Another in our series of new transcriptions of contemporary articles on the Leo Frank case.

Atlanta Constitution

Sunday, May 4th, 1913

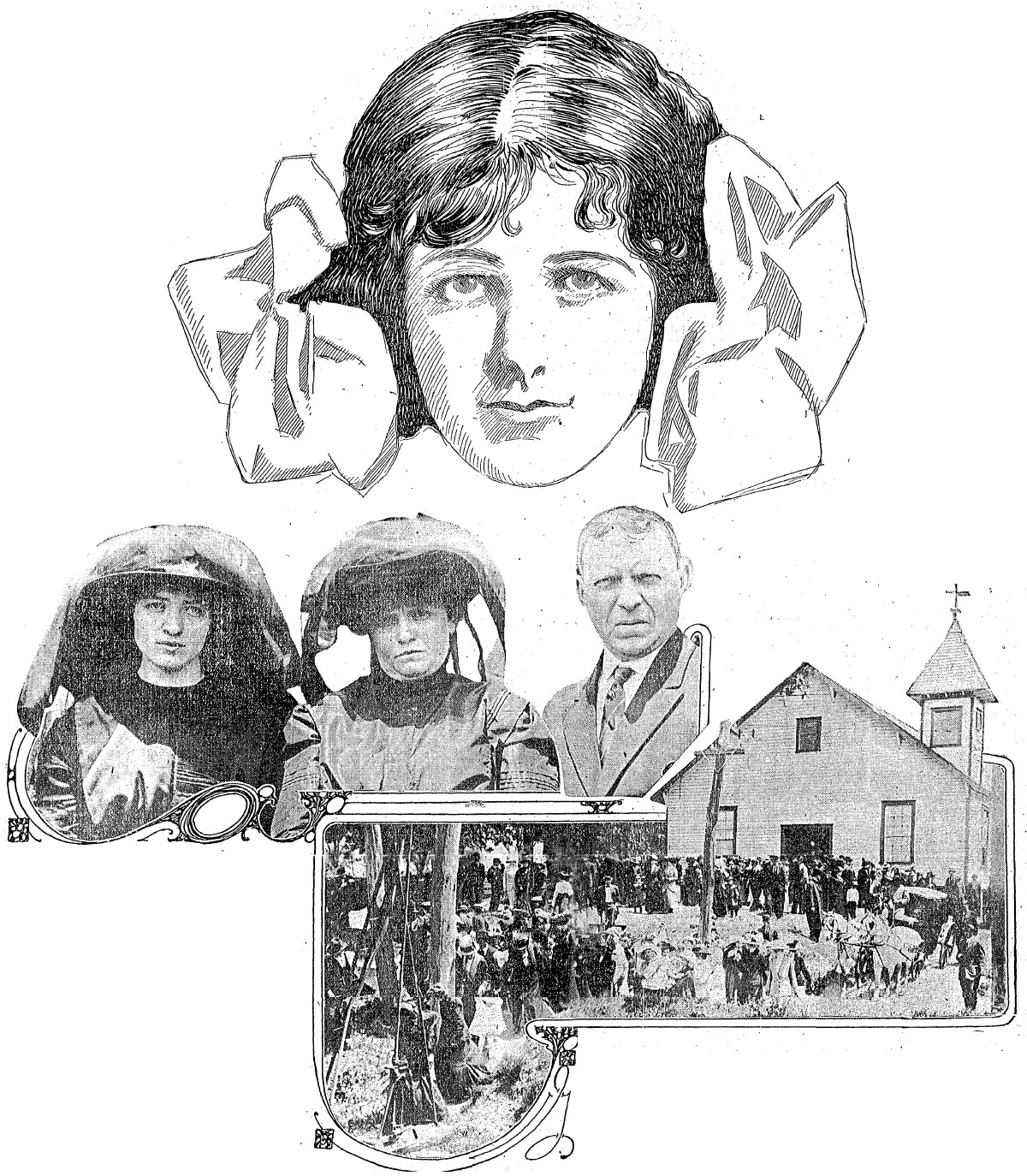

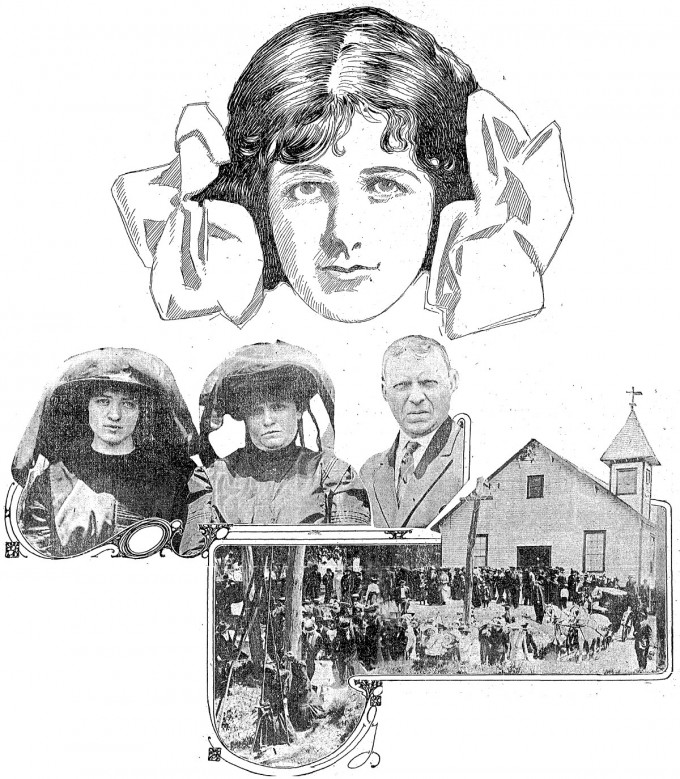

At the top is a sketch made by Henderson from the last photograph taken of little Mary Phagan, the 14-year-old girl of tragedy. Below is a photograph of her mother and step-father, Mr. and Mrs. J. W. Coleman, and her sister, Miss Ollie Phagan. The other picture was taken at the funeral.

Could you walk for hours in the heart of Atlanta without seeing a person you know?

What did Atlanta detectives do to keep murderer from “planting” evidence against suspects?

Are all the men who have been held as suspects marked men for the rest of their lives as the result of a caprice of circumstance?

This not the story of Mary Phagan. It is a story about the story of Mary Phagan.

All of the story of little Mary Phagan that can be learned has been told simply and without further sensation than the facts themselves afforded in the columns of The Atlanta Constitution from the time of this paper’s exclusive story of the grewsome discovery of the girl’s body last Sunday morning. It is, therefore, not for this story to shed light on the case, but merely to point out and discuss a few of the extraordinary phases of the most extraordinary case that has ever shocked a city.

The story of the death of Mary Phagan is the most improbable chain of events that has ever occurred within the lifetime of Atlanta. And these events have gripped and stirred the people of Atlanta as nothing that has ever happened before.

Aside from the mystery which shrouded the slyer of the girl, the thing which has held the sympathies of a whole city, as if Mary Phagan were the daughter of each person, is the youth and innocence of the little girl. She was just a little girl. When that has been said about Mary Phagan, all has been said. All testimony that has been brought out shows that she was all in simplicity, guilelessness and purity that is implied in that simple statement.

There have been other cases—recent cases—which have interested the public and appealed more or less to their sympathies, but the principals in the cases were as different as the world is wide. In the other cases there was maturity and experience, worldly wisdom and pasts that came home to roost. In all the interest and sympathy there was a subcurrent that ran chill and repellant. In past cases, could all the tears blot out one word of the sordid tales of illicit loves and intrigues? Could the “leopard skins” change their spots?

No, Lady Macbeth, No Spotted Hand.

But in the story of Mary Phagan there were no words or sentences through which she or any one would have cared to have traced a killing line. There were no stains from a spotted past to shriek their shame to the world. There was no Lady Macbeth in the past of Mary Phagan to wander through the halls of her conscience and scrub with frenzy at the tiniest speck of wrongdoing upon her white hands!

