A NEW authorized audio book version of The Murder of Little Mary Phagan by Mary Phagan Kean has just been recorded for The American Mercury. The Leo Frank Case Research Library is proud to offer it to our readers on this, the 103rd anniversary of the tragic death of Mary Phagan.

You can download the audio book, free of charge, below.

The Murder of Little Mary Phagan is an exceptionally insightful semi-autobiographical book, detailing a fascinating exploration of one of the most sensational criminal cases of all time. What makes this book so intriguing is it provides an intimate view of the Frank-Phagan case from the adult grandniece of the teenage victim — little Mary Anne Phagan, the tragic child laborer who was murdered on April 26, 1913, in Atlanta, Georgia.

This true crime monograph is widely regarded as the most even-handed book ever written about the Frank-Phagan affair (1913-1915) and its contentious aftermath (1915-1986). It also provides facts and evidence about the case found in no other book. Mary Phagan Kean also offers a uniquely neutral analysis of the month-long capital murder trial which ended in Frank’s conviction.

Mary Phagan Kean is the namesake of the murder victim, Mary Phagan, being her grandniece. When the author was 13 years old, she discovered her given name was no mere accident or coincidence. When people heard her name, they started asking her questions about whether she was related to the famous little Mary Phagan who had been murdered long ago by Leo Frank on Confederate Memorial Day in 1913.

When her family revealed the truth about her blood relation, she immediately became deeply interested in learning about the murder, its investigation, and its aftermath. She has since devoted thousands of hours of her life studying volumes of legal documents, conducting interviews, and reading every surviving newspaper account of the case. This written-from-the-heart book is the result. (The Murder of Little Mary Phagan; Far Hills, NJ, New Horizon Press, 1987, 316 pp.)

Download the complete audio book as one zip file

You can also download the individual chapters.

You can also play the individual chapters by pressing the play buttons below:

Introduction and Chapter 1; “Are You, By Any Chance . . . ?”; 18 minutes:

Chapter 2; The Legacy; 1 hour 10 minutes:

Chapter 3; My Search Begins; 42 minutes:

Chapter 4; The Case for the Prosecution; 1 hour 20 minutes:

Chapter 5; The Case for the Defense; 1 hour 30 minutes:

Chapter 6; Sentencing and Aftermath; 37 minutes:

Chapter 7; The Commutation; 1 hour 30 minutes:

Chapter 8; The Lynching; 43 minutes:

Chapter 9; Reverberations; 13 minutes:

Chapter 10; Alonzo Mann’s Testimony; 37 minutes:

Chapter 11; The Phagans Break Their Vow of Silence; 21 minutes:

Chapter 12; Application for Pardon, 1983; 1 hour 21 minutes:

Afterword; Pardon, 1986; 11 minutes:

Appendix 1

A Review of The Murder of Little Mary Phagan

The Murder of Little Mary Phagan was written by Mary Phagan Kean (born Friday, June 5, 1953) and published by New Horizon Press on September 15, 1989.

This book is the most even-handed available on the Leo Frank-Mary Phagan murder case, which is all the more extraordinary since it comes from the pen of a woman who is the namesake and blood relative of the victim.

Ms. Kean’s grandfather was Mary Phagan’s older brother, and he recognized an uncanny resemblance between his great-niece Mary and his long-dead sister. The book recounts an incident that took place in 1968:

I decided to ask my grandfather, William Joshua Phagan, Jr. about his little sister. Of all people in our family, he’d be the one to know about the pretty girl for whom I’d been named.

But my grandfather was beginning to show his age then. His light blue eyes reflected the continual tiredness he felt. His balding head glittered in the sunlight. He’d had a stroke earlier and his communication skills were hampered, so I decided to wait until the right moment to ask him my questions.

One day, to everyone’s surprise, my grandfather came out with little Mary’s picture and pointed to me. As he looked at the picture and then me, he sobbed, and as he tried to find the words, nothing came out but low sobs and wailings.

The Apocryphal Deconstructed

Mary Phagan Kean — though scrupulously fair to Leo Frank and his innumerable partisans — successfully dispels one of the central conspiracy theories perpetuated by Frank’s defenders — the disingenuous thesis that Leo Frank was suspected, indicted, convicted, denied his appeals, and hanged because of widespread Southern anti-Semitism. (Frank was Jewish.)

First, let’s take a brief look at the main facts of the case, which are well-reported in the book.

