Another in our series of new transcriptions of contemporary articles on the Leo Frank case.

Another in our series of new transcriptions of contemporary articles on the Leo Frank case.

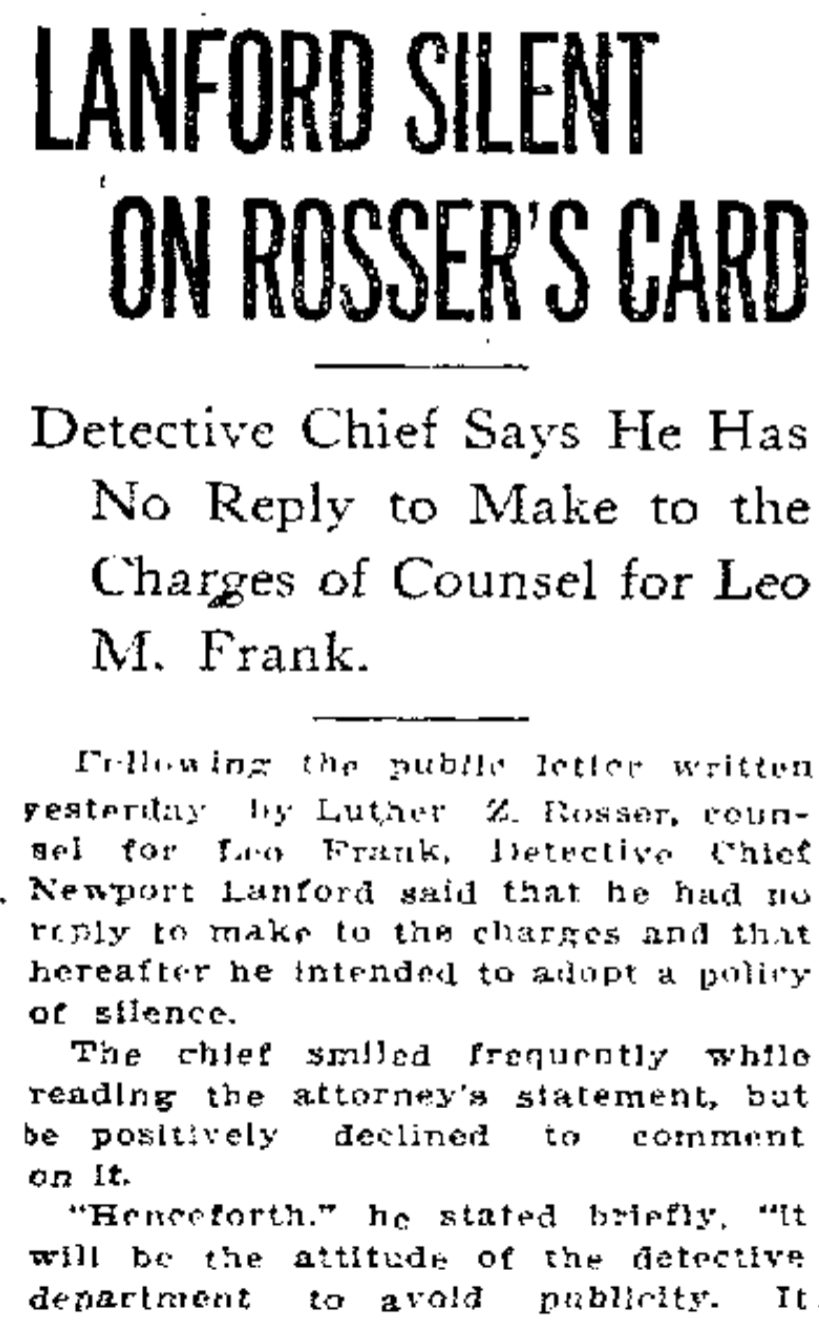

The Atlanta Constitution

June 11, 1913

Detective Chief Says He Has No Reply to Make to the Charges of Counsel for Leo M. Frank.

Following the public letter written yesterday by Luther Z. Rosser, counsel for Leo Frank, Detective Chief Newport Lanford said that he had no reply to make to the charges and that hereafter he intended to adopt a policy of silence.

The chief smiled frequently while reading the attorney’s statement, but be positively declined to comment on it.

“Henceforth,” he stated briefly, “It will be the attitude of the detective department to avoid publicity. It should have been done heretofore.”

Lanford declared that Rosser’s card is only an attempt to draw the detective chief into a newspaper controversy, which he intended to avert.

“It is all a scheme—nothing else,” he said, “and I do not propose to be made a victim.”

The statement of Frank’s counsel is a scathing arraignment of Chief Lanford and his department for alleged efforts to prove guilty a white man, against whom prejudice had been created, through the “lying” stories of a negro, against whom all “legitimate” suspicion already was directed.

It follows:

Mr. Rosser’s Statement.

Editor, Atlanta Constitution: Felder and Lanford, in an effort to make progress in their feud, charge each other with giving aid to Leo Frank. Lanford charges that Felder was employed by Frank and is seeking for that reason to shield him. Felder charges Lanford and his associates are also seeking, for some reason, to shield and protect Frank.

Both charges are untrue and, at a time when no harm could come to an innocent man, might well be treated antidotes to monotony.

Unfortunately, however, the present situation is such that fair-minded citizens may be misled by these counter charges.

Felder does not, nor has he at any time, directly or indirectly, represented Frank. For Lanford to charge the contrary does Frank a serious injustice.

Felder Against Frank.

