American Dissident Voices broadcast of August 15, 2015

by Kevin Alfred Strom

MORE THAN 100 YEARS AGO, Jewish sweatshop operator Leo Max Frank was executed by hanging for the crime of murdering a 13-year-old girl employee of his, Mary Phagan (pictured). Some have called the hanging a lynching, but was it? It was not carried out by an undisciplined mob, but by a citizens’ militia, who, with military precision — and commanded by eminent men, leaders of their community — removed Frank from his cell and carried out the sentence of the court. These men were outraged that Frank’s sentence had been overturned by an outgoing governor not only in the pay of wealthy Jews but actually a partner in the law firm that defended Frank. The militia men did not believe in mob rule — far from it. But they felt they had no alternative but to take the decision to carry out the jury’s sentence out of the hands of a corrupt governor and into their own. Why? What made these men so certain of Frank’s guilt, when today all we hear from the controlled media is that he was innocent, innocent, innocent?

Today you’re going to find out. We now present the new audio book by Vanessa Neubauer, based on the series published in the American Mercury by Bradford L. Huie. On the 100th anniversary of the death of Leo Frank, we offer you “100 Reasons Leo Frank is Guilty.” I give you Miss Vanessa Neubauer:

* * *

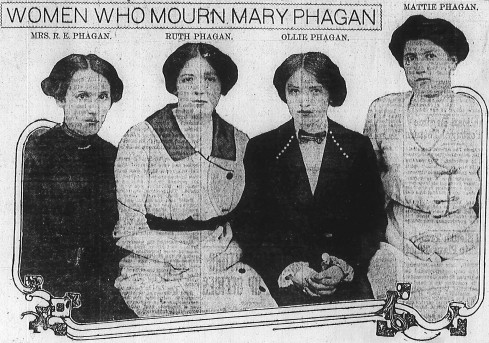

MARY PHAGAN was just thirteen years old. She was a sweatshop laborer for Atlanta, Georgia’s National Pencil Company. Exactly 100 years ago today — Saturday, April 26, 1913 — little Mary (pictured, artist’s depiction) was looking forward to the festivities of Confederate Memorial Day. She dressed gaily and planned to attend the parade. She had just come to collect her $1.20 pay from National Pencil Company superintendent Leo M. Frank at his office when she was attacked by an assailant who struck her down, ripped her undergarments, likely attempted to sexually abuse her, and then strangled her to death. Her body was dumped in the factory basement.

Leo Frank, who was the head of Atlanta’s B’nai B’rith, a Jewish fraternal order, was eventually convicted of the murder and sentenced to hang. After a concerted and lavishly financed campaign by the American Jewish community, Frank’s death sentence was commuted to life in prison by an outgoing governor. But he was snatched from his prison cell and hung by a lynching party consisting, in large part, of leading citizens outraged by the commutation order — and none of the lynchers were ever prosecuted or even indicted for their crime. One result of Frank’s trial and death was the founding of the still-powerful Anti-Defamation League.

Today Leo Frank’s innocence, and his status as a victim of anti-Semitism, are almost taken for granted. But are these current attitudes based on the facts of the case, or are they based on a propaganda campaign that began 100 years ago? Let’s look at the facts.

It has been proved beyond any shadow of doubt that either Leo Frank or National Pencil Company sweeper Jim Conley was the killer of Mary Phagan. Every other person who was in the building at the time has been fully accounted for. Those who believe Frank to be innocent say, without exception, that Jim Conley must have been the killer.

On the 100th anniversary of the inexpressibly tragic death of this sweet and lovely girl, let us examine 100 reasons why the jury that tried him believed (and why we ought to believe, once we see the evidence) that Leo Max Frank strangled Mary Phagan to death — 100 reasons proving that Frank’s supporters have used multiple frauds and hoaxes and have tampered with the evidence on a massive scale — 100 reasons proving that the main idea that Frank’s modern defenders put forth, that Leo Frank was a victim of anti-Semitism, is the greatest hoax of all.

