murder conviction is still standing today as “black letter” and settled law, with permanent and binding legal precedent. Even after decades of relentless propaganda and behind the scenes wheeling and dealing by Jewish groups, the ultimate result was that the jury had the last word.

The Jewish community — and the media — present the pardon at face value as a vindication of Leo Frank. But consider another view: In order to pardon someone of a crime, that person has to be guilty — you can’t pardon someone unless you first acknowledge his guilt. Therefore, the guilt of the individual has to be affirmed — and in Leo Frank’s case it was affirmed again and again, at every level of the appellate system. All, including the State Board of Pardons and Paroles, preserved his verdict of guilt.

Further appeals?

The pardon was granted, the Board said, because the state failed to protect Leo Frank and because his lynching prevented him from launching further appeals. But there is one little problem with that.

The Board members were patently in error when they alleged that the lynchingprevented Frank from making any further appeals within the appellate court system, because Leo M. Frank had fully and totally exhausted all of his court appeal options at every level of the State, District, and Federal Appellate Courts, with the Supreme Court unanimously overruling any further review of the case, thus closing the door forever at all levels of the appellate court system. When there were no more options left in the court system, the State Board of 100 years ago refused a recommendation of clemency — and even the likely-bribed Governor John M. Slaton, refused to pardon Leo Frank and actually stated in his commutation letter he was not disturbing the guilty verdict. Not a single legal body in the last century has overturned the guilty verdict of Leo Frank, but attempts to spin the truth have endlessly been made.

Conclusion

Far from being the “bombshell” that “broke the Leo Frank case” and “proved Leo Frank to be innocent,” Alonzo Mann’s 1982 affidavit is a very doubtful document that, even if true, provides essentially nothing new to the objective student of the case. What it has provided, though, is an emotion-laden propaganda weapon for those who have been deceiving the public about this case for a century now.

* * *

APPENDIX: Articles and Images

_______

from the Dubuque Telegraph-Herald, March 8, 1982:

Man breaks 69-year silence on sensational murder case

NASHVILLE, Tenn. (UPI) — For almost 70 years Alonzo Mann kept secret his information that could have saved a Jewish factory superintendent from being lynched for killing a 14-year-old girl in Georgia.

As a 13-year-old boy he was afraid to testify at the trial of Leo Frank because the prosecution’s star witness — who Mann says was the real murderer — threatened to kill him. Mann said he later kept quiet because his mother told him not to get involved.

After he was convicted Frank was taken from prison and lynched in the sensational case that sparked waves of anti-Semitism and led to the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan and the creation of the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith.

“At last I am able to get this off my heart,” Mann, 83, said in a copyrighted interview in Sunday’s Tennessean newspaper.

There will be some people who will be angry at me because I kept all this silent until it was too late to save Leo Frank’s life,” said Mann, who passed both a lie detector test and a psychological stress evaluation test on the truth of his statement.

“When my time comes, I hope that God understands me better for having told it. That is what matters most.”

Frank was tried and convicted for the murder of Mary Phagan who worked at the pencil factory where he was the superintendent.

Mann’s account, contained in a sworn affidavit, claimed he saw the state’s star witness, Jim Conley, carrying the limp body of the victim on the day of the murder. Conley died in 1962.

Mann, who now lives in Bristol, Va., said he remained silent at first because Conley threatened to kill him and later because his parents told him not get involved.

“I believe in the sight of God that Jim Conley killed Mary Phagan to get her money to buy beer,” said Mann. “Leo Frank was innocent.”

Mann, who has a heart condition and fears his life is drawing to its end, was Frank’s office boy in April 1913 at the National Pencil Co. factory in Atlanta. Mary Phagan was killed at the factory when she went to collect the $1.20 she was owed for 10 hours work.

After the slaying, authorities arrested Frank. Conley, a janitor at the factory, became the star witness.

Mann said when he saw Conley carrying the girl’s body, she was apparently still alive. He told the Tennessean he believes that if he had cried out, he might have saved the girl’s life.

But he did not, and Conley told him, “If you ever mention this, I’ll kill you,” Mann said.

Frightened, Mann ran away and later told his mother what happened, he said. She told him to remain silent.

Georgia Gov. John Slaton commuted Frank’s sentence in 1915 from death to life in prison, an act that touched off a wave of outrage and mob violence. Armed mobs roamed Atlanta streets for days, forcing Jewish businessmen to close their doors.

