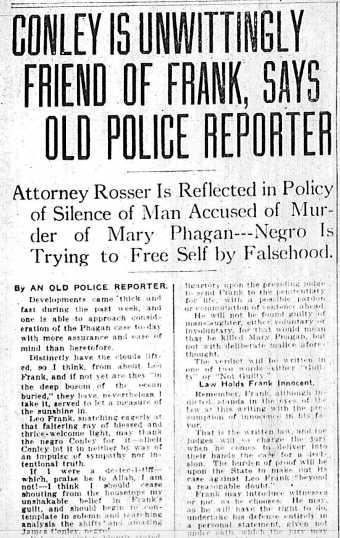

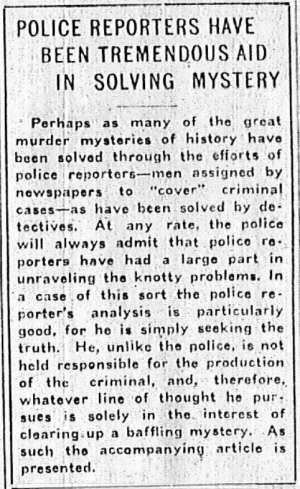

Another in our series of new transcriptions of contemporary articles on the Leo Frank case.

Another in our series of new transcriptions of contemporary articles on the Leo Frank case.

Atlanta Georgian

Sunday, June 1st, 1913

By AN OLD POLICE REPORTER.

Developments came thick and fast during the past week, and one is able to approach consideration of the Phagan case to-day with more assurance and ease of mind than heretofore.

Distinctly have the clouds lifted, so I think, from about Leo Frank, and if not yet are they “in the deep bosom of the ocean buried,” they have, nevertheless I take it, served to let a measure of the sunshine in.

Leo Frank, snatching eagerly at that faltering ray of blessed and thrice-welcome light, may thank the negro Conley for it—albeit Conley let it in neither by way of an impulse of sympathy nor intentional truth.

If I were a de-tec-i-tiff—which, praise be to Allah, I am not!—I think I should cease shouting from the housetops my unshakable belief in Frank’s guilt, and should begin to contemplate in solemn and searching analysis the shifty and amazing James Conley, negro!

It is my opinion, bluntly stated, that Conley is an unmitigated liar, all the way through, and that the truth is not in him!

His statement appeals to me an Old Police Reporter—and not a de-tec-i-tiff, again praise be to Allah!—as distinctly the weightiest document in Leo Frank’s favor that yet has been promulgated.

Would Belong in Asylum.

Certainly, if Frank DID do the astonishing things Conley attributes to him, he should not be sent to the gallows, in any event, for he surely belongs in Milledgeville, safely held in the State lunatic asylum. But, more of Conley hereafter. The issue of murder has been made with Leo Frank, and he must face trial. The Grand Jury has indicted him, and he will be arraigned in due time and in order.

It will be a finish fight between the State and the defendant. There can be no compromise now—either Frank is guilty or he is innocent, and the truth of that is for twelve men, “good and true,” to say.

They will be picked carefully, the State and the defense each exercising its right of elimination to the limit, no doubt, in seeking to frame a jury likely to hand in a just verdict. At least, that is the theory of it.

Solomon cited three strange things as the strangest of all things—the way of an eagle in the air, a serpent upon a rock, and a man with a maid.

Jury Strangest of All.

In Solomon’s day, however, they did not have trials by jury, otherwise I feel sure his majesty would have added the way of a jury with a defendant as the fourth exceeding strange thing.

The wind bloweth where it listeth, and no man knoweth whence it cometh or whither it goeth—and by the same token, the verdicts of juries are past prophecy and sure anticipation.

Therefore, students of the uncertain—those people who delight to indulge in speculation and baffling forethought—have three puzzles to engage their minds.

First, who killed Mary Phagan? Second, what will Frank’s defense be? Third, what will the jury say?

One thing seems certain, either the jury will acquit Frank utterly or condemn him utterly.

There will be no recommendation of mercy, if he is found guilty, for that would make it obligatory upon the presiding judge to send Frank to the penitentiary for life, with a possible pardon or commutation of sentence ahead.

He will not be found guilty of manslaughter, either voluntary or involuntary, for that would mean that he killed Mary Phagan, but not with deliberate malice aforethought.

The verdict will be written in one of two words—either “Guitly” or “Not Guilty.”

Law Holds Frank Innocent.

Remember Frank, although indicted, stands in the eyes of the law at this writing with the presumption of innocence in his favor.

That is the written law, and the judges will so charge the jury when he comes to deliver into their hands the case for a decision. The burden of proof will be upon the State to make out its case against Leo Frank “beyond a reasonable doubt.”