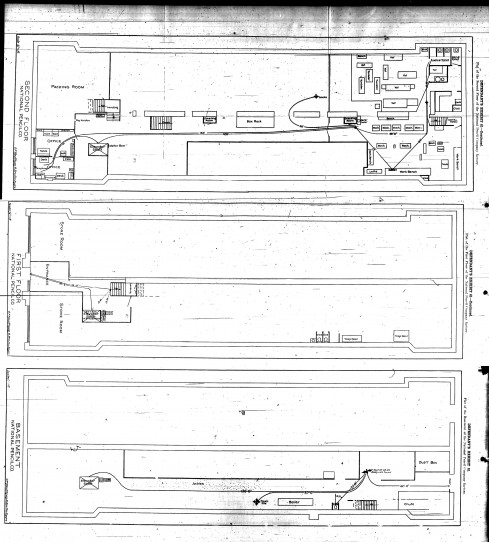

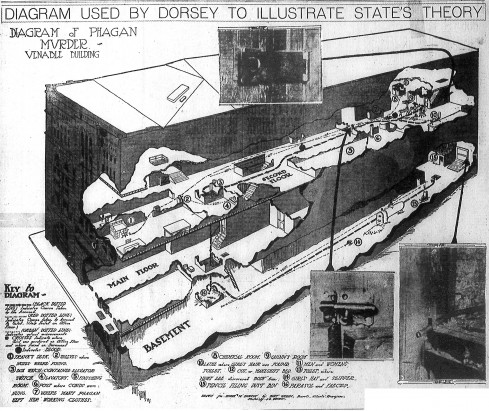

1. Only Leo Frank had the opportunity to be alone with Mary Phagan, and he admits he was alone with her in his office when she came to get her pay — and in fact he was completely alone with her on the second floor. Had Jim Conley been the killer, he would have had to attack her practically right at the entrance to the building where he sat almost all day, where people were constantly coming and going and where several witnesses noticed Conley, with no assurance of even a moment of privacy.

2. Leo Frank had told Newt Lee, the pencil factory’s night watchman, to come earlier than usual, at 4 PM, on the day of the murder. But Frank was extremely nervous when Lee arrived (the killing of Mary Phagan had occurred between three and four hours before and her body was still in the building) and insisted that Lee leave and come back in two hours.

3. When Lee then suggested he could sleep for a couple of hours on the premises — and there was a cot in the basement near the place where Lee would ultimately find the body — Frank refused to let him. Lee could also have slept in the packing room adjacent to Leo Frank’s office. But Frank insisted that Lee had to leave and “have a good time” instead. This violated the corporate rule that once the night watchman entered the building, he could not leave until he handed over the keys to the day watchman. Newt Lee, though strongly suspected at first, was manifestly innocent and had no reason to lie, and had had good relations with Frank and no motive to hurt him.

4. When Lee returned at six, Frank was even more nervous and agitated than two hours earlier, according to Lee. He was so nervous, he could not operate the time clock properly, something he had done hundreds of times before. (Leo Frank officially started to work at the National Pencil Company on Monday morning, August 10, 1908. Twenty-two days later, on September 1, 1908, he was elevated to the position of superintendent of the company, and served in this capacity until he was arrested on Tuesday morning, April 29, 1913.)

5. When Leo Frank came out of the building around six, he met not only Lee but John Milton Gantt, a former employee who was a friend of Mary Phagan. Lee says that when Frank saw Gantt, he visibly “jumped back” and appeared very nervous when Gantt asked to go into the building to retrieve some shoes that he had left there. According to E.F. Holloway, J.M. Gantt had known Mary for a long time and was one of the only employees Mary Phagan spoke with at the factory. Gantt was the former paymaster of the firm. Frank had fired him three weeks earlier, allegedly because the payroll was short about $1. Was Gantt’s firing a case of the dragon getting rid of the prince to get the princess? Was Frank jealous of Gantt’s closeness with Mary Phagan? Unlike Frank, Gantt was tall with bright blue eyes and handsome features.