If Chief Lanford had been in a sane, normal mood, he would have known that every act of Felder has been against Frank. The engagement of the Burns agency ought to have satisfied Lanford. No detective agency of half prudence would have double-crossed the Atlanta department in the Phagan case. Nor did Felder have excuse for suspicion against Lanford. There was reason to suspect his fairness, his accuracy and the soundness of his methods, but not his reckless zeal against Frank.

Had Felder been in a calm mood I am sure he would never have charged the chief and his associates with intention to help Frank.

Lanford at once, as soon as Felder charged him with favoring Frank, settled in his mind the guilt of Frank, and from that monent has bent every energy of his department, not in finding the murderer, but in trying to prove to the public that Felder was wrong in charging him with trying to shield Frank.

Leo Frank’s Past.

His department has exhausted itself in an effort to fix upon Frank an immoral life, on the theory that a violator of the seventh commandment was likewise a murderer. This effort has failed. No man in Atlanta has had his moral character subjected to such a test and there is not in the whole city of Atlanta a half dozen men who could have more successfully stood the test.

His employees, without a single exception, have made affidavits to his uprightness. Lanford’s department subpoenaed every one of them before the coroner’s jury, and after keeping them more than two days did not dare to swear a single one of them.

Before and after the coroner’s verdict this whole city has been combed with a fine tooth comb and a like combing has been applied to Brooklyn, the city of his birth, to find something against his moral character. With what result? The silence of the detective department gives the answer.

“Drivel and Nonsense.”

Lanford’s conduct in connection wtih the woman Formby and the negro Conley shows that he was stung by Felder’s charge that he was favoring Frank, or that for some other reason he was temporarily out of his head.

He swallowed whole the statements of this Formby woman, bearing upon their face the clear proof that they were by no means to be believed.

This woman was not unknown to Lanford. She did not entrap him by appearing under the guise of a truthful, sober virtuous woman. But so absorbed was he, either in trying to disprove Felder’s charge or in the foolish pride of opinion that he accepted without doubt or fair investigation the drived and nonsense of this woman.

So far beside himself did he become that he had the folly to furnish to the papers, based upon this woman’s statement, the theory that Frank, during the night of the murder, wishing to rid himself of the body, was seeking to do so in a room rented from this woman.

The folly and difficulties of the theory did not disturb Lanford. They would have disturbed anybody but Lanford. His insane desire to justify himself cleared the matter of all difficulties and follies.

Conley an Ignorant Negro.

If the case of the Formby woman did not clear Lanford of Felder’s charge, that of the Conley negro ought to have done so.

Conley is a very ordinary, ignorant, brutal negro, not unacquainted with the stockade. His actions immediately after the crime were suspicious. So much so that they attracted the attention of the employees of the factory and occasioned general comment. In spite of these facts, Conley was not taken into custody until several days after the crime and not then until the employees of the factory caught him suspiciously washing a shirt and as a result reported him to the police. He was not brought before the coroner’s jury and practically no notice was taken of him in that investigation. So swiftly was Lanford and his associates pursuing Frank that they ran over this negro, standing in their path with the marks of guilt clearly upon him.

Finally, the pressure of public suspicion brought this negro to Lanford’s attention. Conley began to talk and negro-like to talk so as to protect himself and as a means thereto to cast suspicion upon some one else. Ordinarily the detectives could be trusted not to aid the negro in an effort to clear himself by placing the crime on a white man, but in this case it is to be feared that the negro was not discouraged. Lanford had finally banked all his sense, all his reputation as a man and a politician upon Frank’s guilt and it would be remarkable if the discouraged this negro from involving Frank. If Lanford and his followers had acted wisely, and kept open minds seeking only the murderer and not seeking to vindicate their announced opinions the negro would have by this hold the whole truth.

Conley made one statement. It did not meet the announced opinions of Lanford. He made another. This second was not up to the mark, it did not sufficiently show Frank’s guilt. Another was made, which was supposed to be nearer the mark. Whereupon there was great rejoicing. Forgetting all others, this last statement—reached through such great tribulations—was proclaimed the truth, the last truth and that there would be no other statement.

The detectives had at last got the statement which they thought sustained their views, saved their reputations and insured their places.

Full of Contradictions.

But what a statement! So full of contradictions, so evidently made for self protection and wherein was so easily apparent the guiding hand of detectives. If Lanford meant to be fair, if was only seeking the truth, why did he rush into print with the assertion that this statement was the truth and therefore of necessity the last? Might he not in decency have left this negro to his own will unbiased by the opinion that the statement was true and the last to be given? Who knows but that this negro might have given numerous other statements if he had not been so heavily handicapped by Lanford’s opinion.

The truth is this negro is not to give any other or further statement if the detective department can prevent, unless made under their supervision and direction. He must, at all times, be under the influence and control of Lanford. He must have Lanford’s sucking bottle at all times to his lips, sucking Lanford’s views and theories of this case. The ragged places in his statement must be darned, the torn places patched and no one but the detective department could be trusted to do that.

Thinks Conley Guilty.

No one has been rude enough to bring this negro before the grand jury nor indeed to make any charge against him.

After the statement of this negro and in view of all the evidence which so strongly points to him as the slayer of little Mary Phagan, is the grand jury to leave him without charge or investigation to be wet nursed by Lanford until Frank’s trial?

Or is it the purpose to keep the negro’s case from the grand jury in the nature of an offered reward to spur him on to swear his worst against the white man?

Would it not be just and decent to bring this negro’s case before the grand jury and let that body hear his confession so that it can then decide whether the negro should then be indicted?

In the shadow of this great crime let there be no thimble-ringing; let no single fact be concealed; let no man’s place or reputation stand in the way of the fullest, fairest investigation.

Respectfully,

(Signed) LUTHER Z. ROSSER.

* * *