Today, March 11, 2016, is the 30th anniversary of the granting of a limited pardon to Leo Frank.

Today, March 11, 2016, is the 30th anniversary of the granting of a limited pardon to Leo Frank.

by John Pierson and Vanessa Neubauer

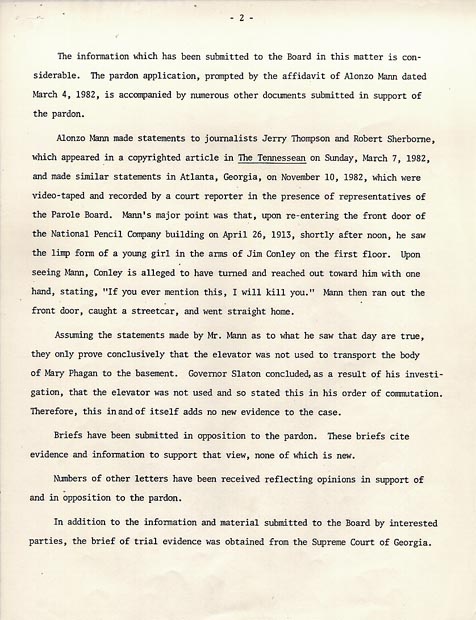

IN 1983 — 70 years after the conviction of sex killer and Atlanta B’nai B’rith president Leo Max Frank for the murder of Mary Phagan — lawyers associated with the Jewish Anti-Defamation League (ADL), the Atlanta Jewish Federation and the American Jewish Committee tried to obtain a pardon for Frank. (ILLUSTRATION: Leo Frank gives a big smile for the camera just two days after the murder of Mary Phagan. The snapshot was published the next day, April 29, 1913 on the cover of the Atlanta Journal. It was taken at a time when it was widely believed that a Black man, Newt Lee, would be charged with the crime.)

The ADL based their claims almost entirely on the 1982 affidavit of Frank’s office boy, Alonzo Mann, who took 69 years to reverse his trial testimony. Mann, elderly and with mounting medical bills, created a media sensation when he averred — contrary to what he had testified in 1913 — that he had seen another man (Frank’s janitor and accessory after the fact Jim Conley) carrying Mary Phagan’s body on the day of her murder.

Tremendous pressure was placed on the Georgia State Board of Pardons and Paroles to exonerate Frank and issue him a pardon. But the Jewish groups’ efforts failed. The Board ruled that Alonzo Mann’s new affidavit added nothing of substance to the evidence and did not at all, despite Mann’s opinion to the contrary, prove that Frank was innocent. It only proved that Conley may have carried Mary’s body by a different route than the one to which he had admitted in 1913. (Even the prosecution stated — as did Conley himself — that Conley had moved the body.) The pardon request was rejected and Frank’s conviction was affirmed and upheld.

So, in 1986, after some changes in the composition of the Board — and some changes in their own tactics — the ADL and its allies tried again. This time they argued for a pardon based not on Frank’s innocence, but instead on the much more limited claim that the state had failed to protect Frank from lynching and so had cut off the possibility of future appeals by which he might have attempted to prove his innocence. This time the Jewish groups were successful. The Board did issue a pardon for Leo Frank — but it was a curious pardon indeed, a pardon which specifically stated that it was in no way altering the guilty verdict which the jury had pronounced on Frank — a pardon that directly and firmly affirmed that it was a pardon without exoneration.

The Phagan family were consulted by the Board in the run-up to the 1983 pardon decision, since the surviving members of the family had a great deal of personal knowledge of and documentation about the case, and would be directly and profoundly affected by any decision. It was their Little Mary who had been strangled and likely raped, after all.

But in 1986, the Phagan family were not consulted. They were told about the upcoming pardon decision after the ADL and its well-heeled allies had been meeting with and lobbying the Board for six months or more. Except for the signatures at the bottom of the paper, it was a done deal. Why the secrecy? Obviously, the Jewish groups, led by the ADL — and whoever had decision-making power on the Board by then — didn’t want the victim’s family to have any say on the matter, nor any time to alert the public as to what was afoot.

Mary Phagan-Kean’s Report

The victim’s grand-niece, Mary Phagan-Kean, wrote one of the most even-handed books ever penned on the Frank case, The Murder of Little Mary Phagan, published in 1987. Though she and her family strongly believe that the jury’s verdict — and that of the appeals courts, including the Supreme Court of the United States — was correct and that Frank is guilty, her book is very fair in its presentation of the views of the ADL, other Jewish groups, and the pro-Frank forces generally. Here we can read her report of the 1983 and 1986 pardon efforts, excerpted from The Murder of Little Mary Phagan:

“I am not working for Leo Frank or his family,” [ADL lawyer] Dale Schwartz stated publicly. The core of seeking a pardon for Leo Frank, he said, was an attempt to obtain an official repudiation of anti-Semitism and bigotry and to “remove a blot on Georgia history.” As such, the petitioners based their case for pardon not on the legality of the trial and conviction of Leo Frank, but on extra-legal concerns.

The League, in a memo, compared the Frank case to the Holocaust:

I agree entirely that our constituency — the literate world — knows that Frank was railroaded. Our constituency also knows that the Holocaust was real, but we continue to counteract Holocaust denial. We have also proceeded on the assumption that it was important for the German nation to come to terms with the past and acknowledge the terrible crime committed in days gone by. Likewise some of us here in Atlanta think it is important that the State of Georgia acknowledge its sins in the Frank case, and repent.

To say in the 1980s that Leo Frank was innocent, attorney Edgar Neely argued, impugned not just the Georgia system of justice in 1913 but the reputation of its lawyers in general and particularly Frank’s counsel. Though apparently otherwise unconnected to the case, Neely submitted a formal brief opposing the pardon, which stated, in part:

I am speaking as an individual, steeped in the law, who wants the law to be upheld and the judicial system of Georgia not ex post facto impugned.

The leaders of the pardon effort responded at length, including the outlining of the “new evidence” of Alonzo Mann, pointing out that it had been unavailable to Frank’s lawyers. Mobley Howell, then Chairman of the Board of Pardons and Paroles, is said to have considered Neely’s arguments carefully.

… Dale Schwartz commented:

The public has come to understand the pardon process as an exoneration, particularly if it is coupled with a statement as to the innocence of the applicant.

He stated that a gubernatorial proclamation might appear as “one of hundreds of such proclamations and would not have the publicity impact that a pardon would.”

As Dale Schwartz told the editor of Israel Today in a 1984 interview, “It was determined that Georgia would perhaps recognize the type of posthumous pardon which did not merely grant ‘forgiveness’ for a crime committed in the past, but rather would ask the defendant to forgive the state for having wrongfully convicted him.”

So on February 14, 1983 my father and I responded with a letter to the Board [language of a Senate Resolution, also lobbied for by Jewish groups, that preceded the pardon is shown in italics — Ed.]:

Dear Mr. Moore and Board Members:

We would like to present our views concerning the Resolution adopted in the Senate on March 26, 1982:

WHEREAS, Leo Frank was tried in the Superior Court of Fulton County in 1913 for the murder of Mary Phagan and

This is a true statement.

WHEREAS, he was convicted in an atmosphere charged with prejudice and hysteria; and

This issue was decided by the Supreme Court of the United States. In Georgia Reports, Volume 141, Pages 246 & 247, Numbers 16-18, it states: “The alleged disorder in the courtroom during the progress of the trial was not of such character as to impugn the fairness of the trial, or furnish sufficient ground for reversing the judgment refusing a new trial. On conflicting evidence the judge on the hearing of the motion for new trial, acting as trior, did not err in holding the jurors whose impartiality was attacked were competent.”

WHEREAS, he was sentenced to death but his sentence was commuted by Governor John Marshall Slaton; and Governor Slaton stated: “It will thus be observed that if commutation is granted, the verdict of the jury is not attacked, but the penalty is imposed for murder, which is provided by the State and which the Judge, except for his misconception, would have imposed. Without attacking the jury, or any of the courts, I would be carrying out the will of the Judge himself in making the penalty that which he would have made it and which he desires it shall be made.”

WHEREAS, in August of 1915, he was taken by a mob from the state institution in Milledgevile and carried to Cobb County where he was lynched; and

This is true.

WHEREAS, Alonzo Mann, a fourteen-year-old witness at the Frank trial, was threatened with death and was not asked specific questions which could have cleared Frank; and Frank was ably represented by a counsel of conspicuous ability and experience — Luther Rosser, Reuben Arnold, and Herbert and Leonard Haas. They knew what they were doing.

WHEREAS, Mr. Mann has come forward to clear his conscience before his death and claims that Leo Frank did not commit the murder of Mary Phagan; and Alonzo Mann gave an opinion that was sworn to, he did not submit any evidence contrary to the conviction of Leo M. Frank. How long did he work at the Pencil Factory? I believe his testimony stated two Saturdays. We challenge and doubt his claim.

WHEREAS, if Leo Frank was not guilty of such crime, it is only fitting and proper that his name be cleared, even after his death.

Leo M. Frank was convicted in a court of law by his peers and was duly sentenced to death.

NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED BY THE SENATE that this body strongly requests that the State Board of Pardons and Paroles conduct an investigation into the Leo Frank case; and, if the evidence indicates that Leo Frank was not guilty, the Board should give serious consideration to granting a pardon to Leo Frank posthumously.

Over the past seventy years, no real new evidence has been submitted. On March 10, 1982, Mr. Mobley Howell stated: “His innocence would have to be completely proven with complete evidence.” This case will never be put to rest. Every three to five years, somebody reintroduces the case to the public.

As Phagan family members, we hereby request a copy of the applicant’s application and any evidence submitted. We also request any information regarding requests for the Leo M. Frank/Mary Phagan case in the future.

… Dale Schwartz said that the petition contained three hundred pages of evidence. The major pieces were “an affidavit from Alonzo Mann, who was Frank’s office boy at the time of the murder, and a two-and-one-half-hour videotape of Mann giving that affidavit in which he asserts Frank’s innocence.” [Why, we ask, has this video evidence not been made public? — Ed.]

Among those who exhorted the Board to pardon Leo Frank were a minister in Tennessee who felt that pardon would “bring a sense of reassurance to many of our citizens who have been hurt and still suffer because of the prejudicial trial to which he was subjected many years ago,” and a member of the Christian Council of Metropolitan Atlanta, who viewed a pardon as a way to “repudiate the twin evils of prejudice and mob rule.”

I think most of the Phagan family felt as I did about this latest episode: we had known about the application for the posthumous pardon beforehand, and while we weren’t pleased with the Board’s considering the application, we realized there was more here than just interest in clearing the name of Leo Frank.

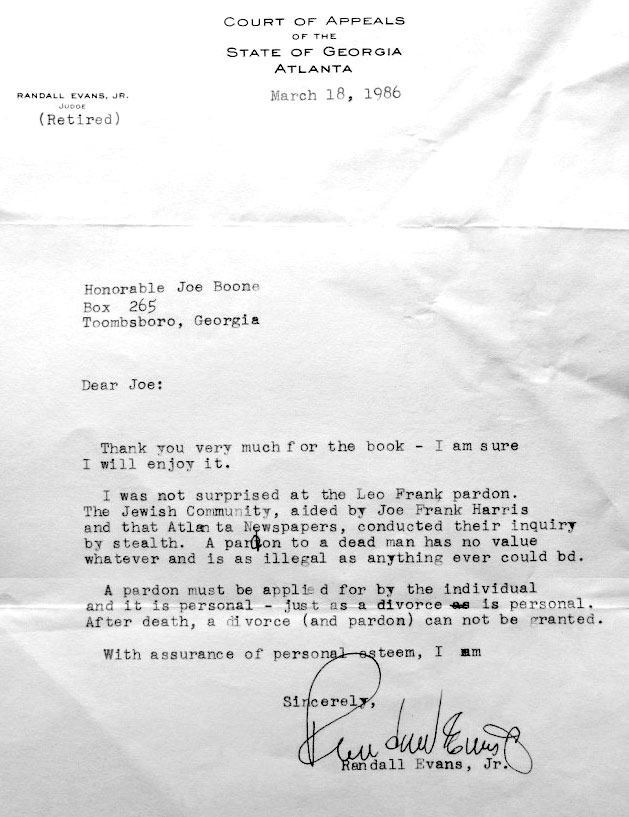

Part of a statement by Judge Randall Evans Jr.:

The Constitution of Georgia provides that “the legislative, judicial, and executive powers shall forever remain separate and distinct.” The executive department has no power whatever to reverse, change, or wipe out a decision by the courts, albeit while the prisoner is in life he may be pardoned. But a deceased party can not be a party to legal proceedings (Eubank v. Barber, 115 Ga. App. 217-18). If Leo Frank were still in life, he could apply for pardon, but after death neither he nor any other person may apply for him.

Mary Phagan-Kean again (The Murder of Little Mary Phagan):

When I received the information that I requested, I learned that the application for pardon filed was indeed illegal. Why, then, had it been accepted? There were only two instances in which a pardon could be granted. According to the rules of the Pardons and Paroles Board:

1. A pardon may be granted to a person who, to the Board’s satisfaction, proves his innocence of the crime for which he was convicted under Georgia law. Newly available evidence proving the person’s complete justification or non-guilt may be the basis for granting a pardon. Application may be submitted in any written form any time after conviction.

2. A pardon which does not imply innocence may be granted to an applicant convicted under Georgia law who has completed his full sentence obligation, including serving any probated sentence and paying any court-ordered payment, and who has thereafter completed five years without any criminal involvement. The five-year waiting period after sentence completion may be waived if the waiting period is shown to be detrimental to the applicant’s livelihood by delaying his qualifying for employment in his chosen profession. Application must be made by the ex-offender on a form available from the Board on request.

On August 9 I contacted Edgar Neely. I wanted to know why he opposed the pardon. He told me that the April 26 article made his blood boil. He personally knew Reuben Arnold and Hugh M. Dorsey and felt it was a disgrace to discredit these fine lawyers. He had even argued cases against Reuben Arnold, and felt he was brilliant. He stated that the evidence is “flimsy because no one is alive to dispute Alonzo Mann,” and that he wanted to uphold the courts, “as Leo Frank got a fair trial for that time.” Therefore, he had written a letter to the Board stating his opposition.

On September 27, 1983 they permitted my father and me to address the Board. Sitting on the Board were Mobley Howell, Chairman, Mamie Reese, member, James Morris, member, Michael Wing, member, and Wayne Snow, Jr., member. They had not realized that the Phagan family existed until Mike Wing informed them. They had become concerned about our feelings and felt that we could share them with the whole Board. They were responsive and understanding [when] my father addressed the Board.

The Board had begun work on the pardon in January 1983, pretty much going over the same routes of investigation that John Slaton had sixty-eight years earlier.

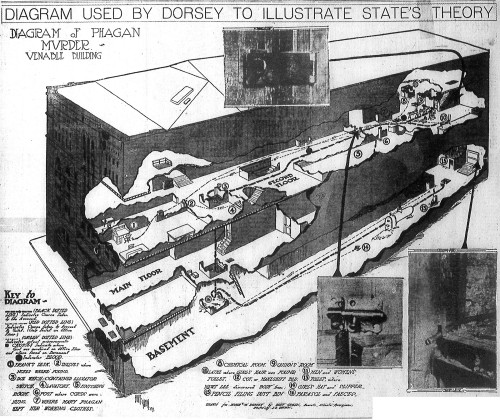

It organized an investigation staff under the direction of Chairman Silas Moore. This staff was presented with “evidence”: newspaper accounts, the trial brief, books, and letters — along with short summaries. Many of the Board members turned to history books to get a perspective on the lynchings, yellow journalism, and the general temper of the time when little Mary Phagan had been murdered.

Alonzo Mann’s testimony was the first to be evaluated. While many, including Mr. Mann, felt that his new recollection “proved” Frank’s innocence, the Board felt it merely cast doubt on Jim Conley’s testimony. It proved in the Board’s estimate that Jim Conley lied about carrying Mary Phagan in the elevator, and possibly about her dying on the metal room floor, but it did not prove that Frank had not killed her upstairs nor even that he might not have later killed her downstairs. The Board felt Mann made Conley into a liar, which everyone knew, but not necessarily a killer. Also, the seventy-year gap that made his testimony so sensational to the media and would-be movie producers cast doubt on the validity of his recollections. Moreover, it was perceived that his testimony itself had internal contradictions.

Once the Mann evidence had been weighed and found to be non-conclusive, there wasn’t much to go on. “We set about to do almost the impossible,” one Board member was to state publicly, “to reconstruct something that occurred seventy years ago — frankly, all the actors were deceased except Alonzo Mann. We were totally at the mercy of accounts by others — mostly journalism accounts, letters — and mostly opinions.” He was correct: no other witnesses appeared; no one unearthed heretofore secret material; and, despite rumors, there was no concrete evidence of a confession by Jim Conley. Seventy years after it all began, the Leo Frank case remained a mystery — and, because of the passage of time, an even deeper mystery. Even if Alonzo Mann’s account were entirely true, Frank still could have killed Mary Phagan, either accidentally or deliberately, either in combination with Jim Conley or on his own — or he could have been completely innocent.

And, while the pardon effort was motivated by extra-legal goals, it spoke of the pardon process as within the structure of the “judicial process” that provided for “the privilege of pardon and commutation as a ‘safety valve’ for use in extraordinary cases,” and probably worked against it. As if meant for a formal court, the application cited federal court cases to justify “standing” to seek a pardon. The petitioners, in attempting to repudiate anti-Semitism, represented their attempt as a legal effort to repudiate the libel against the Atlanta Jewish Community — an “injury in fact.”

The conclusion of the pardon application read:

The public good will be served; a historic injustice will be corrected; a seventy-year libel against the Jewish Community of Georgia will finally be set aside, and the soul of Leo Frank will, at last, rest in peace.

Mary Phagan-Kean on the 1986 Pardon

[In March 1986 m]y father and I met with Wayne Snow, Jr., the new chairman of the Board, and Mike Wing. We were told that the Jewish community had again filed application for a posthumous pardon. And that if a pardon were issued, it would be based not on guilt or innocence but on the contention that “the State did not protect Leo Frank and that his rights were violated.” The Board felt that the lynching of Leo Frank was wrong. And that this pardon would “heal old wounds.”

Apparently, renewed efforts for pardon had begun in September 1985. And while at first the petitioners had thought they’d failed to obtain the pardon in 1983 simply because they had not brought enough pressure to bear, they had come to see that, beyond the strictly procedural action of the process which sought to establish Leo Frank’s innocence or Jim Conley’s — or someone else’s — guilt, what was most probably achievable was a pardon that addressed the extra-legal case about Leo Frank.

And this approach by the petitioners allowed Board members’ sympathies for the extra-legal aspects of the case to come through. The Board had been deeply concerned about the problem of setting a precedent for a huge number of posthumous pardon applications, were Frank pardoned on strictly legal bases. By addressing the extra-legal case, however, the precedent that a pardon would grant would only be to exceptional cases like the Frank case. So, six months prior to the Board’s contacting me, an initial proposed pardon application made its way through to some members of the Board. This initial draft repudiated the old standard of absolute innocence and made no mention of a pardon based on innocence or guilt. By March, members of the Board had agreed in principle to grant a special type of pardon which would imply neither innocence or guilt, but merely address the concerns brought about by the case. They approved such a pardon in early March.

After meeting with representatives of the petitioners, the Board began drafting a final pardon order which they approved shortly after ADL officials and others found it acceptable.

But our family had questions.

Why was there no public announcement of receipt of application?

Why were other people who opposed granting of the pardon not told of the new application?

Former Chairman Silas Moore announced the issuance of a pardon order on March 11, 1986 at 1:00 P.M. at the Georgia State Capitol.

It seems that Board members had finally agreed on the bases for granting a pardon. They reflected concern that Frank’s lynching had foreclosed efforts to prove him innocent. The Board also addressed three extra-legal concerns — the repudiation of lynch law, the need to heal old wounds, and the acknowledgement of anti-Semitism.

The question of whether Leo Frank had really committed the murder — the search for his purity or demonhood — was now just dust in the wind. In the discussions of pardon from September through March 1986 the Board had done no detective work, except to ensure the accuracy of its final order, discussing the historic background to the Frank trial. The Board simply overlooked guilt or innocence, something it had never done in pardons of forgiveness or pardons of innocence.

The reports had indicated that the Board worked in secret with the Jewish community for almost a year and Wayne Snow, Chairman of the Board, stated this publicly during a TV station interview. This disturbed us. Wayne Snow had told us at the beginning of March that the Board was thinking of granting a pardon, but, in fact, had already made the decision which they announced immediately after they spoke to us.

We wondered what the purpose was of keeping it secret?

The pardon was covered by the media across the country. Everyone who knew me sent me the articles. Most of the newspapers reported that the relatives of Mary Phagan said that “Frank’s official pardon doesn’t mean he was innocent.”

The Board’s Statement

“Without attempting to address the question of guilt or innocence and in recognition of the state’s failure to protect the person of Leo M. Frank and thereby preserve his opportunity for continued legal appeal of his conviction, and in recognition of the state’s failure to bring his killers to justice,” the board hereby grants Frank a pardon.…

The lynching, according to the board, “resulted from the State of Georgia’s failure to protect Frank.” It then failed to “prosecute any other (sic) lynchers,” thus “compounding the injustice” done Frank.

In 2015, around the 100th anniversary of Leo Frank’s lynching, a rabbi named Steve Lebow had paid to have a billboard erected in the Atlanta area stating “Leo Frank is innocent” as a part of his pressure on Georgia political leaders to issue an explicit exoneration of Frank, including a number of high-profile media events. Mary Phagan-Kean’s reaction was strong and to the point (Marietta Daily Journal):

Among those who likely won’t be attending any of those events is retiree Mary Phagan Kean of Ellijay, the grand-niece and namesake of “Little Mary” Phagan. Kean has served as her family’s spokesperson in recent decades, giving voice to the many here who still think Frank was guilty.

His 1986 pardon was the result of political pressure and threatened economic pressure, she says.

“That’s why they granted it,” Kean said. “They could not prove that Leo Frank was not guilty. (That ruling) was bought and paid for by the supporters of Leo Frank. That rabbi (Lebow) needs to stop all this cr-p. It’s already been decided. He has no clue what he does to our family when he brings this up.”

Alonzo Mann and His “New Evidence”

Clearly, without the decades-late affidavit of Alonzo Mann, neither of the pardon petitions would have been able to gain any traction at all. The massive evidence against Frank in the Brief of Evidence, and the decisions of the Coroner’s Jury, the Grand Jury, the trial jury, and every court of possible appeal all spoke with one voice: Leo Frank was guilty, and no TV miniseries, polemic book, or media hysteria could change that. But Alonzo Mann managed to do what the multi-million-dollar decades-long Jewish publicity campaign had failed to do.

But how much reliance can we place in Mann’s affidavit? According to the editors of the Leo Frank Case Research Library:

What really happened in 1913? First, let’s look at Mann’s testimony at trial in 1913, from the Official Brief of Evidence:

Alonzo Mann: I am office boy at the National Pencil Company. I began working there [Tuesday] April 1, 1913. I sit sometimes in the outer office and stand around in the outer hall. I left the factory at half past eleven on April 26th. When I left there, Miss Hall, the stenographer from Montag’s, was in the office with Mr. Frank. Mr. Frank told me to phone to Mr. Schiff and tell him to come down. I telephoned him, but the girl answered the phone and said he hadn’t got up yet. I telephoned once. I worked there two Saturday afternoons of the weeks previous to the murder and stayed there until half past three or four. Frank was always working during that time. I never saw him bring any women into the factory and drink with them. I have never seen Dalton there. On April 26th, I saw Holloway, Irby, McCrary and Darley at the factory. I didn’t see Quinn. I don’t remember seeing Corinthia Hall, Mrs. Freeman, Mrs. White, Graham, Tillander, or Wade Campbell, I left there 11:30 [AM].

CROSS EXAMINATION:

When Mr. Frank came that morning, he went right on into the office, and was at work there and stayed there. He went out once. Don’t know how long he stayed out.

In 1982, Alonzo Mann changed his story and alleged that he really left the National Pencil Company factory at noon, instead of 11:30 am (as he had testified in 1913). He then went on to say that at 12:05 — five minutes after he left the factory — he came back and saw the 27-year old African-American janitor, Jim Conley, carrying the limp body of Mary Phagan on his shoulder, positioned as if getting ready to dump her down the two-foot-by-two-foot scuttle hole next to the elevator. Jim Conley then allegedly reached out for Alonzo Mann and said to the young boy, “if you tell anyone I will kill you.” Alonzo Mann claimed that he ran home and told his family, and alleges that his parents then told him not to tell anyone or get involved.

Alonzo Mann’s affidavit became the basis of an attempt to obtain a “posthumous pardon with exoneration” for Leo Frank from the Georgia State Board of Pardons and Paroles. The effort was led by Charles Wittenstein, southern counsel for the Anti-Defamation League, and Dale Schwartz, an Atlanta [Jewish] lawyer [also associated with the ADL].

The Jewish community — and the media — present the pardon at face value as a vindication of Leo Frank. But consider another view: In order to pardon someone of a crime, that person has to be guilty — you can’t pardon someone unless you first acknowledge his guilt. Therefore, the guilt of the individual has to be affirmed — and in Leo Frank’s case it was affirmed again and again, at every level of the appellate system. All, including the State Board of Pardons and Paroles, preserved his verdict of guilt.

The Board members were patently in error when they alleged that the lynching prevented Frank from making any further appeals within the appellate court system, because Leo M. Frank had fully and totally exhausted all of his court appeal options at every level of the State, District, and Federal Appellate Courts, with the Supreme Court unanimously overruling any further review of the case, thus closing the door forever at all levels of the appellate court system. When there were no more options left in the court system, the State Board of 100 years ago refused a recommendation of clemency — and even the likely-bribed Governor John M. Slaton, refused to pardon Leo Frank and actually stated in his commutation letter he was not disturbing the guilty verdict. Not a single legal body in the last century has overturned the guilty verdict of Leo Frank, but attempts to spin the truth have endlessly been made.

Refuting Mann’s Claims:

In 1982 Alonzo Mann was in the twilight of his life, frail, and in terrible physical condition. Mann was perched on a cane and had a pacemaker, was on a cocktail of pharmaceuticals — and truly lonely. The WWI veteran had, sadly, outlived his wife and only son. His virtual “death-bed” revelation in the years before he died had all the flair of a fictionalized Hollywood or Broadway drama — and the markings of another backroom bribery deal, which has been the central strategy of Leo Frank’s defenders for a century. The Georgia Supreme Court records containing Leo Frank’s appeals reveal the birth of this ugly strategy.

First: Why would white parents in the white racial separatist Atlanta, Georgia of 1913, tell their son not to tell the police about a murdering and guilty black janitor — especially when the result of not telling the police would ultimately result in an innocent, clean cut, and white boss, Leo Frank — a man who gave their son a highly prized job — going to the gallows? In the Old South, African-Americans were seen as prone to violent outbursts and were regarded as third class citizens with child-like mental and emotional maturity; and they were often not afforded the same legal protections as whites when accused of crime — and were usually easily convicted.

Second: Why would these white parents, in a white separatist South, allow their son to report back to work on Monday morning, April 28, 1913 — two days after that son was threatened with death by a black man carrying a dead white girl on his shoulder, knowing that that same black man would be there too? Jim Conley reported back to work that Monday, April 28, 1913, as did the 170 other employees, who were naturally expected to be back at work after the holiday weekend. Jim Conley was not arrested until Thursday, May 1st, 1913.

Third: If Alonzo Mann admitted to lying under oath at the Leo Frank trial in 1913 — “withholding information” and saying he left at 11:30 am instead of noon as he contended 69 years later — who’s not to say he wasn’t lying again in 1982 and beyond?

Fourth: If Alonzo Mann walked in on Jim Conley at 12:05 PM while Conley was getting ready to throw Mary Phagan’s body down the scuttle hole, why did Monteen Stover — who testified she came down the stairs near the front entrance and scuttle hole at exactly that time — not witness this scene also? Why didn’t Leo Frank — who was just 40 feet away — not hear Mary Phagan scream or any sounds of a struggle at all?

Fifth: If Alonzo Mann or his parents kept quiet because they were afraid of retribution from Jim Conley, why did they not tell the authorities what Alonzo had seen once Jim Conley was arrested? Conley was arrested on May 1, 1913, convicted of being an accessory after the fact in the murder of Mary Phagan, and remained imprisoned throughout the entire year of 1914.

Sixth: If Alonzo Mann was “terrified” into silence by Jim Conley, why did that terror not end in 1962, when Conley is reported to have died?

Wouldn’t there have been forensic evidence on the body of a 4’11” 107-pound girl if she had fallen 14 feet? Mary Phagan had numerous autopsies performed on her by doctors in late April and early May of 1913, and none of the reports mention any broken bones or indications on her body that she had fallen 14 feet to a hard dirt floor. In fact the forensic evidence shows that the scratches on her face caused by her being dragged 150 feet across the basement floor — from the elevator to the rear of the cellar — had no blood coming from them, indicating she was already quite dead when she reached the basement.

The autopsy reports revealed Mary had died of strangulation and the black eye suggested a left-handed man had punched her in the face. What percentage of people are left-handed? According to Wikipedia.org, “A variety of studies suggest that 70–90% of the world population is right-handed.” (Wikipedia, “Lefthandedness,” 2013). Since Leo Frank was left-handed and Jim Conley right-handed, who was more likely to have punched her in the right eye with a left fist?

And none of the defense theories give us any explanation at all of the hair which, along with dried blood, was found on the lathe in the metal room upstairs, nor for the blood stains found nearby on the metal room floor.

If Alonzo Mann was indeed telling the truth about Jim Conley sitting near the factory entrance all morning long doing nothing on the morning of the murder, it definitely suggests that Leo Frank might have lied to the court when he gave his unsworn statement to the jury: Frank said he did not even know Jim Conley was in the factory at all on the day of the murder. (Leo Frank Trial Statement, Brief of Evidence, August 18, 1913)

How could Leo Frank not know Jim Conley was there, when Leo Frank admitted at the trial that during the morning he left the building and came back after running morning errands, including a brief trip to Sigmund Montag’s office down the block to get the mail? (Leo Frank, Brief of Evidence, August 18, 1913). How could Leo Frank miss seeing someone sitting next to the staircase he would have traversed at least twice, coming and going?

Where Jim Conley sat on the first floor was no more than 30 to 40 feet from where Leo Frank sat in his inner office on the second floor. And the first floor lobby of the National Pencil Company was the highest traffic point in the entire building: It was where people would come and go all day long during the work week, and all morning long on Saturdays.

On Saturday, April 26, 1913, people were coming to collect their pay envelopes and several employees were present in the morning for a half-day’s work. Leo Frank was on the second floor, in his office, on April 26, 1913, as he was on most Saturdays. He surely could have heard a scream from 30 to 40 feet away, had there been one. Jim Conley, in fact, claimed he heard a scream after Leo and Mary went to the metal room, a considerably greater distance than Frank’s office. Leo Frank did not mention a scream at all.

If Jim Conley had attacked Mary Phagan in the lobby, Leo Frank would almost certainly have heard a scream directly below him. He could then have easily called the police, as the telephone was inside Frank’s office on the wall. (See Defense diagrams of the second floor).

The theory of Jim Conley beating, robbing, and “possibly raping” a white girl in the place where Monteen Stover would likely have walked in on him doing it, would almost surely guarantee Monteen’s backing up into a street filled with white men — and then, for Jim Conley, a castration without anesthesia, or worse, would ensue. This is how men of color accused of raping white girls were generally treated in 1913 Atlanta — that is, just before they were lynched from a tree or riddled with bullets. Imagine how it would have fared for one such not merely accused — but caught in the act!

Alonzo Mann never mentioned seeing Tillander, Corrie, or Emma — thus sustaining his original statement he left the Factory at 11:30 AM on April 26, 1913 — not the supposed noon he claimed 69 years later. Another interesting statement at trial was that of Hattie Hall, Frank’s stenographer: She did not mention seeing Alonzo Mann when she left at noon, supporting therefore the idea that Alonzo Mann did leave the factory at 11:30 and not at noon.

Alonzo Mann claimed he came back to the factory at 12:05 pm — almost immediately after supposedly leaving at noon — because he wanted to speak to Herbert George Schiff. But evidence suggests that Schiff was never expected to be at work on this holiday and, in fact, he never showed up — a fact which no one disputes. This casts further doubt on Alonzo Mann’s story about coming back and seeing Conley in the act of carrying Mary Phagan’s body.

Frank gave several different times for Mary Phagan’s arrival at his office: 1) “12:02 to 12:03” (The time he gave police orally on Sunday, April 27, 1913); “12:05 to 12:10, maybe 12:07” (The time he gave in a deposition to police on Monday, April 28, 1913 known as State’s Exhibit B, 1913); then it became “12:10 to 12:15” (The time he gave at the Coroner’s Inquest, May 5 and 8th, 1913); and finally “12:12 PM to 12:17 PM.” (Leo Frank Trial, August 18, 1913).

These ever-latening time claims damaged Frank’s credibility beyond repair, and, to make matters worse, all of these times were during a time period he could not account for, even with Lemmie Quinn’s “boxing him in” at 12:20. One thing is obvious: If Frank’s later time claims are regarded as true, then Alonzo Mann’s 1982 affidavit is false. They are mutually exclusive.

The editors at the Leo Frank Case Research Library aren’t the only ones who find Mann’s affidavit very questionable. Writer and researcher Lawson Wellborn provides one of the best analyses of the document:

The Phagan family conducted a full and complete interview in 1934 with Jim Conley, the star witness of the State against Leo Frank. Conley was also the man the Frank defenders settled on as the most likely murderer instead of Leo Frank. The Phagan relatives’ interview with Conley convinced them that Conley was telling the truth about Mary’s murder. Mary Phagan Kean wrote “[t]here is no way my father would have let Jim Conley live if he believed that he had murdered little Mary.”

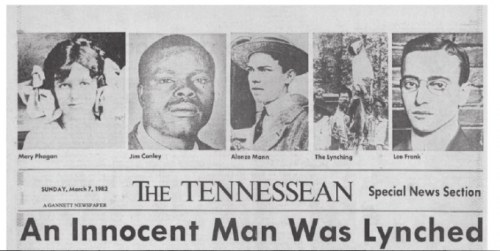

Thus it came as something of a shock to the general public that in 1982 newspaper attention suddenly focused on the elderly Alonzo Mann. Mr. Mann was about the same age as Mary Phagan at the time of her death and had testified as a defense witness for Frank in his capacity as Frank’s office boy at the murder trial. Now Mann emerged from the shadows with the startling revelation that he had actually seen Conley carrying the apparently lifeless body of Mary Phagan down the front staircase when he re-entered the Pencil Factory on April 26, 1913. Jerry Thompson, Nashville Tennessean veteran reporter and anti-Klan investigator, worked up Mann’s story and brought it before the public.

Mann was given lie detector tests and passed them. “Lie detectors” are not admissible in court in Georgia — unless all parties agree. They are of limited effectiveness because pathological liars and the very best of con artists often pass while persons of a more nervous disposition fail — even when the latter are telling the truth.

The Georgia Courts have mocked “lie detector” tests as follows:

There is simply no “lie detector,” machine or human. The first recorded lie detector test was in ancient India where a suspect was required to enter a darkened room and touch the tail of a donkey. If the donkey brayed when his tail was touched the suspect was declared guilty, otherwise he was released. Modern science has substituted a metal electronic box for the donkey but the results remain just as haphazard and inconclusive.

On the national level the United States Supreme Court ruled in 1998 in United States v. Scheffer, that courts could bar the admission of the results of polygraph examinations in all cases without violating an accused’s constitutional rights. The Court did so because it noted that there is no consensus in the scientific community on the reliability of the “lie detector.” In short, the highest court in the land holds the “lie detector” to be “junk science.”

Mann’s ability to pass such a questionable test at best implies that he either completely believed his story or was an excellent story teller.

The Nashville Tennessean article was a tremendous hit; it was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and picked up by newspapers all over the nation. On television and radio programs commentators gleefully announced that Mann’s testimony erased all doubts — baseless though they might have been — that Frank was actually innocent of the murder of Mary Phagan. As the Tennessean’s headline for the special supplement of March 7, 1982 shouted: “AN INNOCENT MAN WAS LYNCHED.” Books, docudramas and prizes for investigative journalism rained down on the heads of the crusading scribblers.

Mann’s story was significant in that it directly contradicted Conley’s testimony of how Conley got the body of Mary Phagan to the basement of the factory after the killing. As the reader may recall, Conley was definitive in his testimony that he used the elevator to transport the corpse. The elevator had always interested the Frank partisans and Mann emerged as the last living witness to the case to discuss this exact issue.

The affidavit executed by Mann may be summarized as follows:

He was called as a witness for Frank, but he did not then reveal to any lawyer about his knowledge contained in the affidavit. Now, he was coming forward after the lapse of seventy years. “I want the public to understand that Leo Frank did not kill Mary Phagan.” He blamed his parents, his speech impediment and his fear of the crowds outside the trial “yelling things like ‘Kill the Jew!’” for his reluctance to speak up. Mann stated he was too young at the tender age of 14 to have realized that if he told what he saw that Frank would have been found innocent.

Here is what Mann claimed he saw the day Mary Phagan died. When Mann arrived at the factory at 8:00 a.m, Conley was seated under the stairwell of the first floor of the Pencil Factory. Conley had already consumed a lot of beer. Mann ignored Conley’s request for money and went up the stairway to assume his duties as Frank’s office boy. Frank arrived shortly afterwards. Mann worked till before noon when Frank permitted him to leave to join his mother for the Confederate Memorial Day parade. Mann promised Frank he would return after the parade and Frank allowed that he would probably still be at the Pencil Factory.

Leaving shortly before noon, Mann had not seen Mary Phagan come to collect her pay. Conley was still lounging in the stairwell when Mann left the factory. Mann did not pinpoint his departure time. He states he could have left between 11:30 or 11:45.

He stated “[I]t could not have been more [emphasis added] than a half hour before I got back to the pencil factory.” In other words, Mann returned somewhere between 12:00 and 12:15 based on his statement. Mann entered by the front door again, and looking to his right, saw Conley with Mary Phagan’s limp body (although he didn’t know Mary’s name at the time) standing between a trap door that led to the basement and the elevator shaft. He observed no blood or wound on the body of this limp, short white girl dressed in “pretty, clean clothes.” Mann was of the impression that Conley was about to dump the body down the trapdoor. He could not recall if the elevator was on the first floor; if it was not, then the shaft would have been open as well. “…[I]n a voice that was low but threatening and frightening to me he [Conley] said: ‘If you ever mention this I’ll kill you.’”

Mann started up the stairs to the second floor. He thought he heard movements up there, but thought better of it, turned and fled out the front door. Conley reached out for him, but Mann “raced away from the building.” Arriving at home, he told his mother — whom he was to have met at the parade — what he had seen. She immediately advised him never to tell a soul. “She told me that I was never, never to tell anybody else what I had seen that day at the factory. She said that she didn’t want me involved, or the family involved, in any way. She told me to go on about my business as if nothing had happened and that sometime soon I would have to quit working there. From then on, whenever I was at work, I steered clear of Jim Conley. I kept away from him and he did the same.”

“When my father came home my mother explained to him what I had seen and what Conley had said to me. My father told me to forget it and never mention it.”

Later, when questioned by detectives, Mann never told them about his return to the Pencil Factory building. At Leo Frank’s trial, while testifying as a witness for Frank, Mann only answered the questions he was asked. He was following the advice of his mother and father and did not volunteer any further information. Mann offered his opinion that Conley was after Mary’s pay; he was not planning a sexual assault. [Mann’s ability to read Conley’s mind is quite extraordinary. — Ed.]

“Many times I have thought since all this occurred almost seventy years ago that if I had hollered or yelled for help when I ran into Conley with the girl in his arms that day I might have saved her life. I might have. On the other hand, I might have lost my own life. If I had told what I saw that day I might saved Leo Frank’s life. I didn’t realize it at the time. I was too young to understand.”

Family members continued to tell Mann not to tell anyone his story for years afterwards. An Atlanta newspaperman unnamed by Mann (but said by others to have been Ralph McGill, another crusading, Pulitzer Prize-winning liberal journalist) was disinterested in his story.

Mann also contradicted the testimony of the female factory employees who accused Frank of bringing women into the factory for immoral purposes. Mann never witnessed any such conduct. (Mann did not mention that he began working for Frank on April 1, 1913 so he had only been at the factory for twenty-six days at the time of murder.)

The Mann affidavit reopened the drive of the Jewish community for a “posthumous pardon” for Leo Frank. At a press conference at the Atlanta Jewish Community Center on April 1, 1982, the drumbeat began again. Jerry Thompson, at the press conference, was asked about the Phagan family’s reactions to all this information. “Jerry Thompson stated that some Phagan family members upheld their belief in the convicted Leo Frank’s guilt while others ‘were trying to be objective.’” “Sherry Frank (no relation to Leo Frank), area director of the American Jewish Committee, said Jewish leaders would like to make a possible exoneration of Frank an issue in the gubernatorial race this year.”

Alonzo Mann, possibly because of his age and infirm heart, refused to respond to any questions except through his handlers at the Nashville Tennessean. This author contacted the Tennessean and was so informed at the time the news broke. Mary Phagan-Kean was given the same answer, but because of her family connections she was finally able to meet Mr. Mann and form some impressions about him. She thought him “a fine gentleman; he believed what he had seen to be evidence of the truth.”

Since Mann was never subjected to any cross-examination nor, evidently, even tough questioning about these matters, we are left with three possibilities concerning the worth of his testimony on an historical basis. It has long been held in Anglo-Saxon law that trial by affidavit is worthless and the cross-examination of a witness is essential to establish the truth or falsity of a proposition. So while Alonzo Mann’s affidavit is valueless from a legal standpoint, it does have historical significance and must be so analyzed as we find it.

Mann’s recollections could be (1) completely accurate and factual; or (2) weakened by seventy years of guilt and blurred memories, but basically accurate; or (3) a complete fabrication drawn up either by himself or with the assistance of other parties for a number of plausible reasons.

Since Mann cannot be examined, having answered to the highest tribunal on March 19, 1985, let us look more closely at the statement itself.

First of all, Mann states that mobs were shouting things like “Kill the Jew” outside the trial. The most careful writers on the subject all agree that this is an urban myth with no basis in fact. Steve Oney, the most recent author on the subject, points out that there is no contemporary evidence for such a statement. Governor Slaton in his commutation order denied that Frank had been tried by a mob. But, like the typical urban myth, the legend persists. It is probably propelled by later events after the Slaton commutation and the assault of the “Knights of Mary Phagan” on the State Prison in Milledgeville.

In the statement Mann put himself as leaving the factory between 11:30 and 11:45. In his trial testimony, as recorded in the brief of evidence, Mann testified twice that he departed at 11:30. Since his testimony was given closer in time to the event in issue, we may presume that at least he was inaccurate in the later affidavit as to the time of his departure unless he was fudging on that topic when testifying for Frank at trial. So Mann’s affidavit is clearly at variance in this important matter with his own trial testimony given relatively shortly after the event. Given the heavy emphasis the defense attached to the timing of the assault on Mary, this is significant to say the least. It would seem highly unlikely that the skilled interrogation by Frank’s attorneys failed to unearth the later departure time (to say nothing of Mann’s return to the factory) given their theory of the case turned on the time element so heavily.

It is also noteworthy because of the importance attached to the timing of the arrival of Mary at the Pencil Factory. The defense made much of the testimony of streetcar operators that Mary could not have possibly arrived at the factory prior to 12:12 p.m. Although Dorsey seriously damaged this theory in his cross-examination, the defense steadfastly held to this narrative. If Mann’s recollections are correct, then pressing his affidavit times to the furthest, most favorable limit for Frank, the latest Mann could arrive back at the factory on the fatal day is 12:15 p.m. Under Mann’s time constraints, Mary had to be able to ascend the staircase, obtain her pay envelope from Frank, ask about work on Monday and descend the staircase, be attacked by Conley either upstairs or downstairs (without Frank hearing any struggle or screams in the otherwise quiet factory, as it was a holiday) be lifted up and carried by Conley to the point where he was seen by Mann next to the “hole” and elevator shaft. All this had to occur within an absolute maximum of three minutes. If Mann’s statement that he was away from the factory for not more than one-half hour is true, then in order to get Mary to the factory after Monteen Stover testified she arrived, Mann’s departure time had to change.

Stover’s unimpeached testimony is that she was in Frank’s outer office from 12:05 until 12:10 by the clock on the wall in the office. Frank was absent from his office and not a sound was heard by Stover. Consequently, the defense always asserted that Mary arrived two minutes after Monteen left — just enough time for the two of them to miss each other on the staircase and the street outside the factory. If Mann was gone for no more than thirty minutes, then his departure time must be shifted forward from his trial testimony or else he returns before Mary, by Frank’s testimony and the elaborate defense calculations, could have even arrived at the factory. No Frank defender has offered any explanation for the new time problems created for the defense by Mann’s affidavit.

Consider the plausibility of the affidavit statements concerning the response of Mann’s parents to the news that their son had witnessed what was doubtless the most sensational murder of their lifetimes. Conley returned to work on Monday, April 28th after the murder. Mann evidently returned to work as well according to his affidavit. Conley would continue to report to work until his arrest on May 1.

Can we believe that a fourteen year old lad would report to work alongside a black man who he had every reason to believe had committed the murder of Mary Phagan? Mann would have permitted an innocent man, the black night watchman Newt Lee, to languish in the jail while the sweeper Jim Conley, whom he feared — now with better reason than ever before — looked malignantly at him each day. Is that believable — even in present day America?

Gentle reader, life in 1913 Atlanta was considerably rougher. Keep in mind what Mann asked us to believe. Once he eluded Conley’s outstretched hand, he was on the sidewalk outside the factory. The streets of Atlanta were teeming with crowds attending the Confederate Memorial Day parade. If he raised his voice to call for help, a crowd would have quickly responded. The life expectancy for Mr. Jim Conley would have been very short if a crowd of 1913 whites found a black man holding the limp (and possibly dead) body of an adolescent white girl in that time and in that place. Yet Mann didn’t know what to do; he didn’t alert any policeman he may have chanced to meet nor the trolley crewmen on his way home. He didn’t speak to anyone till he got home. He raced straight home where his missing mother had already arrived. His parents, certainly not made of stern stuff, advised silence. Even after Frank was arrested the Mann clan remained mum.

The most amazing part of the affidavit is Mann’s statement that his loving parents, worried about the family getting involved in all this, still advised him to return to work where he would be in close proximity to the purported murderer, Jim Conley. Did it never occur to any of them that Conley could just as easily have silenced the only witness to see him with the girl’s body? Why advise their beloved son to return to the zone of danger and yet remain silent?

But suppose all of this was true. The Manns thought Conley so dangerous to Alonzo’s safety that they remained silent and let their son go back to work with a homicidal maniac. Once Conley was in police custody that problem was resolved. What was more, a reward was offered for evidence leading to the conviction of the murderer. Did the Manns have no interest in talking about a murderer now in police custody with the additional attraction of a cash reward?

Conley is thought to have died about 1962. Why didn’t Mann come forward then? Surely he didn’t fear the powers of Conley to do him harm extended beyond the grave.

Finally, we come to Conley, “the Prince of Darktown.” To listen to the Frank defenders recite their narrative, Conley was a criminal mastermind who was able to outwit and frame poor Leo Frank and thereafter to withstand the pounding and intense cross-examination of the finest criminal defense attorneys in Georgia of their day. All the time, the criminal mastermind was well-aware that a white boy of fourteen had seen him with the body! Under these circumstances, would Conley have shown up at the National Pencil factory on the Monday after the murder insouciant and confident? Clearly, Conley appeared because he believed he was safe and protected from whatever role he had in this homicide. If Mann saw him on the first floor landing and Conley knew it, why would he loiter at the plant until he was arrested on May 1? Reason and experience with criminal defendants dictates that had the incident occurred as Mann related, Conley would had caught the first freight train headed out of Atlanta and “rode the rods” to any distant geographical point to escape the accusing finger of Mann and the pursuing lynch mob. If Conley did choose to remain in town, wouldn’t he have taken more effective steps to silence a witness than simply warning Mann to shut up?

Furthermore, why would the Moriarty criminal mastermind of Conley not incorporate the Mann incident into his statement and confession to the police? If Conley’s confession was concocted, why would he go to the trouble of inventing the tale of the elevator knowing that Mann stood able to give him the lie? He could have even used Mann to bolster his story by claiming that he carried Mary’s body down the steps at Frank’s direction and dropped it down the trapdoor. Furthermore, Mann could verify that story! “Bring in the office boy and question him!” Conley could have challenged Mann and turned an uncertainty into supporting evidence.

Conley, though, stuck to his version of how the body was transported to the elevator and never volunteered that Mann was a possible witness.

Conley was bringing Mary down the stairs. Where had they been? Why had Frank heard nothing if the assault took place virtually in his office? Additionally, the condition of Mary Phagan’s body when found was quite different than described by Mann. This can only be accurate if Mary was unconscious and then revived when Conley got her to the basement. When Mary’s body was found it was filthy, her dress was torn and she was so blackened by soot and dirt that some of the police could not tell what race she was. (Which could lead to a third explanation for her death. That explanation, unexamined by all the Frank apologists, is that Frank assaulted Mary in the metal room. She was knocked against a machine and fell unconscious. Frank thought her dead and summoned Conley. Conley then finished the job after she came to in the basement. Before dying, Mary apparently put up a real struggle. This explains some of the irregularities in both Frank’s and Conley’s stories. But the preference is to depict Frank as a martyr, a real mensch. This alternative doesn’t please the Frank community. Frank would still be a murderer under the law of almost every state in the union and in 1913 would have gotten the death penalty.)

One member of the Pardons and Parole Board considering Mann’s affidavit pointed out that Mann dropped out of school to work against his parents’ wishes. “Why would a man who wouldn’t obey his parents about school,” [Michael] Wing wondered, “obey them when it came to potentially letting an innocent man hang?”

Furthermore, Mann showed no concern that day about Leo Frank, a man for whom he expressed respect in later years. Frank, after all, should have still been in the building when Mann returned to find Conley toting a dead girl in his arms. Mann stated he thought he heard movement upstairs. He evidently never considered the fact that Frank — whom he believed to be in his office upstairs — or anyone else still in the factory could have been in peril even decades later when reviewing the case.

And we have the issue of the defense attorneys and police investigators. Evidently, none of them were able to pierce the veil Mann and his family cast about his covert knowledge. This young lad was able to fool even trained investigators who were desperately trying to either free their client or uncover the real story. The defense attorneys interviewed him and decided to use Mann as a witness for Leo Frank. Nevertheless, this naive lad of 14, who had no idea that his information could save an innocent man’s life and who quaked in terror of the now incarcerated Conley, never gave his secret away.

Given the huge problems with the 1982 Mann statement on its face, it is impossible to believe that Mann told the truth in that document. All human experience runs directly contrary to the behavior he attributes to almost every participant in his affidavit.

The Phagan case was cursed from the very beginning with people volunteering “tips” and “clues.” It appears most likely that Alonzo Mann was merely the last of many to offer a fanciful solution to the case.

Since his solution was superficially suited to the Frank defenders’ longstanding press campaign to exonerate Frank, it has received fabulous coverage. Many articles and news statements flatly assert that it closes the case entirely.

As helpful as the Mann statement appeared to be at first blush to the Frank defenders, it does have a major defect; it merely disputes Conley’s testimony about how the body was transported to the place it was found. It does not establish whether Conley or Frank was the murderer. After all, Frank was still upstairs when Mann says Conley was carrying the body from that location. What was Frank doing upstairs when Mary Phagan was attacked?

Thus because of these shortcomings and infelicities in Mann’s statement, the document was not of sufficient gravitas or credibility outside of press newsrooms to create the expected popular groundswell which would impel the Georgia Board of Pardons and Paroles to issue a pardon or other exoneration of Frank from culpability in the murder of Mary Phagan.

But the shortcomings outlined above did not give serious pause to the Frank camp.

Because it disputed the Conley testimony, it was immediately ballyhooed, without close consideration, as a complete exoneration of Leo Frank.

It does no such thing.

Dinnerstein and the “Anti-Semitic” and “Hang the Jew” Hoaxes

One of the main reasons cited by the ADL lawyers in seeking a pardon for Frank was to rebuke and disavow the Southern “anti-Semitism” which they see as the main reason for Frank’s arrest and conviction. The American Mercury‘s Elliot Dashfield writing in “The Leo Frank Case: A Pseudo-History” states that Jewish academic Leonard Dinnerstein, who has virtually made a career out of writing about Frank, is the real source of the claims that homicidal anti-Jewish mobs intimidated the jury in the Frank case:

In his article in the American Jewish Archive Journal (1968) Volume 20, Number 2, Dinnerstein makes his now-famous claim that mobs of anti-Semitic Southerners, outside the courtroom where Frank was on trial, were shouting into the open windows “Crack the Jew’s neck!” and “Lynch him!” and that members of the crowd were making open death threats against the jury, saying that the jurors would be lynched if they didn’t vote to hang “the damn sheeny.”

But not one of the three major Atlanta newspapers, who had teams of journalists documenting feint-by-feint all the events in the courtroom, large and small, and who also had teams of reporters with the crowds outside, ever reported these alleged vociferous death threats. And certainly such a newsworthy event could not be ignored by highly competitive newsmen eager to sell papers and advance their careers. Do you actually believe that the reporters who gave us such meticulously detailed accounts of this Trial of the Century, even writing about the seating arrangements in the courtroom, the songs sung outside the building by folk singers, and the changeover of court stenographers in relays, would leave out all mention or notice of a murderous mob making death threats to the jury? During the two years of Leo Frank’s appeals, none of these alleged anti-Semitic death threats were ever reported by Frank’s own defense team. There is not a word of them in the 3,000 pages of official Leo Frank trial and appeal records — and all this despite the fact that Reuben Arnold made the claim during his closing arguments that Leo Frank was tried only because he was a Jew.

… In his book, Dinnerstein completely fails to mention the well-known strategy of Leo Frank’s defense team to play on the racial conflicts present in 1913 Georgia and pin the murder of Mary Phagan on, successively, two different African-American men.

The first victim was Newt Lee, the National Pencil Company’s night watchman. After that intrigue fell apart, Frank’s team abruptly changed course and tried to implicate the firm’s janitor — and, according to his own testimony, Frank’s accomplice-after-the-fact — James “Jim” Conley. Leo Frank’s defense team played every white racist card they could muster against Jim Conley at the trial, and continued doing so through two years of appeals. Frank’s own lawyer, addressing the jury, said “Who is Conley? Who was Conley as he used to be and as you have seen him? He was a dirty, filthy, black, drunken, lying nigger…Who was it that made this dirty nigger come up here looking so slick? Why didn’t they let you see him as he was?” Had this been said at trial by anyone other than Leo Frank’s defense attorney, it would have been thoroughly denounced by any academic with even half the normal quota of flaming outrage against white racism. But as for Dinnerstein…. Well, with only 40 years to study the case, I suppose he just overlooked it.

As stated by Bradford L. Huie of the American Mercury, the claim of widespread hatred of Jews in the Old South is preposterously false:

Far from being a region rife with hatred for Jews, the South in general and Atlanta in particular were regarded by Jews as a haven and as a place nearly free from the anti-Semitism they suffered in other parts of the nation and the world. Even today, and even after Jewish-gentile relations there were strained by the Frank case and by Jewish support for the civil rights revolution, the Christians who form most of the population of the South are stoutly pro-Jewish. The South is the center of Christian Zionism and American support for the Jewish state of Israel.

Can a Dead Man be Pardoned?

As reported by radio host and investigator Carolyn Yeager, on May 15, 1983, retired Georgia Appeals Court Judge Randall Evans Jr. published a statement on the Leo Frank case in The Augusta Chronicle-Herald in which he claimed that the proposed posthumous pardon of Frank was “completely ridiculous” because a dead man can’t be pardoned. Evans also said that the evidence of Frank’s guilt “was overwhelming” and described the commutation of Frank’s sentence as “the rape of the judicial process” by Govenor Slaton. Evans had also commented on the successful 1986 ADL pardon effort, writing in a letter shortly after the pardon was granted:

I was not surprised at the Leo Frank pardon. The Jewish community, aided by Joe Frank Harris and the Atlanta newspapers, conducted their inquiry by stealth. A pardon to a dead man has no value whatever and is as illegal as anything ever could be. A pardon must be applied for by the individual and it is personal — just as a divorce is personal. After death, a divorce (and pardon) cannot be granted.

Signed Randall Evans Jr.

[There was once an] attempt by some fans of O. Henry, the short-story writer, to get a pardon for their hero, who was convicted in 1898 of embezzling $784.08 from the bank where he was employed. But you cannot give a pardon to a dead man. A pardon can only be given to someone who can accept it.

Back in 1830 George Wilson was convicted of robbing the U.S. Mail and was sentenced to be hanged. President Andrew Jackson issued a pardon for Wilson, but he refused to accept it. The matter went to Chief Justice [John] Marshall, who concluded that Wilson would have to be executed. “A pardon is a slip of paper,” wrote Marshall, “the value of which is determined by the acceptance of the person to be pardoned. If it is refused, it is no pardon. George Wilson must be hanged.”

The clear meaning here from the Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court is that the person to be pardoned must first request a pardon, and then personally accept it. This follows that a pardon cannot be given to a dead man who not only has not personally asked for it, but who cannot accept or decline it.

For we must remember, it is generally assumed that acceptance of a pardon is an implicit acknowledgment of guilt, for one cannot be pardoned unless one has committed an offense. That is the reason a pardon might be rejected.

The ADL’s Wild Claims

The Jewish ADL has made many claims, both echoing Dinnerstein and inventing some of their own, in support of their efforts to exonerate Frank and obtain a pardon for him. Some of their claims are quite reckless and insupportable.

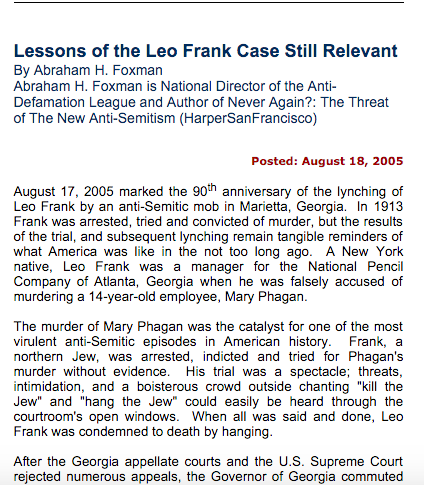

In 2005, ADL boss Abraham Foxman made the bizarre and insupportable claim that Frank was “convicted without evidence”:

The murder of Mary Phagan was the catalyst for one of the most virulent anti-Semitic episodes in American history. Frank, a northern Jew, was arrested, indicted and tried for Phagan’s murder without evidence. His trial was a spectacle; threats, intimidation, and a boisterous crowd outside chanting “kill the Jew” and “hang the Jew” could easily be heard through the courtroom’s open windows. When all was said and done, Leo Frank was condemned to death by hanging.

Leo Frank partisans have hinted repeatedly at a supposed “confession” of Jim Conley to the murder of Mary Phagan, but no documented confession has ever been found. In 1934, according to the Phagan family, Conley was interviewed at length and convinced the Phagans that he did not kill Mary Phagan and that his trial testimony was truthful, which seems a very unlikely thing for him to do had he confessed to the murder many years earlier. Furthermore, it is difficult to believe that no legal body would have taken any interest whatever in such a confession — and none did — especially considering the high profile of the case and the well-funded nationwide crusade to exonerate Frank. Even the man who is perhaps the most respected proponents of Leo Frank’s innocence, the author Steve Oney, considers the confession to be an urban legend. Oney and his staff made a years-long diligent search for a Conley confession, and found nothing.

But that didn’t stop ADL lawyer Dale Schwartz, one of the leaders of the pardon drives, from making one of the most bizarre claims in the whole Frank affair. According to Mary Phagan-Kean in her book The Murder of Little Mary Phagan, Schwartz not only claimed that Conley had confessed to the murder, but had done so “thousands of times,” asserting that these thousands of confessions “should, standing by themselves, warrant the granting of the posthumous pardon.”

And on that note, we leave the decision as to who is more credible — Dale Schwartz, Rabbi Lebow, Abraham Foxman, Leonard Dinnerstein, and their posthumous-pardon-seeking ilk — or the jury who convicted Leo Frank after hearing all the evidence from both sides — to you, dear reader, and to history.

* * *

Source: Authors