6. After Frank returned home in the evening after the murder, he called Newt Lee on the telephone and asked him if everything was “all right” at the factory, something he had never done before. A few hours later Lee would discover the mutilated body of Mary Phagan in the pencil factory basement.

7. When police finally reached Frank after the body of Mary Phagan had been found, Frank emphatically denied knowing the murdered girl by name, even though he had seen her probably hundreds of times — he had to pass by her work station, where she had worked for a year, every time he inspected the workers’ area on the second floor and every time he went to the bathroom — and he had filled out her pay slip personally on approximately 52 occasions, marking it with her initials “M. P.” Witnesses also testified that Frank had spoken to Mary Phagan on multiple occasions, even getting a little too close for comfort at times, putting his hand on her shoulder and calling her “Mary.”

8. When police accompanied Frank to the factory on the morning after the murder, Frank was so nervous and shaking so badly he could not even perform simple tasks like unlocking a door.

9. Early in the investigation, Leo Frank told police that he knew that J.M. Gantt had been “intimate” with Mary Phagan, immediately making Gantt a suspect. Gantt was arrested and interrogated. But how could Frank have known such a thing about a girl he didn’t even know by name?

10. Also early in the investigation, while both Leo Frank and Newt Lee were being held and some suspicion was still directed at Lee, a bloody shirt was “discovered” in a barrel at Lee’s home. Investigators became suspicious when it was proved that the blood marks on the shirt had been made by wiping it, unworn, in the liquid. The shirt had no trace of body odor and the blood had fully soaked even the armpit area, even though only a small quantity of blood was found at the crime scene. This was the first sign that money was being used to procure illegal acts and interfere in the case in such a way as to direct suspicion away from Leo M. Frank. This became a virtual certainty when Lee was definitely cleared.

11. Leo Frank claimed that he was in his office continuously from noon to 12:35 on the day of the murder, but a witness friendly to Frank, 14-year-old Monteen Stover, said Frank’s office was totally empty from 12:05 to 12:10 while she waited for him there before giving up and leaving. This was approximately the same time as Mary Phagan’s visit to Frank’s office and the time she was murdered. On Sunday, April 27, 1913, Leo Frank told police that Mary Phagan came into his office at 12:03 PM. The next day, Frank made a deposition to the police, with his lawyers present, in which he said he was alone with Mary Phagan in his office between 12:05 and 12:10. Frank would later change his story again, stating on the stand that Mary Phagan came into his office a full five minutes later than that.

12. Leo Frank contradicted his own testimony when he finally admitted on the stand that he had possibly “unconsciously” gone to the Metal Room bathroom between 12:05 and 12:10 PM on the day of the murder.

13. The Metal Room, which Frank finally admitted at trial he might have “unconsciously” visited at the approximate time of the killing (and where no one else except Mary Phagan could be placed by investigators), was the room in which the prosecution said the murder occurred. It was also where investigators had found spots of blood, and some blondish hair twisted on a lathe handle — where there had definitely been no hair the day before. (When R.P. Barret left work on Friday evening at 6:00 PM, he had left a piece of work in his machine that he intended to finish on Monday morning at 6:30 AM. It was then he found the hair — with dried blood on it — on his lathe. How did it get there over the weekend, if the factory was closed for the holiday? Several co-workers testified the hair resembled Mary Phagan’s. Nearby, on the floor adjacent to the Metal Room’s bathroom door, was a five-inch-wide fan-shaped blood stain.)