Later, a group of 75 men calling themselves “Knights of Mary Phagan,” met at the girl’s grave and vowed to avenge her death. A couple of weeks later, they stormed the prison where Frank was being held, held guards at bay with rifles and took Frank away in handcuffs.

He was hanged from an oak tree near the house where Phagan was born. No one was ever charged with lynching Frank.

Two months after the lynching, the Knights of Mary Phagan reorganized and burned a cross on top of Stone Mountain in Georgia — an event that marked the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan.

“I wish I had told what I knew,” said Mann “But I never thought Mr. Frank would be convicted. And once he was convicted, I was sure he would eventually get out of it.”

_______

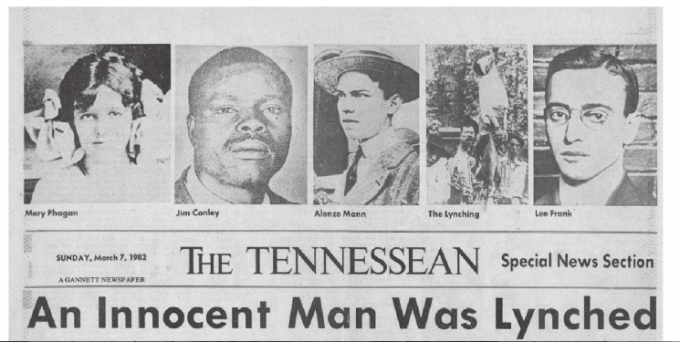

from the Nashville Tennessean, March 7, 1982 (front page):

AN INNOCENT MAN WAS LYNCHED

by Frank Ritter, Jerry Thompson and Robert Sherborne

Leo Frank, convicted in 1913 and lynched in 1915 in one of the most notorious murder cases in American history, was innocent, according to a sworn statement given by a witness in the case.

The testimony used to convict Frank was perjured, and the real killer of 14-year-old Mary Phagan was the man who gave that false testimony, the witness has disclosed to The Tennessean.

ALONZO MANN OF Bristol, Va., is the witness. Now 83 and ailing with a heart condition, he was Frank’s office boy in 1913 at the National Pencil Co. factory in Atlanta. It was there on Confederate Memorial Day in April that little Mary Phagan was slain when she went to collect the $1.20 she was owed for 10 hours of work the previous Monday.

“Leo Frank did not kill Mary Phagan,” Mann said, “She was murdered instead by Jim Conley.”

Mann’s memory is not perfect when he is recalling people, places and events of nearly 70 years ago. But he remembers vividly the confrontation with Jim Conley, who had the limp form of Mary Phagan in his arms.

Mary’s battered body was found face down on a pile of sawdust shavings in the factory basement. A cord was knotted around her neck and there was massive bleeding from a deep wound to her head. Cinders were found under her fingernails, showing she had clawed the ground in her struggles. Her underclothing was ripped but there was no evidence indicating she had been raped.

THE SLAYING shocked Atlanta and, after an investigation, police arrested Frank, the Jewish superintendent of the factory. The prosecution’s star witness was Jim Conley, who worked at the factory as a sweeper. He said Frank committed the murder.

But Mann has told The Tennessean that he saw Conley on the day of the murder with the limp body of Mary Phagan in his arms. He believes he saw this only moments after Mary had been knocked unconscious, but apparently before she was murdered. And he believes that if he had yelled out, he might have saved Mary’s life.

But Mann says he did not yell out, and that Conley told him:

“IF YOU EVER MENTION this, I’ll kill you.”

He was frightened and ran out, Mann says. After riding a trolley home, he told his mother what had happened. She directed him to remain silent and told him not to get involved. He obeyed her.

Mann’s statement puts him in direct conflict with the testimony to which Conley swore during the trial. Conley testified he was ordered by Frank to dispose of Mary Phagan’s body by burning it in the basement’s furnace. He said he and Frank were together the whole time they took the body from the second floor of the factory directly to the basement, using the elevator. He said he was not on the first floor with the body.

MANN, HOWEVER, says he saw Conley alone with Mary Phagan on the first floor of the building, standing near the trapdoor that led to the basement. It later became apparent — after the trial — that the elevator did not go to the basement that day. This fact was cited as crucial by Georgia Gov. John Slaton when he commuted Frank’s sentence in 1915 to life imprisonment.

There is no way that what Mann says today can be reconciled with the version of events which Conley related in court in 1913. Either Conley lied then, or Mann is lying now.