In the Yawning Darkness:

Early Sunday, April 27, 1913

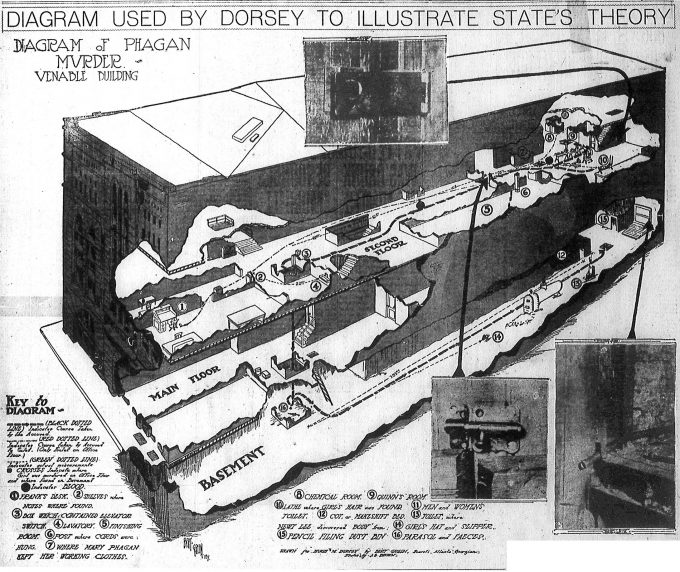

After old Newt Lee, the newly hired African-American night watchman at the National Pencil Company, punched the time clock in Leo Frank’s second floor business office at 3:01 AM., he went down to the stygian basement to use the toilet reserved for Black employees there –remember, this was 1913 in the segregated South. When he went immediately afterwards to check the large steel-framed door of the cellar service ramp, something out of the ordinary appeared faintly in the gloom.

As Lee held his flickering smoky lantern closer, he saw a dead child who had been horribly mauled. Lee stepped back in a state of shock and disbelief, briskly retraced his steps, climbed up the ladder to the ground floor lobby, and then ran up the flight of stairs to the second floor to telephone his superintendent, Leo Frank. After eight minutes of trying to reach him, no one had answered. So he called the Atlanta police station.

Newt Lee’s grisly discovery was the impetus for a police investigation that began precisely at 3:24 AM on Sunday, April 27, 1913, when the graveyard shift call-officer, W.F. Anderson, received Lee’s frantic call. A squad car filled with officers and Britt Craig (a young, one-year veteran of the Atlanta Constitution‘s news team) was immediately dispatched by Anderson moments later. What happened next was later revealed at the Leo Frank trial more than three months later, as first responders described in detail on the witness stand what had happened from their arrival at 3:40 AM until 7:00 AM — when they finally reached Leo Frank by telephone.

As dawn broke, after Frank repeatedly failed to answer the phone, the police finally made contact with him when he answered at about 7:00 AM. They informed him they were coming to his residence to speak with him, though they did not tell him what specifically had been discovered at the factory. Police rushed over to the Selig residence, then took him directly to the morgue to identify the dead body. After Frank claimed to be unsure about the identity of the dead girl, police officers drove him to the factory in an effort to have him pinpoint the approximate time of Phagan’s arrival via his accounting books.

The Timeline is Born:

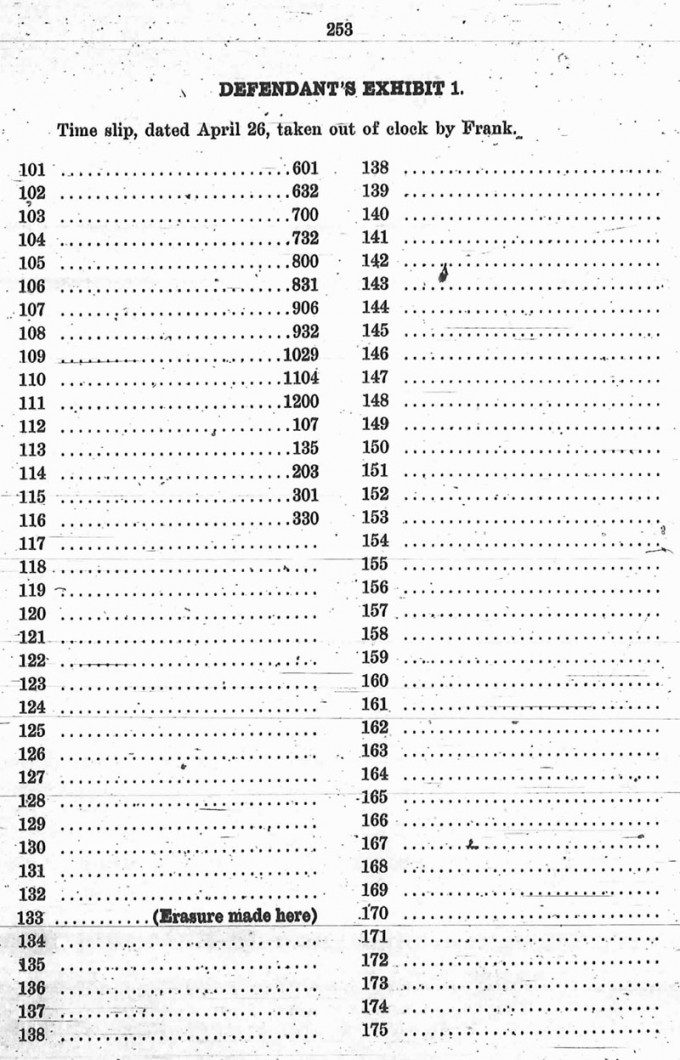

“Saturday, April 26, 1913 at 12:03 PM”

Inside his business office, at about 8:00 AM, Frank opened his payroll ledger and told the police officers that Mary Phagan had arrived at about 12:03 PM on Saturday, April 26, 1913, asking for her pay envelope and, upon receiving it, had left. Frank went on to tell the police he stayed continuously in his business office from that time until 12:45 PM on that fateful day.

The next day, Monday morning, April 28, 1913, Leo Frank would change the time of Phagan’s arrival to his office from 12:03 PM to “12:05 PM to 12:10 PM, maybe 12:07 PM.” (State’s Exhibit B, Leo Frank Trial Brief of Evidence, 1913; Atlanta Constitution, August 2, 1913).

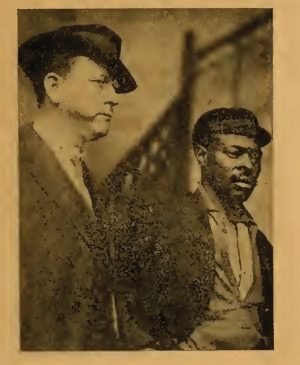

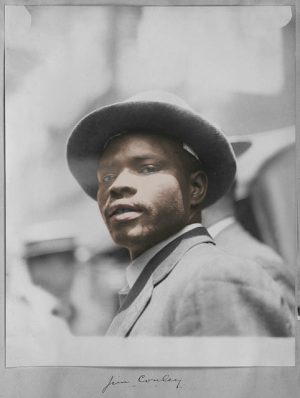

Leo Frank was arrested on suspicion of murder on Tuesday, April 29th, at 11:35 AM. It would be his last day of freedom. On Thursday, May 1, two days after Frank’s arrest, Jim Conley, the factory roustabout, was also arrested.

Milestone in the Mary Phagan Murder Investigation

Something very interesting happened exactly one week after the murder of Mary Phagan — on Saturday, May 3, 1913. The event was an unexpected surprise. The major breakthrough occurred when detectives stumbled upon one of the young female child laborers who was tendering her resignation at the National Pencil Company (NPC). This significant former employee was 14-year-old Monteen Stover — who was accompanied by her incensed stepmother — making what astonishingly turned out to be a second attempt at collecting her pay envelope, because she had failed to retrieve it the first time on the day of the murder, when she came to the factory alone at five minutes past noon.

When police detectives thoroughly questioned Monteen Stover, she revealed something rather curious that would become the crux of the entire murder case: Little Miss Stover said that when she had arrived at the pencil factory exactly one week before and made her first attempt to get her weekly wages, she was unable to do so because Leo Frank was not inside his office. This was unusual, as he normally was in his office at the normal payoff time — which was regularly designated as Saturdays at noon. Stover said that Leo Frank’s office was empty on that tragic day the entire time she waited inside it — from 12:05 PM to 12:10 PM. She stated that she knew the exact times based upon her observation of the office’s wall clock.

When police detectives thoroughly questioned Monteen Stover, she revealed something rather curious that would become the crux of the entire murder case: Little Miss Stover said that when she had arrived at the pencil factory exactly one week before and made her first attempt to get her weekly wages, she was unable to do so because Leo Frank was not inside his office. This was unusual, as he normally was in his office at the normal payoff time — which was regularly designated as Saturdays at noon. Stover said that Leo Frank’s office was empty on that tragic day the entire time she waited inside it — from 12:05 PM to 12:10 PM. She stated that she knew the exact times based upon her observation of the office’s wall clock.