14. In his initial statement to authorities, Leo Frank stated that after Mary Phagan picked up her pay in his office, “She went out through the outer office and I heard her talking with another girl.” This “other girl” never existed. Every person known to be in the building was extensively investigated and interviewed, and no girl spoke to Mary Phagan nor met her at that time. Monteen Stover was the only other girl there, and she saw only an empty office. Stover was friendly with Leo Frank, and in fact was a positive character witness for him. She had no reason to lie. But Leo Frank evidently did. (Atlanta Georgian, April 28, 1913)

15. In an interview shortly after the discovery of the murder, Leo Frank stated “I have been in the habit of calling up the night watchman to keep a check on him, and at 7 o’clock called Newt.” But Newt Lee, who had no motive to hurt his boss (in fact quite the opposite) firmly maintained that in his three weeks of working as the factory’s night watchman, Frank had never before made such a call. (Atlanta Georgian, April 28, 1913)

16. A few days later, Frank told the press, referring to the National Pencil Company factory where the murder took place, “I deeply regret the carelessness shown by the police department in not making a complete investigation as to finger prints and other evidence before a great throng of people were allowed to enter the place.” But it was Frank himself, as factory superintendent, who had total control over access to the factory and crime scene — who was fully aware that evidence might thereby be destroyed — and who allowed it to happen. (Atlanta Georgian, April 29, 1913)

17. Although Leo Frank made a public show of support for Newt Lee, stating Lee was not guilty of the murder, behind the scenes he was saying quite different things. In its issue of April 29, 1913, the Atlanta Georgian published an article titled “Suspicion Lifts from Frank,” in which it was stated that the police were increasingly of the opinion that Newt Lee was the murderer, and that “additional clews furnished by the head of the pencil factory [Frank] were responsible for closing the net around the negro watchman.” The discovery that the bloody shirt found at Lee’s home was planted, along with other factors such as Lee’s unshakable testimony, would soon change their views, however.

18. One of the “clews” provided by Frank was his claim that Newt Lee had not punched the company’s time clock properly, evidently missing several of his rounds and giving him time to kill Mary Phagan and return home to hide the bloody shirt. But that directly contradicted Frank’s initial statement the morning after the murder that Lee’s time slip was complete and proper in every way. Why the change? The attempt to frame Lee would eventually crumble, especially after it was discovered that Mary Phagan died shortly after noon, four hours before Newt Lee’s first arrival at the factory.

19. Almost immediately after the murder, pro-Frank partisans with the National Pencil Company hired the Pinkerton detective agency to investigate the crime. But even the Pinkertons, being paid by Frank’s supporters, eventually were forced to come to the conclusion that Frank was the guilty man. (The Pinkertons were hired by Sigmund Montag of the National Company at the behest of Leo Frank, with the understanding that they were to “ferret out the murderer, no matter who he was.” After Leo Frank was convicted, Harry Scott and the Pinkertons were stiffed out of an investigation bill totaling some $1300 for their investigative work that had indeed helped to “ferret out the murderer, no matter who he was.” The Pinkertons had to sue to win their wages and expenses in court, but were never able to fully collect. Mary Phagan’s mother also took the National Pencil Company to court for wrongful death, and the case settled out of court. She also was never able to fully collect the settlement. These are some of the unwritten injustices of the Leo Frank case, in which hard-working and incorruptible detectives were stiffed out of their money for being incorruptible, and a mother was cheated of her daughter’s life and then cheated out of her rightful settlement as well.) (Atlanta Georgian, May 26, 1913, “Pinkerton Man says Frank Is Guilty – Pencil Factory Owners Told Him Not to Shield Superintendent, Scott Declares”)

20. That is not to say that were not factions within the Pinkertons, though. One faction was not averse to planting false evidence. A Pinkerton agent named W.D. McWorth — three weeks after the entire factory had been meticulously examined by police and Pinkerton men — miraculously “discovered” a bloody club, a piece of cord like that used to strangle Mary Phagan, and an alleged piece of Mary Phagan’s pay envelope on the first floor of the factory, near where the factory’s Black sweeper, Jim Conley, had been sitting on the fatal day. This was the beginning of the attempt to place guilt for the killing on Conley, an effort which still continues 100 years later. The “discovery” was so obviously and patently false that it was greeted with disbelief by almost everyone, and McWorth was pulled off the investigation and eventually discharged by the Pinkerton agency.