Because of the historical significance of what Mann is saying, The Tennessean asked him to submit to both a lie detector test and a psychological stress evaluation examination — procedures designed to determine if someone is lying. The tests were given by the Ball Investigation Agency here, and investigator Jeffery S. Ball provided the newspaper with a formal statement saying Mann responded truthfully to every question he was asked.

THE TENNESSEAN, after an extensive investigation which included the examination of files and records in several states and interviews with people knowledgeable about the case, concluded that Mann’s story needed to be made public.

This is the first time that Mann has spoken publicly about what he knows of the brutal murder which led to the most blatant display of anti-Semitism in the nation’s history and to a revival of the Ku Klux Klan — an irony because Conley, the chief witness, was a black man.

Mann says he told relatives and friends about what he knew. Once, while in the Army, he got into a fight with another soldier who disputed his statement that it was Conley and not Frank who killed Mary Phagan. And he tried once to tell his story to an Atlanta reporter.

FOR NEARLY 70 years his story has been a secret, and it has preyed on his mind. Now that he perhaps does not have long to live, it is vitally important that the truth come out, he told The Tennessean.

“I want the world to know the truth,” Mann explained in a series of interviews with the newspaper, “The testimony which Conley gave at the trial to convict Frank was a lie from beginning to end.”

That trial, surrounded by mob hysteria and violent anti-Jewish sentiment, was the most sensational in Atlanta’s history. No other trial even comes close, except perhaps that of Wayne Williams, convicted a week ago in the deaths of two young Atlanta blacks and suspected of being the mass murderer who terrorized Atlanta for months.

ALTHOUGH MARY PHAGAN was not raped, Frank was denounced as a sexual pervert; however, Conley was the only witness to suggest that.

The star prosecution witness made four separate statements to police in connection with the case, the first one saying nothing to implicate Frank. However, each of the three statements that followed increasingly involved Frank.

During the trial, it was the fourth and last statement that formed the basis for Conley’s court testimony. On cross-examination he repeatedly acknowledged that he had made numerous mistakes in his earlier statements to police, but efforts by the defense to break down his tale were largely unsuccessful.

FRANK WAS FOUND guilty and sentenced to hang, but appeals delayed the execution. Two years later his sentence was commuted to life in prison after the case had created a furor across the nation.

At that point — August 1915 — a group of vigilantes stormed the prison where Frank was being held, abducted him at gunpoint and lynched him.

Four blacks had been lynched in Georgia the month before.

Although he possessed information in 1913 which he believes would have cleared Frank, Alonzo Mann did not tell authorities what he knew. He says he did not speak out because Conley threatened to kill him if he did and because his mother and father convinced him he should keep silent.

NOW, FINALLY, HE has come forward with his story.

“I wish I had done it differently,” he says, “I wish I had told what I knew. But I never thought Mr. Frank would be convicted. And once he was convicted, I was sure he would eventually get out of it. I knew he was not guilty.

“I never fully realized until I was older that if I had told what I knew Leo Frank would have been acquitted and gone free. Instead he was imprisoned. After he was convicted, my mother told me there was nothing we could do to change the jury’s verdict. My father agreed with her. [front page ends here; no further transcription available at this time — Ed.]

_______

from the Tuscaloosa News, March 8, 1982:

Was innocent man lynched?

NASHVILLE, Tenn. (AP) — An 83-year-old man who says he wants to clear the record before he dies claims the wrong person took the blame for the 1913 death of 14-year-old Mary Phagan in a sensational Atlanta murder case, The Nashville Tennessean reported in a copyright story Sunday.

NASHVILLE, Tenn. (AP) — An 83-year-old man who says he wants to clear the record before he dies claims the wrong person took the blame for the 1913 death of 14-year-old Mary Phagan in a sensational Atlanta murder case, The Nashville Tennessean reported in a copyright story Sunday.

Alonzo Mann of Bristol, Va., told the morning newspaper that he is certain Leo Frank, a Jewish pencil manufacturer, was innocent of Miss Phagan’s murder.

Mann, who worked as an office boy at the National Pencil Co., in Atlanta in 1913, said he believed Jim Conley, a black sweeper at the company and the key prosecution witness in the case, killed the young white girl April 26, 1913, for her $1.20 pay to buy beer.

Conley, who died in 1962, maintained throughout the trial that he and Frank were together the whole time when the body of Mary Phagan was disposed of.

Frank was convicted and was sentenced to death, but his sentence was commuted by Georgia Gov. John Marshall Slaton, the newspaper said. In August 1915, a group of vigilantes who called themselves the Knights of Mary Phagan stormed the Milledgeville, Ga., jail where Frank was held and dragged him out at gunpoint. Frank was lynched about 175 miles away in an oak grove near Marietta, Ga.