This was earth shattering news to investigators — because on Monday, April 28, Leo Frank, in the presence of his elite attorneys (Luther Zeigler Rosser and Herbert Haas), had made an unsworn stenographed deposition to a room full of Atlanta police detectives. In this deposition Frank precisely stated he was in his office alone with Mary Phagan between 12:05 PM and 12:10 PM (State’s Exhibit B). Even more significant is that Leo Frank initially told the police on Sunday, April 27, 1913, not only that Mary Phagan had come to his office at 12:03 PM, but that he had not left his office at all until 12:45 PM.

Sunday, May 4, 1913: the Moment of Truth

Without Leo Frank knowing the police had discovered and questioned Monteen Stover, detectives John R. Black and Pinkerton detective Harry A. Scott approached Leo Frank in his jail cell on Sunday, May 4, and asked him to confirm, again, if he had been in his office every minute on Saturday, April 26, from noon to 12:45 PM. Leo Frank responded with an affirmative “Yes.” The officers then reworded and slightly changed the question and asked Leo Frank if he had been in his office every minute on Saturday, April 26, from noon to half past noon — and Leo Frank responded again with an affirmative “Yes.”

It was then eight days after the murder of Mary Phagan. The police had discovered a very odd possible discrepancy in Leo Frank’s murder alibi. Leo Frank would maintain stoically — until near the end of his trial — that he had never left his office, from noon until he went upstairs to the fourth floor at 12:45 to tell two employees he was getting ready to leave the building for dinner (what most of us would call lunch today).

Curious Inconsistency

As far as the police were concerned, the murder alibi of Leo Frank had been unintentionally shaken, and possibly shattered, by Monteen Stover. But they would have to wait three and a half months to find out how Leo Frank would account for this discrepancy — because that’s how long Leo Frank would maintain that he never left his office until 12:45. But then, something electrifying happened — something the pro-Frank forces would suppress for more than a century.

Apogee of the Leo Frank Murder Trial, August 18, 1913

At his murder trial, Leo Frank finally responded to Monteen Stover’s trial testimony. Frank finally answered specifically why his office might have been empty at the exact same time he formerly claimed Phagan was with him alone there. Frank totally changed his original alibi — that he had maintained for more than three months — about having never left his office during the critical time. In an unsworn statement on the stand, he stated that he might have “unconsciously” used the toilet in the factory’s metal room bathroom when Monteen Stover was in his office looking for him. And it was in the metal room — at that precise time — that the murder took place, according to the police.

The toilet to which Frank referred was in the metal room at the rear of the second floor, the same floor as his office, the only toilet available to him on that floor — and the metal room was the place where the murder took place. Additionally, the murder occurred at the same time Frank was absent from his office.

Another major breakthrough the investigation was the testimony of Jim Conley, the NPC sweeper who ultimately confessed to being Leo Frank’s accomplice in moving Mary Phagan’s dead body from the metal room to the basement.

Unique Trial Analysis

Mary Phagan Kean also offers a uniquely neutral analysis of the month-long capital murder trial, which began on July 28, and led to Leo Frank’s August 25, 1913 murder conviction, after the jury deliberated for about two hours. The jury’s decision also included a “without mercy” recommendation to the presiding judge — suggesting that a death sentence be meted out to Leo Max Frank.

Both the conviction and sentencing recommendation were affirmed the next day by the presiding judge, the Honorable Leonard Strickland Roan. Judge Roan sentenced the defendant Leo Frank to death by way of hanging as prescribed by law. The execution date was first scheduled for October 10, 1913 — but appeals postponed the execution date repeatedly for two more years.

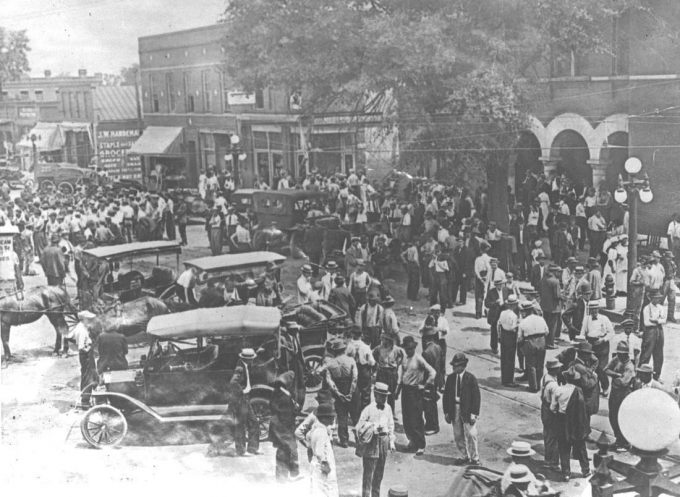

Leo Frank’s subsequent failed appeals, initiated from August 1913 to April 1915, and the eventual commutation of his death sentence to life imprisonment by a corrupt outgoing governor, John M. Slaton, on June 21, 1915, led to a mob of 1,200 angry citizens protesting at the governor’s mansion. The angry crowd was quelled and dispersed by the state militia.