21. It also came out that McWorth had made his “finds” while chief Pinkerton investigator Harry Scott was out of town. Most interestingly, and contrary to Scott’s direct orders, McWorth’s “discoveries” were reported immediately to Frank’s defense team, but not at all to the police. A year later, McWorth surfaced once more, now as a Burns agency operative, a firm which was by then openly working in the interests of Frank. One must ask: Who would pay for such obstruction of justice? — and why? (Frey, The Silent and the Damned, page 46; Indianapolis Star, May 28, 1914; The Frank Case, Atlanta Publishing Co., p. 65)

22. Jim Conley told police two obviously false narratives before finally breaking down and admitting that he was an accessory to Leo Frank in moving of the body of Mary Phagan and in authoring, at Frank’s direction, the “death notes” found near the body in the basement. These notes, ostensibly from Mary Phagan but written in semi-literate Southern black dialect, seemed to point to the night watchman as the killer. To a rapt audience of investigators and factory officials, Conley re-enacted his and Frank’s conversations and movements on the day of the killing. Investigators, and even some observers who were very skeptical at first, felt that Conley’s detailed narrative had the ring of truth.

23. At trial, the leading — and most expensive — criminal defense lawyers in the state of Georgia could not trip up Jim Conley or shake him from his story.

24. Conley stated that Leo Frank sometimes employed him to watch the entrance to the factory while Frank “chatted” with teenage girl employees upstairs. Conley said that Frank admitted that he had accidentally killed Mary Phagan when she resisted his advances, and sought his help in the hiding of the body and in writing the black-dialect “death notes” that attempted to throw suspicion on the night watchman. Conley said he was supposed to come back later to burn Mary Phagan’s body in return for $200, but fell asleep and did not return.

25. Blood spots were found exactly where Conley said that Mary Phagan’s lifeless body was found by him in the second floor metal room.

26. Hair that looked like Mary Phagan’s was found on a Metal Room lathe immediately next to where Conley said he found her body, where she had apparently fallen after her altercation with Leo Frank.

27. Blood spots were found exactly where Conley says he dropped Mary Phagan’s body while trying to move it. Conley could not have known this. If he was making up his story, this is a coincidence too fantastic to be accepted.

28. A piece of Mary Phagan’s lacy underwear was looped around her neck, apparently in a clumsy attempt to hide the deeply indented marks of the rope which was used to strangle her. No murderer could possibly believe that detectives would be fooled for an instant by such a deception. But a murderer who needed another man’s help for a few minutes in disposing of a body might indeed believe it would serve to briefly conceal the real nature of the crime from his assistant, perhaps being mistaken for a lace collar.

29. If Conley was the killer — and it had to be Conley or Frank — he moved the body of Mary Phagan by himself. The lacy loop around Mary Phagan’s neck would serve absolutely no purpose in such a scenario.

30. The dragging marks on the basement floor, leading to where Mary Phagan’s body was dumped near the furnace, began at the elevator — exactly matching Jim Conley’s version of events.

31. Much has been made of Conley’s admission that he defecated in the elevator shaft on Saturday morning, and the idea that, because the detectives crushed the feces for the first time when they rode down in the elevator the next day, Conley’s story that he and Frank used the elevator to bring Mary Phagan’s body to the basement on Saturday afternoon could not be true — thus bringing Conley’s entire story into question. But how could anyone determine with certainty that the “crushing” was the “first crushing”? And nowhere in the voluminous records of the case — including Governor Slaton’s commutation order in which he details his supposed tests of the elevator — can we find evidence that anyone made even the most elementary inquiry into whether or not the bottom surface of the elevator car was uniformly flat.