Frank may introduce witnesses or not, as he chooses. He may, as he will have the right to do, undertake his defense entirely in a personal statement, given not under oath, which the jury may accept in whole or in part, or reject in whole or in part, and to the exclusion of all the sworn testimony, if it so elects.

That also is the written law, and the trial jury will be so charged.

The State of Georgia is very fair to a defendant, fairer than many States.

If Frank should elect to rely upon his own statement alone, it will indicate his firm faith in the weakness of the State’s case against him, and a determination to risk his chances thereup. To that extent, therefore, it would be calculated to affect the jury favorably to his point of view.

Point Favors Rosser.

Moreover, such a course would give that wonderful criminal lawyer, Luther Z. Rosser, both the opening and concluding argument before the jury, which otherwise he will forfeit to the State—and that in a case of the Phagan character, is a matter of possibly tremendous consequence.

It will not surprise me if Luther Rosser takes his time about assembling the jury to try Frank, in so far as he may. Neither will it surprise me to see him exhaust every effort to get a jury of marked intelligence.

I think he will incline to secure as many high-class men upon it as possible—conservative businessmen, heads of families, non-emotional, middle-aged persons, perhaps a minister of the gospel.

Here is a case of nation-wide interest. Not only is Leo Frank to be put on trial; the State of Georgia is to be put on trial also!

Of absorbing interest now, of course, is the probable theory of Frank’s defense.

I have some ideas with regard to what it may be, and these I state, merely for what they may be worth, and as matters of personal speculation purely.

What I say of the defense is not said to prejudice the case one way or another. I have no personal concern in it whatever—it interests me merely in the abstract. I have no acquaintance or connection with any party to the tragedy of Mary Phagan—not the slightest. It is, to me, an absorbing problem—that’s all.

Murder is the unlawful killing of a human being in the peace of that State, with malice aforethought, either expressed or implied. It may be proved either by direct or circumstantial evidence.

Naturally, it is harder to make out a case of murder by circumstantial evidence alone than by direct or mixed evidence.

Will the State of Georgia be able to make out such a definite case against Frank that the State will be willing to take his life upon the gallows as a forfeit for his crime? It either is that, or acquittal.

No Definite Responsibility.

Prophecy is gratuitous in matters of this kind, of course, and venturesome, but inasmuch as I am speaking for myself alone, I think I shall go on record here and now as saying that THE STATE NEVER WILL FIX UPON LEO FRANK DEFINITE RESPONSIBILITY FOR MARY PHAGAN’S MURDER!

I do not believe the State’s case—unless its most convincing elements yet are secret—will “stand up” in court to that degree necessary for conviction.

And with no hint or suggestion from him to guide my mind or direct its trend, I predict that Luther Z. Rosser will bend his best energies to showing more the hopeless weakness of the State’s case than the strength of Frank’s defense. He will, I think, seek to clear Frank largely through a process of elimination directed at the various factors in the case set up against him.

He will put in fearful and full measure the tremendous responsibility upon the State of taking Frank’s life without being very sure of his guilt.

And that argument, remember, is to be directed not to YOU, gentle reader, nor to ME, nor to the judge, nor to the spectators in the court house—but to those TWELVE MEN “good and true,” under oath to do justice, there in the jury box!

Must Remember Law’s Majesty.

Luther Rosser is going to demand of that jury that it remember the majesty of the law—and he is going to picture its greatest majesty in its protection of the innocent rather than in its punishment of the guilty.

Let us now consider for a while the part the negro Conley is playing in this Phagan case.

Conley’s participation began with a lie. He first ventured the assertion, vehemently, that he could not write. It was soon discovered that the negro was falsifying about that.

He next swears that he wrote the notes found beside Mary Phagan’s dead body, and that he wrote them the day BEFORE the killing. Presumably, it finally filtered through his thick head that he had made out a case of premeditated murder against Frank in that statement—if he had made out any case at all—and so he shifted away and again swore that he wrote the notes the day OF the killing!

Finally, he gave out a statement, sworn to again—he seems to be about the most willing swearer that ever came down the pike!—saying that he actually had helped Frank, AT FRANK’S INVITATION, somewhat difficultly delivered, to dispose of the dead body of Mary Phagan, penned the notes at Frank’s dictation, and ALMOST GOT $200 FOR DOING IT!

Do you believe the moon, “the pale, inconstant moon, that nightly changes,” is made of green cheese, gentle reader? If so, it may so happen that you believe Conley is telling the truth—otherwise, I doubt it.

Frank in Conley’s Hands.

Look at it in a common-sense light. Look at it fairly and squarely. Face it in its abstract aspect.

Ask yourself this question: Would Leo Frank, a white man of at least average intelligence and good reputation, with a family at home and a good business standing abroad, kill a girl just in her teens, sure in the knowledge that no human being had witnessed the deed, and then deliberately go forth to find a shiftless negro to make him directly acquainted with the crime and its circumstances, and that to hide a body as effectively hidden as it was when found next morning?