The Law Firm of Luther Rosser, Morris Brandon,

John Slaton, and Benjamin Phillips

Rarely ever mentioned in connection with Leo Frank’s commutation is the fact that Governor John M. Slaton was part owner of the law firm representing Leo Frank at his trial and appeals. The law firm was officially called Rosser, Brandon, Slaton, and Phillips — and this politically powerful law group had been formed before Leo Frank’s trial began.

Governor Slaton had essentially commuted the death sentence of his own client — after that client had suffered two years of failed appeals at every possible level of the United States legal system. Naturally, the public became outraged at the obvious conflict of interest and Slaton’s betrayal of his sworn oath, of his legal ethics, of his public trust, and of his office.

Here’s how Mary Phagan Kean recounts her first awareness of those facts, in a conversation she had with her father (Mary Phagan’s nephew) when she was 15 years old:

“Daddy, why did Governor Slaton commute Leo Frank’s sentence?”

“This is one question that our family still asks today. We do not accept Governor Slaton’s explanation in his order. There had to be something else. No man will willingly commit political suicide; but he did just that with the commutation order. I’ve done some research on my own, but I know no more today than my grandmother did back in 1915. I’ve found certain things about Governor Slaton that are hard to accept but are facts.

“The Atlanta newspapers of 1913 show the law firm of Rosser & Brandon, 708 Empire, and the law firm of Slaton & Phillips, 723 Grant Building, as merging. Then the 1914 Atlanta Directory shows the law firm of Rosser, Brandon, Slaton & Phillips, 719—723 Grant Building. They were also listed in the Atlanta Directory in 1915 and 1916. Slaton was a member of the law firm that defended Leo Frank.

“Governor Slaton was a man that Georgia loved and admired until June 21st, 1915. Then love turned to hate. The people believed that Governor Slaton had been bought. His action caused the people of Georgia to take the law into their own hands, to form a vigilante group and seek justice that they believed had been denied them.”

The Ugly Racist Framing of

the Night Watchman Newt Lee

On Sunday morning at 8:26 a.m., April 27, 1913, in the presence of the Atlanta police, Leo Frank pulled out Newt Lee’s time card, eyeballed it from the top downward, and said it was punched correctly every half hour — meaning that Lee had made all his rounds on time and would not have had enough time to leave the building and go to his home between punches. However, the next day Leo Frank changed his story and told the police that Newt Lee did not punch his time card correctly and that there were missing punches indicating four hours of unaccounted-for time. This put even greater suspicion on Newt Lee. The intervals suggested he had more than enough time to go home, potentially hide evidence, and then return to the factory.

Intimations to Search Newt Lee’s Shack

After Frank made his Monday morning, April 28, 1913 deposition to the Atlanta Police that became known as State’s Exhibit B, he told the police to check his body for scratches and visit his home to inspect his laundry for blood stains. Leo Frank removed his shirt and the police found no visible scratch marks on his body. At Frank’s residence, the maid brought forth the dirty laundry basket and the clothes within it — and no blood stains were found on any of them. Given Leo Frank’s intimations about Newt Lee’s time card, the natural thing for the Atlanta Police to do next was search Newt Lee’s home for evidence. And, surprise surprise — you can probably guess what they found.

On Tuesday morning, April 29, 1913, the police entered Newt Lee’s shack without a warrant, using a skeleton key. Just outside his residence, at the bottom of a garbage barrel, they found a suspicious-looking otherwise clean but heavily bloodied shirt. The shirt had blood stains right up to the arm pits in the front, back, and inside — overdone to the point that the police suspected it was forged and planted there intentionally. What also made detectives think the shirt might have been planted is the fact that, aside from the oddly-placed blood stains, it appeared clean and did not have any body odor indicating it had even been worn since the last time it was washed.

These are just a few of the facts discovered by investigators in this murder case. I urge you to read The Murder of Mary Phagan and the other sources mentioned and linked below for a fuller understanding. But surely what I have adduced thus far is enough to show you why investigators — and, eventually, jurors — believed that Leo Frank was the most likely suspect.

The planted shirt — the time card that somehow lost four hours’ worth of punches overnight — and the absolutely contradictory testimony of Frank and Monteen Stover — all these circumstances made investigators begin to suspect Leo Frank. It had absolutely nothing to do with “anti-Semitism.”