Mary Phagan’s life was one of such beauty and purity that when the world knew of her her memory instantly became the fondled child in the heart of every parent and the playmate of every little girl in the city.

There was also the impenetrable mystery of it all. The haunting of a score of horrible secrets that persecuted and compelled the mind to more than mere idle curiosity.

It seems utterly beyond the bounds of reason that a person with a thousand friends could in the twinkling of an eye drop from the face of the earth—vanish into thin air in the heart of a city of 200,000 souls!

A Life Vanishes Into Air.

Yet from the moment that a street car motorman saw little Mary Phagan walking down Hunter street toward the National Pencil factory at noon Memorial day there was nothing to indicate that of all the hosts of friends who knew her a single one ever laid eyes on her with the blood of life in her veins. There came those—scores of them—who said, “I saw Mary Phagan here at such and such a time,” and, “I saw the girl at the other place at this hour,” but never a man of them all in the final test could prove that “it was Mary Phagan whom I saw!”

Do you think that you, who are reading this, could walk on any street in the heart of the city under the light of the sun for any considerable length of time—for as much as an hour—without meeting and speaking to some friend or acquaintance?

Yet this marvel apparently happened in the heart of Atlanta! It was as if you yourself had watched Mary Phagan when she stepped off the car and walked for half a block down Hunter street, and then maybe you unconsciously blinked your eyes for minutest fraction of a second, and when you opened them again—Mary Phagan was not there! It was as if some invisible master of the black art had whispered a magic word, and—Presto! In the act of taking a step Mary Phagan was gone—as utterly vanished as the snows of yesteryear!

Notes Written By a Light.

That they were written by a light is beyond all question. Each line of the notes follows accurately the ruling of the paper upon which they were written. Could this have been accomplished in the darkness of the remote corner where her body was found? Where then could they have been written?

One note says, “He pushed down this hole.” At the bottom of “this hole” is the only light in the basement—a single sickly gas jet.

Two days after Newt Lee was arrested, a bloody shirt was found at his home. Why did the detectives wait two days after Newt Lee was arrested before they searched his home for evidence? And who was watching his home in the meantime to see that evidence was not “planted?”

Three days after the murder the register of the watchman’s time clock showed three discrepancies of an hour each. Possibly the clock was registered correctly Sunday. Who was watching to see that it was not changed?

Others were in the building on Monday besides employees. The factory was operated on Tuesday and Wednesday. Others not connected with the factory were allowed to enter the building.

As a matter of fact what detective was watching Leo M. Frank’s home to see that no one entered it and stole a monogram handkerchief, say, stained it with blood and placed it in the basement of the building, where the girl’s body was found? What did the detectives do to keep the real murderers from planting evidence against those under suspicion?

And, do you think it was possible for the letter which purported to have been dropped by Mary Phagan on the street car in which she came into the city Saturday at noon to have been undiscovered in that street car until Wednesday when it was first discovered—four days after she was last on the car?

Who Planted The Evidence?

Is there in your mind, reader, a question as to whether there was someone at large who was very, very busy while Newt Lee, Leo Frank, Arthur Mullinax and J. M. Gantt languished in jail?

Again—the mystery!

Who had been “planting” the evidence?

And why?

And what about Newt Lee, Frank, Mullinax and Gantt? Are these marked men for the remainder of their lives? Will they go through life always with a finger pointing at them and some one saying “There is the man was mixed up in that murder?” Are they victims of circumstance? Has a caprice of chance placed a brand upon them for life?

At this minute I glance out my window. Out of the darkness looms the building of the National Pencil company, and from a window in the top story shines dimly one wee little light. Except for this there is nothing but darkness, gloom, great haunting shadows and mystery.

This scene seems, somehow, to typify for me the case of Mary Phagan, and that one tiny light is little Mary herself—the only bright spot in the whole horrible story!

* * *

Atlanta Constitution, May 4th 1913, “The Case of Mary Phagan,” Leo Frank case newspaper article series (Original PDF)