Another in our series of new transcriptions of contemporary articles on the Leo Frank case.

Atlanta Journal

Friday, May 30th, 1913

Gruesome Part Played By Him Illustrated

In Presence of Detectives, Factory Officials and Newspaper Men, the Negro Goes Over Every Point of His Statement From the Time Frank is Alleged to Have Directed Him to the Metal Room Until Girl’s Body Was Left in the Basement

“MR. FRANK AND HIS FRIENDS HAVE FORSAKEN ME AND I DECIDED TO TELL THE WHOLE TRUTH,” HE DECLARES

He Says His Statement Is Voluntary, That He Has Not Been Browbeaten Nor Mistreated by the Detectives—Full Story of His Confession to Being an Accessory After the Fact and His Visit to the Pencil Factory—Frank Makes No Comment

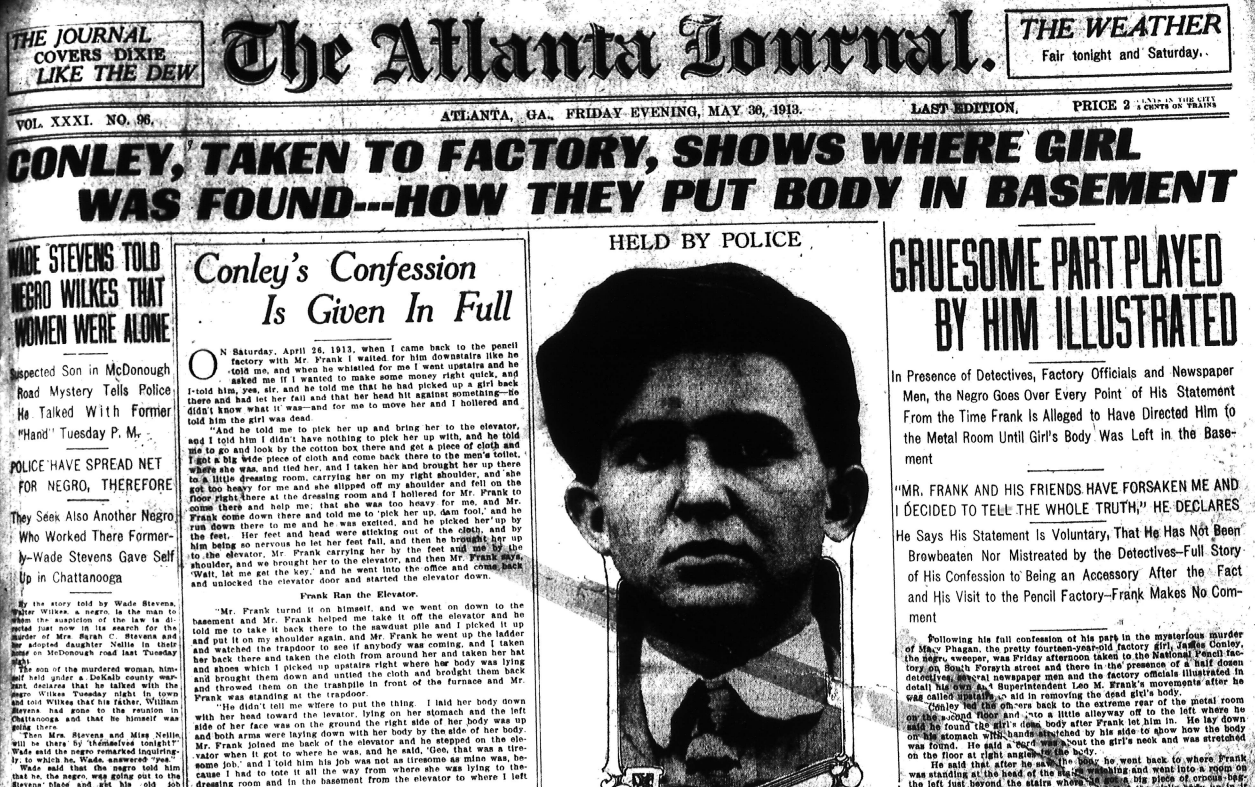

Following his full confession of his part in the mysterious murder of Mary Phagan, the pretty fourteen-year-old factory girl, James Conley, the negro sweeper, was Friday afternoon taken to the National Pencil factory on South Forsyth street and there in the presence of a half dozen detectives, several newspaper men and the factory officials illustrated in detail his own and Superintendent Leo M. Frank’s movements after he was called upstairs to aid in removing the dead girl’s body.