All this is made clear in Phagan Kean’s book, although the author bends over backwards, chapter after chapter, to be more than fair to Frank. After reading this book, it will simply be impossible for you to take seriously the lurid, exaggerated claims made by biased groups like the ADL (one such claim is shown in the ADL Web site screen shot below).

Kean is not alone in her doubts about the now-popular media narrative of an innocent Frank persecuted by bigots.

Even Frank’s wife, Lucille, may have had doubts about his innocence in the end. After she died in 1957, it was discovered that she did not, as everyone expected her to do, want to be buried in Brooklyn’s Mount Carmel Cemetery next to her husband Leo. Instead, she wanted to be cremated and have her ashes scattered in an Atlanta public park. The facts are related in an article by pro-Frank author Steve Oney in the March 2004 issue of Georgia Magazine:

On the same day I met Gene Clay in Sarasota, I spent several hours up the road in St. Petersburg with Alan and Fanny Marcus, two Atlantans who’d retired to Florida.

Alan was Lucille Frank’s nephew. He’d grown up at her knee and borne witness to the devastation that the lynching had wrought in her life and in the life of Atlanta’s Jewish community.

Following Lucille’s death in 1957, her body was cremated. She wanted her ashes scattered in a public park, but an Atlanta ordinance forbade it.

For the next six years, the ashes sat in a box at Patterson’s Funeral Home. One day, Alan received what for him was an upsetting call. The ashes needed to be disposed of. Alan didn’t know what to do. In the years since Lucille passed away, the Temple, the city’s reform synagogue, had been bombed. This event had set Atlanta’s Jews on edge. It was no wonder that Alan didn’t want to attract scrutiny by conducting a public burial. For months, he carried Lucille’s remains around Atlanta in the trunk of his red Corvair. Early one morning in 1964, he and his brother drove downtown to Oakland Cemetery. There, under the cover of the gray dawn light, the two men buried this martyred figure in an unmarked plot between the headstones of her parents.

Oney, whose book And the Dead Shall Rise is one of the best pro-Frank tomes, is honest enough to state that Frank’s lynchers were motivated by a desire to carry out the court’s sentence — and not by anti-Semitism. In an article in the June 11, 2000 issue of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Oney made that very clear:

“The lynching is one of the great unsolved crimes of the 20th century,” says Steve Oney, a Los Angeles writer who has been working on a book about the case for more than a decade. Many of the details are known from contemporary and historical accounts.

In the summer of 1915, after Gov. John M. Slaton commuted Frank’s death penalty to life in prison, a group of Cobb civic leaders calling themselves the Knights of Mary Phagan met secretly to plot the lynching. What drove them to action, Oney says, wasn’t blind anti-Semitism. It was their belief that Slaton had pulled a fast one; one of the partners in his Atlanta law firm was Luther Z. Rosser, Frank’s lead defense counsel.

Oney draws an analogy: “Imagine how people would have felt if O.J. Simpson had been found guilty and the governor of California commuted his sentence and, oh, by the way, he practiced law with Johnnie Cochran.”

How the Most Definitive Book

on the Leo Frank Case was Born

The Murder of Little Mary Phagan is written by the namesake of the murder victim, Mary Phagan’s great-niece Mary Phagan Kean. After becoming a lifelong student of the case at age thirteen, inspired by her own family’s accounts of the tragedy, Phagan Kean has since devoted almost every free moment of her life studying volumes of legal documents and reading every surviving newspaper account surrounding the rape and strangulation of her great aunt.

Most illuminating is Phagan Kean’s description of the intrigues surrounding the granting of the 1986 posthumous pardon to Leo Frank, which I’ll excerpt here:

[In March 1986 m]y father and I met with Wayne Snow, Jr., the new chairman of the Board [of Pardons and Paroles], and Mike Wing. We were told that the Jewish community had again filed application for a posthumous pardon. And that if a pardon were issued, it would be based not on guilt or innocence but on the contention that “the State did not protect Leo Frank and that his rights were violated.” The Board felt that the lynching of Leo Frank was wrong. And that this pardon would “heal old wounds.”

Apparently, renewed efforts for pardon had begun in September 1985. And while at first the petitioners had thought they’d failed to obtain the pardon in 1983 simply because they had not brought enough pressure to bear, they had come to see that, beyond the strictly procedural action of the process which sought to establish Leo Frank’s innocence or Jim Conley’s — or someone else’s — guilt, what was most probably achievable was a pardon that addressed the extra-legal case about Leo Frank.