32. Furthermore, the so-called “shit in the shaft” theory of Frank’s innocence also breaks down when we consider the fact that detectives inspected the floor of the elevator shaft before riding down in the elevator, and found in it Mary Phagan’s parasol and a large quantity of trash and debris. Detective R.M. Lassiter stated at the inquest into Mary Phagan’s death, in answer to the question “Is the bottom of the elevator shaft of concrete or wood, or what?” that “I don’t know. It was full of trash and I couldn’t see.” There was so much trash there, the investigator couldn’t even tell what the floor of the shaft was made of! There may well have been enough trash, and arranged in such a way, to have prevented the crushing of the waste material when Frank and Conley used the elevator to transport Mary Phagan’s body to the basement. In digging through this trash, detectives could easily have moved it enough to permit the crushing of the feces the next time the elevator was run down.

33. The defense’s theory of Conley’s guilt involves Conley alone bringing Mary Phagan’s body to the basement down the scuttle hole ladder, not the elevator. But Lassiter was insistent that the dragging marks did not begin at the ladder, stating at the inquest: “No, sir; the dragging signs went past the foot of the ladder. I saw them between the elevator and the ladder.” Why would Conley pointlessly drag the body backwards toward the elevator, when his goal was the furnace? Why were there no signs of his turning around if he had done so? If Mary Phagan’s body could leave dragging marks on the irregular and dirty surface of the basement, why were there no marks of a heavy body being dumped down the scuttle hole as the defense alleged Conley to have done? Why did Mary Phagan’s body not have the multiple bruises it would have to have incurred from being hurled 14 feet down the scuttle hole to the basement floor below?

34. Leo Frank changed the time at which he said Mary Phagan came to collect her pay. He initially said that it was 12:03, then said that it might have been “12:05 to 12:10, maybe 12:07.” But at the inquest he moved his estimates a full five minutes later: “Q: What time did she come in? A: I don’t know exactly; it was 12:10 or 12:15. Q: How do you fix the time that she came in as 12:10 or 12:15? A: Because the other people left at 12 and I judged it to be ten or fifteen minutes later when she came in.” He seems to have no solid basis for his new estimate, so why change it by five minutes, or at all?

35. Pinkerton detective Harry Scott, who was employed by Leo Frank to investigate the murder, testified that he was asked by Frank’s defense team to withhold from the police any evidence his agency might find until after giving it to Frank’s lawyers. Scott refused.

36. Newt Lee, who was proved absolutely innocent, and who never tried to implicate anyone including Leo Frank, says Frank reacted with horror when Lee suggested that Mary Phagan might have been killed during the day, and not at night as was commonly believed early in the investigation. The daytime was exactly when Frank was at the factory, and Lee wasn’t. Here Detective Harry Scott testifies as to part of the conversation that ensued when Leo Frank and Newt Lee were purposely brought together: “Q: What did Lee say? A: Lee says that Frank didn’t want to talk about the murder. Lee says he told Frank he knew the murder was committed in daytime, and Frank hung his head and said ‘Let’s don’t talk about that!'” (Atlanta Georgian, May 8, 1913, “Lee Repeats His Private Conversation With Frank”)

37. When Newt Lee was questioned at the inquest about this arranged conversation, he confirms that Frank didn’t want to continue the conversation when Lee stated that the killing couldn’t possibly have happened during his evening and nighttime watch: “Q: Tell the jury of your conversation with Frank in private. A: I was in the room and he came in. I said, Mr. Frank, it is mighty hard to be sitting here handcuffed. He said he thought I was innocent, and I said I didn’t know anything except finding the body. ‘Yes,’ Mr. Frank said, ‘and you keep that up we will both go to hell!’ I told him that if she had been killed in the basement I would have known it, and he said, ‘Don’t let’s talk about that — let that go!'” (Atlanta Georgian, May 8, 1913, “Lee Repeats His Private Conversation With Frank”)

* * *

The Leo Frank case was a major impetus in the founding of the Jewish ADL and spurred a national mobilization and organization of Jewish power that persists to this day. The combination of money, lies, perjury, bribery, and moral intimidation that was set in the Frank case is still the modus operandi used by our nation’s enemies today. Next article, we’ll continue our exposé of the hoaxes and deceptions used by the Jewish power structure in the Leo Frank case.