Conley led the officers back to the extreme rear of the metal room on the second floor and into a little alleyway off to the left where he said he found the girl’s dead body after Frank let him in. He lay down on his stomach with his hands stretched by his side to show how the body was found. He said a cord was about the girl’s neck and was stretched on the floor at right angles to the body.

He said that after he saw the body he went back to where Frank was standing at the head of the stairs watching and went into a room on the left just beyond the stairs where he got a big piece of crocus-bagging; that he took this bagging back and tied the girl’s body up in it much after the fashion a washerwoman tied up her soiled clothes; that he then took the body on his right shoulder and started up toward the elevator in the front (Frank remaining at the head of the stairs and just outside the double doors to the metal room all the while.)

Conley declared that when he had walked half way up the room the body slipped off his shoulder to the floor. (This was the place where the bloodspots were found and where it has hitherto been believed the girl was murdered.)

FRANK HELPED HIM CARRY HER.

“I then went to Mr. Frank,” said the negro, “and told him the girl was too heavy for me to carry alone. Mr. Frank then left his position and walked back with me. He took hold of the foot end of the bundle and I the head. We carried her then to the elevator and put her down on the floor while Mr. Frank went into the office to get the key to the elevator switch. On the way to the elevator Mr. Frank let the feet fall. (The negro indicated the spot where this occurred.) The elevator door was open and the bars were raised so that we did not have to stoop. We put the body on the elevator with the feet toward the front. I stood at the head and Mr. Frank, who ran the elevator down, stood with one of his feet over one of the girl’s legs which stuck out.

“When we reached the basement Mr. Frank gathered up the feet and me the head. We carried the body about twenty feet to the gas light and Mr. Frank dropped his end. He told me to pick it up and carry it back to the far end of the basement. I did so and placed it face down in the spot where it was found by Newt Lee, the night watchman.

FOUND HAT AND SHOE.

“I then removed the crocus bagging from around the body and found the hat, one shoe and a piece of ribbon had become detached. I took these along with bagging in my hand and called to Mr. Frank, who had climbed up the ladder to the cubby hole on the next landing and asked him what I must do with them. He told me to throw on the trash pile just in front of the boiler and just beside where I was standing at the time. I did as he directed. He then told me to run the elevator on up.

“When the elevator reached the landing where Mr. Frank was standing awaiting it h[e] stepped on almost before it stopped and fell heavily against me, grabbing me about the shoulders. When we reached the second floor—the office—the elevator stopped about a foot below the floor, and Mr. Frank was so excited he stu[m]bled out, falling on his knees. (The negro illustrated how Frank fell).

“After he got up he took me around the shoulders and led me straight into the inner office, closing all doors behind us. He told me to sit down at this desk (indicating a desk just back of the chair to Frank’s own desk, the chairs of each desk almost touching their backs.)

“Mr. Frank sat down in his swivel chair and turned and twisted for a moment, turning first white and then red, and sort of gasping as he talked. We heard footsteps outside and Mr. Frank hurried me itno [sic] this wardrobe (indicating the wardrobe and climbing into one side of it). Mr. Frank closed the door and remarked: ‘There comes Emma Clark and Corinthia Hall. Be right still. I will be back in a minute.’ He went outside and I heard him talking to some one, the voice sounded like that of a woman. I heard the strange voice say: ‘Are you all alone?’ and Mr. Frank said: ‘Yes.’

“A minute or two later I heard the footsteps going out of the office and Mr. Frank came back, closing the office doors behind him. He then told me to come out of the wardrobe and motioned to me to sit back down in the chair behind his.

SWAYED LIKE HE WAS SICK.

“For a minute or two he clasped his hands and swayed about in his chair as if he was sick. Then he turned to me and told me to write on a pencil pad which was lying on the desk beside me. He dictated and I wrote: ‘That long, tall black negro did this by hisself.’

“Then he pushed his hands through his hair and mumbled: ‘Why should I hang when I have got rich folks in Brooklyn, New York. Then he took a yellow pad out of his desk. (The negro indicated the exact place on the right hand of the desk where he said the yellow order pad was taken from by Frank.)

“He handed me this pad and then told me to write another note. He dictated this note also and as far as I can it was like this (and the negro wrote the following on a pad without prompting):

“Dear mother a long tall black negro did this by hisself he told me if I wood lay down he wood love me play like the night watchman did this boy hisself.’

