Originally published by the American Mercury on the 100th anniversary of the Leo Frank trial.

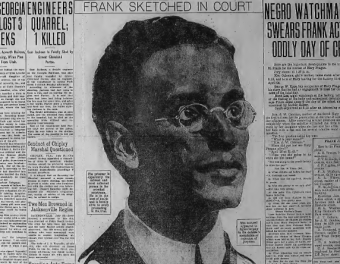

Take a journey through time with the American Mercury, and experience the trial of Leo Frank (pictured, in courtroom sketch) for the murder of Mary Phagan just as it happened as revealed in contemporary accounts. The Mercury will be covering this historic trial in capsule form from now until August 26, the 100th anniversary of the rendering of the verdict.

by Bradford L. Huie

THE JEWISH ANTI-DEFAMATION LEAGUE (ADL) — in great contrast to the American Mercury and other independent media — has given hardly any publicity to the 100th anniversary of the murder of Mary Phagan and the arrest and trial of Leo Frank, despite the fact that these events eventually led to the foundation of the ADL. Probably the League is saving its PR blitz for 1915, not only because that is centenary of Leo Frank’s death by lynching (an event possibly of much greater interest to the League’s wealthy donors than the death of Mary Phagan, a mere Gentile factory girl), but also because encouraging the public to read about Frank’s trial might not be good for the ADL — it might well lead to doubts about the received narrative, which posits an obviously innocent Frank persecuted by anti-Semitic Southerners looking for a Jewish scapegoat.

For readers not familiar with the case, a good place to start is Scott Aaron’s summary of the crime, from his The Murder of Mary Phagan and the Lynching of Leo Frank, which states in part:

“ON SATURDAY morning at 11:30, April 26, 1913 Mary Phagan ate a poor girl’s lunch of bread and boiled cabbage and said goodbye to her mother for the last time. Dressed for parade-watching (for this was Confederate Memorial Day) in a lavender dress, ribbon-bedecked hat, and parasol, she left her home in hardscrabble working-class Bellwood at 11:45, and caught the streetcar for downtown Atlanta.

“Before the festivities, though, she stopped to see Superintendent Leo M. Frank at the National Pencil Company and pick up from him her $1.20 pay for the one day she had worked there during the previous week….

“Almost no one knew it at the time, but by one o’clock one young life was already over. For her there would never again be parades, or music, or kisses, or flowers, or children, or love. Mary Phagan never left the National Pencil Company alive. Abused, beaten, and strangled by a rough cord pulled so tightly that it had embedded itself deeply in her girlish neck and made her tongue protrude more than an inch from her mouth, Mary Phagan lay dead, dumped in the dirt and shavings of the pencil company basement, her once-bright eyes now sightless and still as she lay before the gaping maw of the furnace where the factory trash was burned.”

* * *

IN 1913 GEORGIA, it was customary in criminal cases for all of the prosecution and defense witnesses to be sworn before any of their testimony was taken. In the hot and crowded temporary Fulton County courtroom at 10AM on July 28, 1913, Solicitor Hugh Dorsey called his witnesses and they were duly sworn. But the Leo Frank defense team, in the persons of Luther Rosser and Reuben Arnold, surprised everyone by asking to have their witnesses sworn at a later time, claiming that — though they had just declared themselves fully ready to go to trial — their witness list was as yet “fragmentary” and would occasion severe delays if it were required to be completed that morning. But presiding Judge Leonard Roan ruled against them, and in all of five minutes the defense was ready to call their list. It turns out that the defense had wanted to conceal for a time their strategy of making Frank’s character a factor in his defense, and revealing the names of their witnesses — numbers of prominent Atlanta Jews, Frank’s former Cornell University classmates, and others — made that strategy obvious, and would give the prosecution time to find rebuttal witnesses on the subject of the character of Leo Frank.

The first witness was Mrs. Fannie Coleman, Mary Phagan’s mother. She described her last moments with her daughter on the morning of the previous April 26. When asked to identify the clothes that 13-year-old Mary had worn that day, she broke down.