And this approach by the petitioners allowed Board members’ sympathies for the extra-legal aspects of the case to come through. The Board had been deeply concerned about the problem of setting a precedent for a huge number of posthumous pardon applications, were Frank pardoned on strictly legal bases. By addressing the extra-legal case, however, the precedent that a pardon would grant would only be to exceptional cases like the Frank case. So, six months prior to the Board’s contacting me, an initial proposed pardon application made its way through to some members of the Board. This initial draft repudiated the old standard of absolute innocence and made no mention of a pardon based on innocence or guilt. By March, members of the Board had agreed in principle to grant a special type of pardon which would imply neither innocence or guilt, but merely address the concerns brought about by the case. They approved such a pardon in early March.

After meeting with representatives of the petitioners, the Board began drafting a final pardon order which they approved shortly after ADL officials and others found it acceptable.

But our family had questions.

Why was there no public announcement of receipt of application?

Why were other people who opposed granting of the pardon not told of the new application?

Former Chairman Silas Moore announced the issuance of a pardon order on March 11, 1986 at 1:00 P.M. at the Georgia State Capitol.

It seems that Board members had finally agreed on the bases for granting a pardon. They reflected concern that Frank’s lynching had foreclosed efforts to prove him innocent. The Board also addressed three extra-legal concerns — the repudiation of lynch law, the need to heal old wounds, and the acknowledgement of anti-Semitism.

The question of whether Leo Frank had really committed the murder — the search for his purity or demonhood — was now just dust in the wind. In the discussions of pardon from September through March 1986 the Board had done no detective work, except to ensure the accuracy of its final order, discussing the historic background to the Frank trial. The Board simply overlooked guilt or innocence, something it had never done in pardons of forgiveness or pardons of innocence.

The reports had indicated that the Board worked in secret with the Jewish community for almost a year and Wayne Snow, Chairman of the Board, stated this publicly during a TV station interview. This disturbed us. Wayne Snow had told us at the beginning of March that the Board was thinking of granting a pardon, but, in fact, had already made the decision which they announced immediately after they spoke to us.

We wondered what the purpose was of keeping it secret?

The purpose, of course, was to prevent the Phagan family from having any input at all with the decision.

One of the most unique and moving sections of the book is Phagan Kean’s description of the meeting between her grandfather, William Joshua Phagan, Jr. (Mary Phagan’s brother), and Jim Conley. The current theory of most of Leo Frank’s defenders is that Jim Conley was the actual killer.

Twenty-one years after the murder, in 1934, William confronted Jim Conley in private — and was ultimately convinced that the former factory sweeper was telling the truth on the stand when he said that Leo Frank was guilty of the crime and that he, Conley, had been cajoled by Frank into helping move the body.

At times so emotionally moved that he could barely hold back his tears, William Phagan finally told Conley that he believed him — and said that, if he had thought that Conley was lying, “I’d kill you myself.” After the intense meeting was over, Jim Conley and Mary Phagan’s brother went out for a drink together.

This book is full of highly-personal gems like this. I highly recommend it.

Enjoy the audio book version embedded near the top of this page, read The Murder of Little Mary Phagan by Mary Phagan Kean at archive.org, or buy the book at Amazon.com.

APPENDIX 2:

Recommended reading

Excellent sources of research and information about the Leo Frank Case include:

1. The Leo Frank Case: Inside Story of Georgia’s Greatest Murder Mystery 1913 — The first neutral book written about the murder of Mary Phagan and trial of Leo Frank.

2. American State Trials, volume X (1918) by John Lawson tends to be biased in favor of Leo Frank and his legal defense team. This case commentary review provides an abridged version of the Brief of Evidence, leaving out some of the important testimony and evidence when it republishes parts of the trial testimony. Be sure to read the abridged closing arguments of Luther Zeigler Rosser, Reuben Rose Arnold, Frank Arthur Hooper and Hugh Manson Dorsey. For a more complete version of the Leo M. Frank trial testimony, read the 1913 Leo Frank Case Brief of Evidence.

3. Argument of Hugh M. Dorsey in the Trial of Leo Frank. Some, but not all, of the nine hours of arguments given to the Jury at the end of the Leo Frank trial on August 22, 23, and 25 of 1913. Only 18 libraries in the United States have copies of these statements in book format. This is an excellent book and required reading for students of the Leo Frank case to see how Hugh Dorsey, in sales vernacular, closed the panel of thirteen men (the trial jury of twelve men plus Judge Leonard Strickland Roan).

4. Leo M. Frank, Plaintiff in Error, vs. State of Georgia, Defendant in Error. In Error from Fulton Superior Court at the July Term 1913, Brief of Evidence. Only three original copies from 1913 and 1914 exist at the Georgia State Archive.

Three major Atlanta dailies: The Atlanta Constitution, The Atlanta Journal and The Atlanta Georgian (Hearst’s Tabloid Yellow Journalism). The most relevant issues center around April 28th to August 27th 1913:

5. Atlanta Constitution newspaper: The Murder of Mary Phagan, Coroner’s Inquest, Grand Jury, Investigation, Trial, Appeals, Prison Shanking and Lynching reported about the Leo Frank Case in the Atlanta Constitution daily newspaper from 1913 to 1915. http://archive.org/details/LeoFrankCaseInTheAtlantaConstitutionNewspaper1913To1915

6. Atlanta Georgian newspaper covering the Leo Frank Case from late April though August, 1913. http://archive.org/details/AtlantaGeorgianNewspaperAprilToAugust1913

7. Atlanta Journal newspaper, April, 28, 1913, through the end of August, 1913, pertaining to articles about the Leo Frank Case. http://archive.org/details/AtlantaJournalApril281913toAugust311913

8. Leo Frank confirms he might have been in the bathroom at the time Monteen Stover said his office was empty (12:05 p.m. to 12:10 p.m.): See the Atlanta Constitution, Monday, March 9, 1914, Leo Frank Jailhouse Interview

U.S. Senator Tom Watson

8. Tom Watson’s Jeffersonian Newspaper (1914, 1915, 1916 and 1917) and Watson’s Magazine (1915). Tom Watson’s best work on the Leo M. Frank case was published in August and September 1915. Watson’s five major magazine works written serially on the Frank-Phagan affair, provide logical arguments confirming the guilt of Leo M. Frank with the superb reasoning of a seasoned criminal attorney. These five 1915 articles published over numerous months are absolutely required reading for anyone interested in the Leo M. Frank Case. Originals of these magazines are extremely difficult to find.

8.1. The Leo Frank Case By Tom Watson (January 1915) Watson’s Magazine Volume 20 No. 3. See page 139 for the Leo Frank Case. Jeffersonian Publishing Company, Thomson, Ga., Digital Source Archive.org

8.2. The Full Review of the Leo Frank Case By Tom Watson (March 1915) Volume 20. No. 5. See page 235 for ‘A Full Review of the Leo Frank Case’. Jeffersonian Publishing Company, Thomson, Ga., Digital Source www.Archive.org

8.3. The Celebrated Case of The State of Georgia vs. Leo Frank By Tom Watson (August 1915) Volumne 21, No 4. See page 182 for ‘The Celebrated Case of the State of Georgia vs. Leo Frank”. Jeffersonian Publishing Company, Thomson, Ga., Digital Source www.Archive.org

8.4. The Official Record in the Case of Leo Frank, Jew Pervert By Tom Watson (September 1915) Volume 21. No. 5. See page 251 for ‘The Official Record in the Case of Leo Frank, Jew Pervert’. Jeffersonian Publishing Company, Thomson, Ga., Digital Source www.Archive.org

8.5. The Rich Jews Indict a State! The Whole South Traduced in the Matter of Leo Frank By Tom Watson (October 1915) Volume 21. No. 6. See page 301. Jeffersonian Publishing Company, Thomson, Ga., Digital Source: www.Archive.org

Tom Watson’s Jeffersonian Weekly Newspaper

9. The archive of Tom E. Watson Digital Papers, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, contains the full collection of Jeffersonian Newspapers: http://www.lib.unc.edu/dc/watson

Modern Leo Frank cult members (known as Frankites) are posing as neutral reviewers and attempting to convince people not to read Tom Watson’s analysis about the Frank-Phagan affair. Watson’s analysis of the case is the controversial forbidden fruit of truth that have been censored for more than 100 years. For a nearly complete selection of: Tom Watson’s Jeffersonian newspaper articles specifically related to the Murder of Mary Phagan and Leo Frank Case.

Tom Watson Brown, Grandson of Thomas Edward Watson

10. Notes on the Case of Leo M. Frank, By Tom W. Brown, Emery University, Atlanta, Georgia, 1982.

Leo Frank Georgia Supreme Court Archive:

11. Leo Frank Trial and Appeals Georgia Supreme Court File (1,800 pages). http://archive.org/details/leo-frank-georgia-supreme-court-case-records-1913-1914

* * *

For further information, check out the full American Mercury series on the Leo Frank case by clicking here.