“Mr. Frank was just twisting in his chair all the time, and just rubbing his hands together. I asked him why he wanted to put that about the night watchman in the note, and he said ‘that’s all right. I’ll fix that. I am going to send these notes to my mother, who is rich, and she’ll send you something.’ The[n] he repeated: ‘Why should I hang; my people are rich?’ and I said, ‘that’s all right, Mr. Frank, but what’s going to become of me; ain’t you going to do anything for me for helping you carry the body down?” Mr. Frank said: ‘Yes, don’t you worry.’ He then took the notes from my hand and put them on his desk, after which he placed the inkstand on top of them. (The negro illustrated by picking up the inkstand on Frank’s desk and placing it on the notes he had just written.)

“Then Mr. Frank turned around in his chair, facing me and sorter laughed. After which he got red in the face, then white, then red again. He seemed very much excited.”

CONFESSION VOLUNTARY.

At this point in his narrative Conley interrupted by Detective Chief Lanford and asked to state in the presence of all those standing around him if he had made his confession of his own free will.

“’Yes, sir,’ replied the negro, ‘I am telling this because I want to tell it. I have been upholding Mr. Frank because he told me that Saturday that he would see me Monday if he lived and make it all right with me.”

“Have you been abused or threatened by the officers into making this confession?” inquired Chief Lanford.

“No, sir,” said the negro; “the officers have treated me kindly.”

“Why did you change your first statement?” interrogated Chief Beavers.

“Because I was upholding Mr. Frank until I saw the newspapers in the chief’s office and learned that everybody at the factory was trying to put the blame on me; then I decided to tell the whole truth.”

One of the officers asked Conley if Frank had not given him some money while he was sitting in the office after he wrote the notes, and the negro replied:

TOOK MONEY BACK.

“Yes, sir; he handed me a roll of bills and said it was $200. I took it in my hand and in a little while he told me to let him see it. I thought he wanted to count the money, but he put it in his pocket and told me he would see me Monday if he lived. He had given me a cigarette box in which there was $2.50, and after he took back the roll of bills I asked him if I could have [1 word illegible] in this box and he said I could.

AFFIDAVIT MADE PUBLIC.

The third affidavit of James Conley, the negro sweeper at the National Pencil factory in which he declares that he assisted Superintendent Leo M. Frank in disposing of the murdered body of little Mary Phagan, has been made public.

The affidavit confirms The Journal’s exclusive story in Thursday’s night extra and confirms the detailed account of the confession given exclusively in The Journal’s early morning edition on Friday.

The negro’s third affidavit is the most sensational development in the Phagan murder case since the arrest of Superintendent Frank and is regarded by the detectives as the most important link in their chain of evidence against the factory official.

The negro’s admission of complicity in the crime has not changed, however, the theory of the city detectives and the other prosecuting officials, who, with Conley still charge the crime to Leo M. Frank.

In the third affidavit the negro Conley alleges in substance that Frank told him to go to the machine room and bring out the body of a girl he had hurt; that he found the girl dead, but at Frank’s direction started to carry her out; that the body slipped from his shoulder to the floor of a dressing room; that with Frank’s assistance he carried it to the elevator using a wide piece of cotton cloth as a bier; that Frank ran the elevator to the basement; that he (Conley) placed the body on his shoulder and at Frank’s direction carried her to the trash pile; that he picked up the hat and shoes from the place where she fell and threw them into the basement; that Frank took him into his private office and hid him in a wardrobe there, while he went out and talked to two ladies, who came up the steps; that when the women left he wrote the alibi notes at Frank’s dictation and that then the superintendent gave him [1 word illegible] in bills, but took them back, saying that he would give them to him on Monday; that then he was dismissed.

COMMITTED TO TOWER.

On Thursday, Judge L. S. Roan, of the criminal division of the superior court, on the petition of Solicitor General Hugh M. Dorsey, signed an order committing James Conley to the Fulton county jail to be held as a material witness in the case against Leo M. Frank. He was allowed to remain at police headquarters Thursday night as a courtesy to the detectives.

If Frank persists in his story, the solicitor general declares that he will be indicted as an accessory after the fact of the murder.

ONE TO THREE YEARS.

If found guilty on this charge Conley will escape with the comparatively light punishment of service of from one to three years in the penitentiary.

The solicitor’s statement that Conley will probably be indicted as an accessory after the fact is considered of unusual significance since it shows that despite the confession of the negro, the theory of the authorities that the man indicted by the grand jury is guilty of the crime has not changed.

An official who is fully cognizant of every statement made by Conley in his startling confession Thursday afternoon, is authority for the statement that the negro’s admissions have not yet changed the aspect of the state’s case.

An accessory after the fact is defined in the criminal code of Georgia, section 17 as “a person with full knowledge that a crime has been committed, conceals it from the magistrate, harbors, assists or protects the person charged with or convicted of the crime.”

In most cases the accessory after the fact is punished as for a misdemeanor.