The next witness called was 15-year-old George Epps, who said he’s ridden on the trolley car with little Mary from 11:50AM to 12:07PM, when she’d disembarked to go see Superintendent Leo Frank at the National Pencil Company and pick up her pay. The exact timing of Mary’s visit to Frank was to become very important later in the case.

The third prosecution witness — Newt Lee, the pencil company’s night watchman and the man who found Mary Phagan’s bruised body in the factory basement in the wee hours of April 27 — was very damaging to Frank.

Lee stated that he had arrived at work early — at 4PM — on the day of the murder at the explicit instructions of Frank, who had said he was planning to attend a baseball game with a relative. But when Lee came to the factory at 4, Frank appeared very nervous and agitated and said that Lee should leave immediately and come back at 6. When Lee said he’d rather rest for a while at the factory building than go out, Frank insisted that he must go out for two hours.

When Lee did come back, Frank was still acting strangely and became extremely agitated when, around the same time, a friend of Mary Phagan’s and a former worker at the plant, J.M. Gantt, showed up and asked to retrieve some shoes he’d left on the premises. Frank was so nervous that he fumbled the routine task of putting Lee’s slip into the time clock, taking twice as long as usual. After Frank went home, he telephoned Lee to ask him if everything was “all right” — something that Lee said he had never done before.

Lee told the court that, the day after the murder, Frank had told authorities in his presence that Lee’s time slip for the previous night had been punched correctly:

“When did you see Frank?”

“I saw Mr. Frank Sunday morning at about 7:00 or 8:00. He was coming

in the office.”

“How did he look at you?”

“He looked down on the floor and never spoke to me. He dropped his

head down this way.”

“Was any examination made of the time clock?”

“Boots Rogers, Chief Lanford, Darley, Mr. Frank and I were there when

they opened the clock. Mr. Frank opened the clock and said the punches

were all right.”

“What did he mean by all right?”

“Meant that I hadn’t missed any punches.”

This was ominous testimony from Leo Frank’s point of view: As part of an apparent attempt to incriminate Newt Lee, Frank had later told police that Lee had missed several punches — implying that he had had time to be involved in the murder. Around the same time a bloody shirt was planted on Lee’s property. It was detected as a fake when the pattern of stains showed it had not been worn when stained, but had been crumpled up and wiped in blood.

Rosser’s cross-examination of Lee that day could not shake him in any element of his story.

* * *

The following is a direct transcription of part of the coverage of the first day of the trial in the Atlanta Constitution (July 29, 1913):

Watchman Tells of Finding Body of Mary Phagan

MOTHER AND THE WIFE

OF PRISONER CHEER HIM

BY PRESENCE AT TRIAL___

Jury Is Quickly Secured and

Mrs. Coleman, Mother of

the Murdered Girl, Is First

Witness to Take Stand.Dateline Atlanta, Georgia — July 28, 1913: With a swiftness which was gratifying to counsel for the defense, the solicitor general and a large crowd of interested spectators, the trial of Leo M. Frank, charged with the murder of Mary Phagan on April 26, in the building of the National Pencil factory, was gotten under way Monday.

When the hour of adjournment for the day had arrived, the jury had been selected and three witnesses had been examined. Newt Lee, the night watchman who discovered the dead body of Mary Phagan in the basement of the National Pencil factory, and who gave the first news of the crime to the police, was still on the stand, undergoing a rigid cross examination by Luther Z. Rosser, attorney for Frank.

Lee Sticks To First Story.

When the trial is resumed this morning, Newt Lee will again be placed on the stand. It Is not expected that anything new will be adduced from his testimony. Throughout the gruelling cross-examination of Mr. Rosser Monday afternoon Lee stuck to his original story in minutest detail.

Questions that would have confused or befuddled a man of education failed to budge him from the statement he originally made to the police, and has repeated from time to time to reporters and court officials.

The first day’s proceedings of the Frank trial proved singularly free of the dramatic element or the unexpected in testimony. There were touches of the pathetic, as, for example, when Mrs. J.W. Coleman, mother of the dead child, broke down and cried bitterly when she viewed the clothing of her little daughter; and there were touches of humor when the little Epps boy, who had ridden to town with Mary Phagan on the day of her murder, explained to Luther Rosser his method of telling the time of day by the sun, and of Newt Lee, who amused the courtroom by his quaint allusions and his negro descriptions of a tiny light in the basement of the pencil factory, which he likened to the gleam of a lightning bug, and of his quick retort when Mr. Rosser purposely spoke of this insect as a June bug.

“I didn’t say June bug—I said lightning bug,” contradicted Newt.

Careful Attention to Detail.

This brief excerpt Is given as significant of the careful attention to detail that Lee gave to his story.

When the hour of 9 o’clock arrived, Pryor Street in front of the temporary courthouse building was cluttered with the usual mob of the morbidly curious. They hugged the hot walls of the buildings like lethargic leeches, vainly trying to gain admission to the building, or buzzed about like bees, gossiping idly of the case.

Perfect order was maintained, however, and few not directly interested in the trial were allowed to enter the courtroom. All day long the crowd remained on the sidewalks gazing intently at the window to the courtroom, spewing tobacco juice on the street, eagerly questioning every person who left the building.

Interest naturally centered on the appearance in the court of Leo M. Frank, the accused. If Frank has chafed under his confinement, his physical appearance belies the fact. He looked as fit physically as he did the day he was first arrested. He was dressed with scrupulous neatness in a gray suit of pronounced pattern, which was all the more conspicuous on account of his diminutive form. As he entered the courtroom he smiled cordially at several friends. The first person to whom he spoke was a woman employee of the pencil factory.

Next in interest was Mrs. Leo M. Frank, wife of the accused, who, up to this time, has been seen little in public. Mrs. Frank is an extremely attractive-looking young woman. During progress of the trial she kept her eyes constantly fixed on Solicitor Dorsey. Her gaze was one of calm estimate. She seemed to be attempting to fathom his thoughts and to divine his purposes.

Mrs. Coleman Takes Stand.

Efforts to show Mary Phagan’s attitude toward Leo M. Frank by the state and efforts by the defense to show the dead girl’s attitude toward little George Epps, the 14-year-old newsie who testified to riding down town with her on the morning before she was found dead, were the first important things attempted yesterday when the trial of the state v. Leo M. Frank, charged with the Phagan girl’s murder on April 26, was formally opened.

Both efforts were promptly blocked for the present time by opposing counsel, and the testimony was started in regular form by the introduction of Mrs. J. W. Coleman, mother of Mary Phagan, as the first witness for the state.

During the preliminaries Attorneys Reuben R. Arnold and Luther Z. Rosser, for Frank, tried to conceal the names of their witnesses, but on Solicitor Hugh M. Dorsey’s objections, they were overruled by Trial Judge L.S.Roan, and they called and swore their witnesses as the state had done but a few moments previously.

In a come-back for this the defense asked the court to honor their duces tecum which they previously served upon the solicitor, requiring him to bring into court all statements and affidavits made by James Conley, the negro sweeper, who made an affidavit incriminating himself and declaring he had aided Frank in disposing of the girl’s body.

Solicitor Dorsey, after a conference with Frank A. Hooper, a brilliant criminal lawyer aiding him, dictated a statement to the court stenographer in which he agreed to produce these affidavits and statements at the proper time, should they be held material.

Defense Announces Ready.

The case started promptly at 9 o’clock, with the courtroom, thronged with veniremen and spectators, witnesses and lawyers and friends of the principal. Contrary to the persistent rumor that the defense would ask postponement and to their frequent objections to the trial in the heated term, the defense proved ready and willing to go to trial…

You can read the entire Atlanta Constitution for this day by downloading this PDF file. The complete Atlanta Georgian can be downloaded here, and the entire Atlanta Journal can be read by downloading this file.

* * *

Source: American Mercury