Did Leo Frank do that? If so, he is not a murderer in any—event—he is an irresponsible lunatic! And it doesn’t occur to me as remotely possible that Mr. Rosser will enter a plea of lunacy in Frank’s behalf.

What is there, outside the preposterous “confession” of Conley that might be damaging to Frank that he has not himself been first to admit?

Did Frank not admit, readily, being in the pencil factory at such and such hours, held to suggest the possibility of his having committed the crime? Did he not say, voluntarily, when shown the dead body of Mary Phagan, “Why, that is one of the girls I paid-of yesterday?”

Has Frank dodged and shifted and given out contradictory statements since he was taken in charge by the police?

He has not. On the contrary, such things as he has said have borne the earmarks of naturalness and poise—and of truth.

Contrast that with the almost ludicrous, though grim, tissue of falsehoods Conley has spun from the very beginning.

No Doubt About Notes.

There is no reasonable doubt that Conley wrote the notes—the only possible doubt as to that, it seems to me, is that Conley “confesses” that he wrote them.

One can hardly suppress a smile, of course, when he recalls how the “experts” primarily opined that Newt Lee’s handwriting was mightily like the writing in the notes—but let that pass. This Phagan case is a tragedy, and not a comedy—except in infrequent spots.

Will Conley be indicted as an accessory to the murder of Mary Phagan? If he is, how will the State corroborate him, as it must in that event?

And yet, if this statement is true, or if the authorities believe is to be true, certainly he IS an accessory.

Shreds and patches will be about the proper words to employ in discussing Conley when Luther Rosser gets through with him, I suspect.

If the suddenly grown loquacious Conley only can be kept loquacious, we yet may reach the absolute truth of the Phagan murder, before Frank goes to trial!

Looking back over the articles I heretofore have written with respect to the Phagan case, and noting the thread of more or less unconscious optimism as concerns the final intent of the people to be fair, to be just, to be true to their higher ideals, I note little if anything, that I would unsay.

Public Opinion Honest.

Public opinion yields readily enough now and then to passionate impulse and unreason, but, in the long run, it may be depended upon to right itself and to deal honestly with men and things.

I thought I was right in saying that judgment some time ago was suspended with regard to Leo Frank, that the public mind, free of its initial distortion, had settled itself into a calm determination to see fair play—fair play for all, for Frank, for the dead girl and for the great State of Georgia.

I thought I was right in saying that judgment some time ago was suspended with regard to Leo Frank, that the public mind, free of its initial distortion, had settled itself into a calm determination to see fair play—fair play for all, for Frank, for the dead girl and for the great State of Georgia.

To-day I think the public mind is more firmly set in that direction than ever. The people of Atlanta, of Georgia, of the South, of the nation ARE FAIR!

One or two further points, and I am through.

There are those who wonder why Frank, innocent, if so he be, so persistently declines to see people and to discuss his case for the public edification. In the first place, I may answer to that, Frank has employed for his defense the most discreet and secretive attorney in Atlanta, Luther Rosser is and ever has been, the personification of silence when silence seemed golden. In the matter of keeping things to himself, the well known Sphynx has nothing whatever on Luther Z. Rosser. Mr. Rosser unquestionably long ago advised Frank not to talk—particularly when he (Rosser) was at Tallulah Falls trying a case. Besides, by declining to try his case in the newspapers, Frank has displayed much common sense.

Conley Badly Frightened.

There are those who ask why Conley confessed, when to keep quiet seemed so much safer.

Well, Conley is a negro, and he started out with a stupid purpose to lie—remember his denial of his ability to write—and when he found that he was being suspected, despite his lies, he became fearful that suspicion would shift from Frank to himself, and so he rushed forth to fix it upon Frank in so far as he might. He has had four weeks to frame his story in his mind and to rehearse it to himself. He has rehearsed it to himself so many times, that, negro like, he actually may believe it, or at least part of it.

And I doubt capitally that he is through talking—and swearing—yet!

There are two possible outcomes of the Phagan case that are interesting to think upon.

First, the indictment against Frank may be set aside because of the charge of strangulation therein set up. To dispose of the case after that fashion, however, would hardly leave Frank as clear as he undoubtedly must wish to come, if he is innocent—and, therefore, I do not believe that defense will be entered.

Again, a mistrial may result, is not so unlikely as the other thing—but a mistrial is rated in legal parlance as “a half acquittal.” It merely would postpone the final disposition of the charge.

Well, every fellow to his own taste, as the old lady said when she kissed her cow in preference to her old man. As for me, I believe the State is further from a conviction of Leo Frank to-day than it ever has been—and rightly so.

* * *

Atlanta Georgian, June 1st 1913, “Conley is Unwittingly Friend of Frank, Says Old Police Reporter,” Leo Frank case newspaper article series (Original PDF)