For murder cases, however, section [number illegible] of the criminal code of 1911 says: “If any person shall receive, harbor or conceal any person guilty of a crime punishable by death or imprisonment, and labor in the penitentiary knowing such person to be guilty, such person so receiving, harboring or concealing shall be deemed an accessory after the fact, and shall be punished by imprisonment and labor in the penitentiary for not less than one year nor longer than three years.”

Should the state be able to show that Conley knew that a crime was being committed in the building, although he was not present and did not see the actual commission of the crime, still, under the law, the negro would be a principal in the second degree, and his offense would be punishable with death.

Apparently, however, it is not the intention of the authorities to press any charge against the negro except that of accessory after the fact, and thereby they give full credence to his story.

FRANK IS SILENT.

Superintendent Leo M. Frank, Friday, declined to comment in any wise upon the Conley confession made to the police. The accused man refused the request of a Journal reporter that he or his advisors make a statement relative to Conley’s admissions.

During the day Frank received a number of friends in his cell at the Tower and read every issue of the newspapers, apparently with keen interest. While none of his advisors would talk, it seemed to be agreed tacitly that no statement would emanate from Frank or his friends until Luther Z. Rosser, his attorney, returned from Clayton and [1 word illegible] be apprised of the new turn the Phagan mystery had taken during his absence.

Confession Followed Gruelling Examination

Conley’s latest confession has created a tremendous sensation about police headquarters.

He made the confession during the course of a sweating which lasted from 2 o’clock Thursday afternoon until nearly 6 o’clock.

The officers present while the negro was being examined were Chief Beavers, Chief of Detectives Lanford, Detective Pat Campbell and Harry Scott, of the Pinkertons.

SOLICITOR KEPT INFORMED.

As the sensational statements were being dragged sentence by sentence from the frightened negro, the officials who were in Chief Lanford’s office were in constant communication with Solicitor General Hugh M. Dorsey. Several times Newton Garner, trusted attaché of the solicitor’s office, was called in conference by Chief Lanford and each time he carried his report to the solicitor.

When the examination was over and Conley, the sweat pouring from his brow, had been led back to his cell, reporters were admitted to the chief’s office, but the only official statement given out was that the negro had made a third affidavit. Chief Lanford stated that there were reasons which made him desire not to give out the details of the negro’s confession.

In ten minutes after the conference was over, however, The Journal night extra, carrying the exclusive story of the negro’s new confession, reached headquarters, and none of the officials would say that any portion of the story was incorrect.

CONLEY’S SEVERAL STATEMENTS.

The piece-meal confessions of the negro Conley are playing an important part in the Phagan case.

Conley knowing that he had been trapped in lies, made his first admission on last Saturday at the time when the jury was preparing to indict Leo M. Frank for the crime. He then told officers that he wrote the notes found by Mary Phagan’s body on Friday before the crime.

The officers got specimens of his handwriting, which they say show conclusively that he wrote the notes found by the murdered girl’s body.

They could not conceive of such a crime being premeditated, however, and continued to sweat the negro. Wednesday he broke down again, and told the detectives that he wrote the notes at Mr. Frank’s dictation on Saturday, the day of the tragedy.

He told that he was secreted behind boxes on the first floor most of the morning. He told of actions of people and occurrences about the factory, which he could not have known had he not been there on the day of the crime. The negro’s statements, except for a few discrepancies in time, which the officers attribute to the ordinary fallibility of his mind, were fully corroborated.

This convinced the detectives that Conley knew more of the crime than he had ever told and they kept hammering at him with the result that he broke down again Thursday afternoon.

While the detectives believe that Conley is now telling the truth, they think that he may know even more about the crime, especially the small details, than he told on Thursday afternoon, and they say that they are not going to rest until they are satisfied that he has told the whole truth.

WENT TO CONFRONT FRANK.

The detectives are still extremely anxious that Conley be allowed to face Frank and tell his story to him.

They believe that the negro cannot tell the full story before the factory official without the nerve of one of the two men breaking down and throwing a new light on the tragedy.

Luther Z. Rosser, counsel for Mr. Frank, is expected to return to the city during the day Friday and efforts will then be made to get his permission to confront Frank with the negro.

Sheriff Mangum has consistently refused to allow the negro to go to Frank’s cell with the detectives unless Frank gives his permission. No superior court judge is expected to give an order allowing the interview if Frank objects to it, and as a result the matter depends on the attitude of Attorney Rosser.

* * *

Atlanta Journal, May 30th 1913, “Conley, Taken to Factory, Shows Where Girl Was Found—How They Put Body in Basement,” Leo Frank case newspaper article series (Original PDF)