The trial was flamed by anti-Semitism and spurred a resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan and the birth of the B’nai B’rith Anti-Defamation League, which opposes anti-Semitism.

Mann told the newspaper that he has thought often in the ensuing decades that he might have saved Mary Phagan’s life or that of Leo Frank.

Mann said he worked April 26, 1913, and left briefly to attend the Confederate Memorial Day parade with his mother. When he was unable to find her, he returned to the job and came across Conley, alone, apparently moments after the murder had been committed.

“I had no idea that I was about to witness an important moment in a famous murder case — a moment that has not been made public until now; that I was about to become a witness to tragic history,” Mann told The Tennessean.

Mann said he saw Conley holding the limp girl near a trap door leading to the factory’s cellar.

The Virginia man said if Miss Phagan was only unconscious when he saw her with Conley and if he had yelled for help, she might have been spared.

“On the other hand, I might have lost my own life,” he said, “If I had told what I saw that day I might have saved Leo Frank’s life. I didn’t realize it at the time. I was too young to understand.”

Mann said Conley had threatened him.

“He wheeled on me and in a voice that was low but threatening and frightening to me, he said:

“If you ever mention this I’ll kill you.”

“I was young and I was frightened, “ he told the newspaper. “I had no doubt Conley would have tried to kill me if I had told that I had seen him with Mary Phagan that day.”

Mann, who told The Tennessean he refused to give Conley a dime for two beers the morning of the murder, said Mary Phagan went to Frank a short time later to get her pay.

“I am convinced that she left the pay window and was coming down the stairs or had reached the first floor when she met Conley … I am confident that I came in just seconds after Conley had taken the girl’s money and grabbed her. I do not think sex was his motive. I believe it was money. Her pay was never found in the building after she died.”

Mann, who told the newspaper that by telling his tory he could at last “get this off my heart,” said he told his late wife about the crime, fought a soldier over the story and tried to tell an Atlanta newspaper reporter about it in the 1950s.

“I believe it will help people to understand that courts and juries can make mistakes. They made a mistake in the Leo Frank case. I think it is good for it all to come out at this date,” Mann said.

“I am making this statement because, finally, I want the record clear. I want the public to understand that Leo Frank did not kill Mary Phagan,” Mann, told The Tennessean in a story written by Frank Ritter, Jerry Thompson and Robert Sherborne, “Jim Conley, the chief witness against Leo Frank, lied under oath … I am convinced that he, not Leo Frank, killed Mary Phagan.”

John Seigenthaler, president and publisher of The Tennessean, said Mann passed two lie detector tests administered by Ball Investigative Agency. He said he insisted Mann be given a psychological voice stress test because he has a pacemaker which Seigenthaler was concerned would interfere with the lie detector tests. He said the agency told him the pacemaker would have no effect on the tests and Mann passed the voice analysis.

Mann said that fateful April day he told his mother what he had seen at the factory, but she told him to forget it in hopes of protecting the family and her son from publicity.

“After he was convicted my mother told me there was nothing we could do to change the jury’s verdict,” Mann said “My father agreed with her. I continued to remain silent.”

Mann, who testified at the trial, told The Tennessean he was nervous and frightened the day the trial started.

“There were crowds in the street who were angry and who were saying that Leo Frank should die,” he said, “ Some were yelling things like, ‘Kill the Jew!’”

“I never fully realized until I was older that if I had told what I knew Leo Frank would have been acquitted and gone free,” Mann told the newspaper. “Instead, he was imprisoned.”

Mann said neither he nor his father believed Frank would be convicted. Frank, who took the witness stand in his own defense, denied he killed the girl.

“Leo Frank was convicted by lies, heaped on lies,” he told the newspaper. “It wasn’t just Conley who lied. Others said that Leo Frank had women in the office for immoral purposes and that he had liquor there. There was a story that he took women in the basement … That was all false.”

Mann told the newspaper he believes people will have different reactions to his story.

“There will be some people who will be angry at me because I kept all this silent until it was too late to save Leo Frank’s life,” he said. “They will say that being young is not an excuse. They will blame my mother. The only thing I can say is that she did what she thought was best for me and the family.

“Other people may hate me for telling it. I hope not, but I am prepared for that, too. I know that I haven’t a long time to live. All that I have said is the truth.

“When my time comes, I hope that God understands me better for having told it. That is what matters most,” Mann said.

_______

The 1986 pardon of Leo Frank: