Another in our series of new transcriptions of contemporary articles on the Leo Frank case.

Atlanta Constitution

Thursday, May 1st 1913

Mary Phagan Was Growing Afraid of Advances Made to Her by Superintendent of the Factory, George W. Epps, 15 Years Old, Tells the Coroner’s Jury.

BOY HAD ENGAGEMENT TO MEET HER SATURDAY BUT SHE DID NOT COME

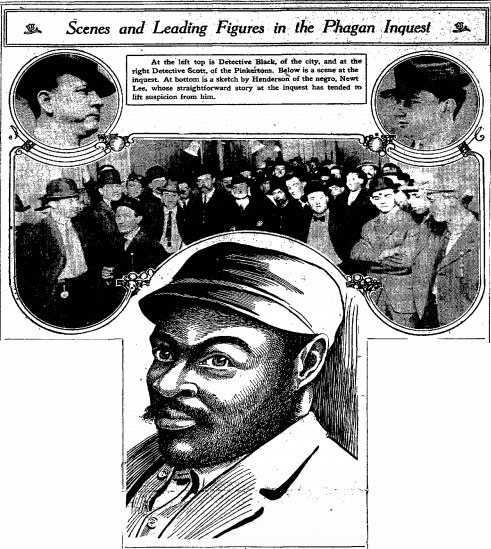

Newt Lee, Night Watchman, on Stand Declared Frank Was Much Excited on Saturday Afternoon—Pearl Robinson Testifies for Arthur Mullinax—Two Mechanics Brought by Detectives to the Inquest.

LEO FRANK REFUSES TO DISCUSS EVIDENCE

When a Constitution reporter saw Leo M. Frank early this morning and told him of the testimony to the effect that he had annoyed Mary Phagan by an attempted flirtation, the prisoner said that he had not heard of this accusation before, but that he did not want to talk. He would neither affirm nor deny the negro’s accusation that never before the night of the tragedy had Frank phoned to inquire if all was well at the factory, as he did on the night of the killing.

Evidence that Leo M. Frank, superintendent of the pencil factory in which the lifeless body of Mary Phagan was found, had tried to flirt with her, and that she was growing afraid of his advances, was submitted to the coroner’s jury at the inquest yesterday afternoon, a short time before adjournment was taken until 4:30 o’clock today by George W. Epps, aged 15, a chum of the murdered victim.

George rode with Mary to the city Saturday morning an hour before she disappeared at noon. He testified late Wednesday afternoon that the girl had told him of attempts Leo Frank had made to flirt with her, and of apparent advances in which he was daily growing bolder.

“She said she was getting afraid,” he told at the inquest. “She wanted me to come to the factory every afternoon in the future and escort her home. She didn’t like the way Frank was acting toward her.”

Waited Two Hours For Girl.

George had an engagement to meet the girl Saturday afternoon at 2 o’clock, he said. They were scheduled to watch the Memorial parade and tour the picture shows. He waited two hours for her. She had disappeared. The next known of her was when the lifeless form was found in the factory basement.

Frank was not present during the investigation but once. Detectives brought him before the jury for identification by E. S. Skipper, the man who saw the mysterious sextette of youths and girls Saturday night at Whitehall and Trinity. He remained but a moment.

Sensational developments were predicted shortly after the inquest was resumed at 2:15 o’clock, when Coroner Donehoo ordered detectives to bring to police headquarters the two mechanics who were in the factory building with Frank during the early part of Saturday afternoon.

They are Harry Denham and Arthur White, two youths who have been connected with the plant for several years. Detective Scott found them at work in the factory and escorted them to the inquest. They left the police station immediately after being examined.

A mystifying phase was added to the progress of the inquest when Edgar L. Sentell, a clerk in Kamper’s grocery, declared positively that he had seen Mary Phagan with Arthur Mullinax at midnight Saturday as they crossed the corner of Hunter and Forsyth streets a few yards distant from the pencil factory.

Sentell had known the dead girl since early childhood. They were intimate friends, he said. Asserting that he had spoken to her, he stoutly maintained that she had answered his greeting.

J. L. Watkins, a neighbor to the home to which Mary lived, also testified that he had seen her Saturday afternoon when she crossed Ashby street at Bellwood. She presumably was on her way home, he stated.

George Epps is a bright, quick-witted chap and proved an eager witness. He was brought before the inquest following the examination of Pearl Robinson, the sweetheart of Arthur Mullinax, who testified in that youth’s behalf.

“How old are you son?” was the first question asked him.

“Fifteen—going on sixteen,” he answered with alacrity.

“Do you work or go to school?”

“I work at a furniture store. In the afternoon I sell papers.”

His answers were clear and brief. He made a pleasing impression.

Lives Near Phagan Girl.

“How far do you live from 136 Lindsay street—the home of Mary Phagan?”

“Just around the block.”

“Did you know Mary?”

“Yes, sir, I certainly did. We were good friends.”

“When did you last see her alive?”

“Saturday morning, just before dinner when we came to town together on a street car.

“Did you arrange to meet her that afternoon?”

“Yes, sir. We were to have met at 2 o’clock in Elkin & Watson’s drug store at Five Points. We were going to see the parade and go to the moving picture shows.”

“How long did you wait for her when she failed to show up?”

“Until 4 o’clock in the afternoon. I stuck around two hours waiting for her. Then I had to go and sell my papers.”

“Did you inquire for her?”

“Yes. I went to her house when I got through with my papers. She hadn’t got back. The folks were looking for her.”

“When you and Mary were riding to town, did you talk any?”

She Wanted Money Mighty Bad.

“We talked a whole lot. She said she was going to the pencil factory to draw the wages due her. She said she didn’t have but $1.60 coming to her, but wanted that mighty bad.”

“How was she dressed?”

“She had on a blue dress and a dark blue hat. I remember that hat mighty well because I asked her why didn’t she buy a stylish lid? ‘Umph,’ she said, ‘I’m no stylish girl. I don’t need one.’”

“Did you both get on the car at the same time?”

“No. She was on first. When I got on she motioned for me to come and sit beside her. While we were coming to town she began talking about Mr. Frank. When she would leave the factory on some afternoons she said Frank would rush out in front of her and try to flirt with her as she passed.

She told me that he had often winked at her and tried to pay her attention. He would look hard and straight at her she said and then would smile. She called him Mr. Frank. It happened often she said.”

“How was the subject of Mr. Frank brought up?”

“She told me she wanted me to come down to the factory when she got off as often as I could to escort her home and kinder protect her.”

“When did you hear she was killed?”

“Sunday.”

Positive that he had seen Mary Phagan at midnight Saturday, Edgar L. Sentell offered to swear that it was the pretty victim whom he encountered with the suspected Mullinax at Forsyth and Hunter streets. He was the first witness during the afternoon session.

“I met Mary Phagan and Mullinax at Hunter and South Forsyth streets either between 11:30 and 12, or a little later. I am not positive which,” he stated.

“Were they standing together?” he was questioned.

“No. They were walking along.”

“Are you confident you knew both Mullinax and Mary?”

“I knew Mullinax at the car barns. I had known Mary all my life. I was born and raised with her.”

“When was the last time you saw her?”

“One week previous to Saturday night.”

“Did you speak to her?”

“I did. I said, ‘Hello, Mary.’”

“Did she reply?”

“She did. She said, ‘Hello, Edgar.’”

“Were her parents accustomed to letting her go with boys?”

Amazed to See Her Uptown.

“No. They were not. It amazed me when I saw her uptown at such an hour with a man. She looked like she was tired and fagged out.”

“What did she wear?”

“A light purple dress, black shoes and a light blue ribbon tied in her hair. She didn’t have a hat. An umbrella was in her hand.”

“Can you swear that it was Mary Phagan you saw?”

“I can and I will. I am swearing now that it was Mary Phagan I saw.”

“Can you swear it was Mullinax?”

“I am not so positive about him. If it wasn’t, it was his spit-and-image.”

“Did you know Mullinax’s name?”

“No. Not at that time. I had seen him so much around the car barns, though. I learned his name later.”

“When did you first hear of Mary’s murder?”

“Sunday morning on an English avenue trolley car.”

“Who did you first tell?”

“Mrs. Coleman, her mother.”

“Did the paper tell who was killed?”

Went to Mother Of Girl.

“No. I heard men at the car barn say the girl’s name was Phagan. I immediately remembered seeing Mary at midnight. I went straight to Mrs. Coleman and learned that it was her daughter.”

“Where did you work before becoming connected with your present employers?”

“I was in the navy.”

“When did you leave?”

“April 18, 1913.”

“How long had you been there?”

“Three months.”

“Why did you leave?”

“Because of eye affliction. I couldn’t read the targets on the rifle range.”

“Is your eye sight ordinarily affected?”

“Not particularly so.”

“Are you sure your eyes didn’t fail you when you saw this girl Saturday at midnight?”

“I am positive they did not.”

“Do you drink?”

“Occasionally. But I never get drunk.”

“Were you drinking Saturday night?”

“Not a drop.”

At this juncture the clothing worn by the murdered girl was held to the questioned man’s gaze.

“Is this the dress she wore when you saw her Saturday night?”

“It is.”

Bloody Hairs Are Found.

The discovery of a dozen strands of bloody hair identified by her sister workers as that of the murdered girls was related by R. P. Barrett, a mechanic in the pencil plant who made the find.

He was placed upon the stand directly after it had been vacated by Policeman Lasseter.

“What is your employment?”

“I am a machinist with the National Pencil company.”

“How long have you been with them?”

“Seven weeks.”

“Did you know Mary Phagan?”

“Yes. She ran a nulling machine at the factory.

“When did you see her last?”

“Tuesday, one week ago. She didn’t work after that because of shortage of metal.”

“How far is her machine from the dressing room she used?”

“About six feet.”

“Was anything unusual found around the machine at which she worked?”

Splotches Of Blood.

“The girls at the factory told me Monday that Mary had been murdered. They were dim, and looked as the floor at the base of her machine. I found several dim, and looked as though whitewash had been spread over them. It looked as though the floor had been swept carefully.”

“Was anything else found on the floor?”

“Yes. Monday morning, I started to work upon a lathing machine nearby the nulling machine of Mary’s. My hands became tangled with long hair. I picked out a dozen strands or more. They were bloody. A number of the girls came and identified them as having come from Mary’s head.”

“Was Mary a quiet girl?”

“Exceptionally quiet, and a very well behaved one.”

“Did anyone pay, or attempt to pay, attention to her?”

“Not of my knowledge. No one did around the factory.”

“How large was the spot of blood you found near the machine at which she worked?”

“About six inches in diameter. There several smaller spots.”

“What floor?”

“Second.”

“How near the elevator?”

“At the extreme end—200 or more feet, I would judge, from the lift.”

Girls Afraid Of Frank.

“Did you ever know of familiarity which Frank tried with Mary?”

“No.”

Declaring that, in his opinion, both of the notes found beside the dead girl’s body were written by the same person, F. M. Berry, assistant cashier of the Fourth National bank, and a handwriting expert, said that the script in the mysterious missives resembled only slightly that of the writing of the suspected watchman.

He took the stand at 3:30 p. m.

“What experience have you in distinguishing handwriting?”

“Only the experience that could be gained by my twenty-three years of service with the bank.”

The notes were shown him. He inspected them closely in the light of a window fronting Decatur street.

“Were they written by the same person?” he was asked.

“In my opinion, they were.”

Was Factory Used For Assignation?

Berry, the factory mechanic, was recalled to the stand at 4:10 o’clock. Sensational evidence was gained from him relative to the usage of the factory building as an alleged place of assignation for men and women.

“Did anybody work in the plant during a Saturday?” was the first question.

“No one of my direct knowledge. I heard, however, of two young employees who were at work on the top floor.”

“Do you know them?”

“Not their names.”

“Could you point them out to the detectives?”

“I could.”

“Then,” from Coroner Donehoo, “I will send a man after them. You go with him.”

“What is the usual pay hour of the factory?”

“At 12 noon on Saturdays.”

“Have you ever heard of the building used for immoral purposes?”

“Yes. Frequently. A Mr. Asbury Calloway, connected with the Scaboard offices near the factory building, has told me that he has often seen men and women and girls going in and out of the building at night.”

“Had you heard such rumors from the inside of the concern—by that is meant from attaches to the plant?”

“No.”

“Don’t you suspect that some of the girls of the factory have filled clandestine appointments in the building?”

“I don’t think so. I believe every girl in the place is straight—absolutely.”

Gantt Smiles During Quiz.

J. M. Gantt, the Marietta youth who is held as a suspect in the Phagan case, was put through a grueling examination. He never flinched through the ordeal, answered the questions promptly and concisely and smiled during the entire procedure.

He was put on the rack the moment his sweetheart, Pearl Robinson [Pearl Robinson was actually the sweetheart of Arthur Mullinax, not Gantt — Ed.], had been excused. He remained under examination probably longer than any other witness except the negro, Newt Lee. The time was an hour.

“Did you know Mary Phagan?”

“I did. I had known her since she was a little tot.”

“Were you ever employed with the pencil factory?”

“I was—up until three weeks ago.”

“Why did you leave them?”

“I was discharged.”

“Why were you discharged?”

Alleged Shortage the Trouble.

“Because of personal differences with Mr. Frank, the superintendent.

“What were the differences?”

“Two dollars short in the pay roll.”

“Were you in charge of the pay roll?”

“I was paymaster.”

“Did you ever see Frank with Mary Phagan?”

“No.”

“You always paid off the employees, did you not?”

“I did.”

“How were they paid?”

“With the envelope method.”

“Did you ever pay Mary Phagan?”

“Yes.”

“What did she make?”

“Presumably $4.05 a week, judging by the wage scale of the plant.”

“When did you see her last?”

“The day I quit the pencil company.”

“Had you seen her since?”

“No.”

“Where did you go on Saturday?”

Went to the Factory.

“I went to the pencil factory about 6:30 o’clock that afternoon.”

“Did you see Mr. Frank there?”

“Yes.”

“Did he appear excited, agitated?”

“Yes. He seemed nervous.”

“Did you ever hear Mary Phagan say she couldn’t trust Frank—that she feared him in any manner?”

“No.”

“How long were you in the building Saturday afternoon?”

“No longer than ten minutes.”

“What did you do?”

“I got a pair of shoes I had left in the place when I quit. Also, I telephoned my sister, Mrs. F. C. Terrell what time I intended coming home that night. I used the phone in Mr. Frank’s office.”

“Then what did you do?”

“Went to the poolroom, watched several games of pool and went home.”

“What time did you arrive home?”

“10:30 p. m.”

“Were you there when the police came?”

“No.”

“Did your sister tell of their visit?”

“No.”

Shank Takes Stand.

Other testimony relative to the rumored immoral reputation of the factory building was gained from V. F. Shank, of Shank Bros., whose establishment is on Forsyth street, near the pencil plant.

Shank was called immediately after Barrett had left the stand.

“Do you work at night?”

“I do.”

“Have you ever seen couples going into the pencil factory?”

“I have seen no couples. I have witnessed girls and men going singly into the place after dark.”

“How long has it been since you’ve seen this?”

“Last summer some time.”

“Did you make a statement recently of having seen girls enter the building?”

“I said a crowd of such sights I had seen. We were discussing the question of whether or not frolics were secretly held in the place.”

Thought Girl Was Mary.

E. S. Skipper, of 224 1-2 Peters street, testified that he saw a sextet of men and women reeling drunkenly up Trinity avenue from Whitehall street Saturday night shortly before 11 o’clock. One of the girls, he said, answered the description of Mary Phagan.

“What did you see at Trinity and Whitehall?”

“Three men, two women and a girl dressed like and resembling the dead girl whom I saw at Bloomfield’s. The girl was weeping and trying to break away from the party. She was being led up the street.”

“Did either man answer the description of Frank?”

“I haven’t seen Frank.”

At this juncture the examination was stopped. Frank was brought down from the detectives quarters and put face to face with the witness.

“That’s not the man,” Skipper said.

“When you saw these drunken men and women leading a reluctant girl, didn’t you think it your duty to call the police?”

“I see scenes like that on the streets every Saturday night.”

Step-Father Tells of Grief.

J. W. Coleman, step-father of the murdered girl, told graphically of the grief in the little home on Lindsay street over the death when he took the stand at dusk.

“How old was Mary Phagan?”

“She would have been 14 next June.”

“When did you last see her alive?”

“Friday night. She was at home early and was helping her mother with the housework. I left for work too early to see her Saturday morning.”

“When you got home Saturday afternoon, was Mary there?”

“No. My wife came and said ‘Mary has not come home. What do you suppose is the trouble? I am scared to death.’ I couldn’t eat supper. Her absence affected me. Mary was never known to be away from home at night.

I came to town and visited all the picture shows staying until they all had closed. When I returned, my wife and I speculated on what could have become of the child. We never slept any that night. At daybreak Helen Ferguson, a girl chum of Mary’s came over.

The moment she rang the door bell my wife jumped from her seat. ‘Oh Lord, that’s bad news from Mary,’ she said. The Ferguson girl came in. ‘Mary has been murdered,’ she told us. My wife fainted and she has been almost unable to walk since.”

The coroner then adjourned the inquest until 4:30 o’ clock today.

* * *

Atlanta Constitution, May 1st 1913, “Frank Tried to Flirt With the Murdered Girl Says Her Boy Chum,” Leo Frank case newspaper article series (Original PDF)