Another shocking crescendo occurred within five weeks of the three-month long Mary Phagan murder investigation and pretrial discovery.

After the police were tipped off with what amounted to second, third, and fourth hand reports about the African American Albert McKnight concerning alleged conversations revealed to him by his common-law wife, Magnolia “Minola” McKnight. So the Atlanta police honed in on Minola, arrested her, and received some earth-shattering insights about what was said in the privacy of the Selig household on Saturday, April 26, 1913, and afterward. It would prove to be another major blow for the Leo Frank defense and bring shame upon the Selig family and Jewish community.

Apparently, Minola McKnight had told her common-law husband, Albert McKnight, about dialogue that occurred before in private at the Selig’s place. The conversation occurred between Minola McKnight and her employer’s daughter Lucille Selig Frank, the wife of Leo Frank, and second, McKnight overheard what sounded like concerned discussions between various extended Selig family members and friends about Leo Frank and the murder of Mary Phagan.

Minola’s allegations amounted to the claim that essentially the whole Selig family knew approximately “what really had happened” after-the-fact on that infamous Saturday, April 26, 1913, and they talked about it amongst themselves and around the dinner table while feasting on Minola’s superb down-home Southern African-American style cooking.

The Ultimate Source

It revealed that Frank might have made the murder revelation to his wife Lucille Selig Frank, on the late Saturday evening, April 26, 1913, at about 10:30 p.m. It became the second of Leo’s alleged (hearsay) “murder confessions” inside the official record of the brief of evidence (BOE, July 28 to August 26, 1913). The fourth alleged murder confession (or, in this case, incriminating statement) is located outside the official record, when one considers the Atlanta Constitution, March 9, 1914 (https://www.leofrank.org/library/atlanta-journal-constitution/leo-frank-answers-list-of-questions-bearing-on-points-made-against-him-mar-9-1914.pdf), sustains the third one, and as a result, all four of them would become real.

Four Alleged Murder Confessions Should Determine the Outcome for the Guilt or Innocence Equation of Leo Frank and Provide the Solution to the Mary Phagan Cold Case Murder Mystery

On June 2, detectives requested Minola McKnight come down to the Atlanta police station to determine the veracity of Albert McKnight’s statements he alleged while at work. Albert McKnight would make a number of affidavits concerning these specific events, but they are rarely ever discussed with any depth in the literature concerning the Leo Frank affair, which is a trifle odd considering they resulted in one of the biggest controversies during the investigation into the Mary Phagan murder mystery.

The Albert and Minola McKnight affidavits are in the Leo M. Frank Georgia Supreme Court Case File (1913 to 1915). Albert McKnight would later be caught up in a forged affidavit scandal during the appeals when the Leo Frank defense tricked him into signing something he didn’t agree with (Leo Frank Georgia Supreme Court Records, 1914).

On arrival at police headquarters, Minola was immediately brought into the interrogation room. Unbeknownst to her, she was in for a long round of questioning and given the good old-fashioned “third degree,” also known as the art of “good cop and bad (asshole) cop.” It’s a crude method, but one brutally effective method of information extraction and wearing people down physically, mentally, and spiritually.

The third degree is a tactic perfected over the centuries and generations and still in use today. Outside the United States, waterboarding has been determined to be the most efficient information extraction technique, but there is a controversy over the veracity of tortured evidence. Had they used waterboarding on Leo M. Frank and Jim Conley, perhaps the web of lies would have been ripped away and the truth of the events in the metal room on Confederate Memorial Day would finally be revealed.

Though the Atlanta police were not as sophisticated as they are today, back in the days of the early 20th century, especially in the South, police had greater freedom and were not restricted by the rules, regulations, and bureaucracies within bureaucracies about what they could and could not do behind closed doors during interrogation. It was believed by many, including the police, at the time that African Americans were the easiest of all groups in society to “break” in the interrogation room. This belief was reinforced by the reality that Black men and women at that time had a great deal to fear from a White-dominated justice system which didn’t always treat them fairly. Despite all this, Jim Conley stood up through three weeks of intense grilling by the police.

Though it was early on, Minola McKnight was a tough nut to crack, but the house always wins (usually). At the time of her arrest, she exploded into hysterics, shouting out flamboyantly about her own innocence regarding the murder of Mary Phagan, but she was never a murder suspect.

When police couldn’t “break her” right away, they had another technique within the “plethora of tools” within their historical arsenal. The technique of caged discomfort usually works wonders at getting people to “sing,” so at the behest of investigators and the Solicitor General, they detained Minola on “suspicion,” locking her up in solitary confinement against the righteous tenets of our Constitutional habeas corpus rights.

Marinate the Black Magnolia

The marinating of Magnolia “Minola” McKnight overnight in the dungeon-like “cooler” of solitary confinement, thus making the poor woman sleep overnight in jail, worked wonders, and when the morning sun peaked just above the horizon, she was ready to sing like a bird, sing it loud, like at a charismatic Baptist church, telling all the morbid details of direct conversations and hearsay that secretly occurred in the Selig home at 68 East Georgia Ave., Atlanta, GA.

The police stenographer, Mr. February, and Minola McKnight’s lawyer, Mr. Gordon, were fully present and conscious to witness her signature, but Mr. Gordon had to wait just outside the room while she was being interrogated. There have been long held claims that the testimony was coerced from Minola McKnight, but what stood out of the affidavit were several sustaining factors.

1. Leo Frank was drunk on the evening of the murder.

2. Leo Frank confessed the murder to his wife.

3. Whom was Leo Frank saving his kisses for?

4. Why did Leo Frank so thoughtfully buy his wife a box of chocolates at Jacob’s Pharmacy at 6:30 p.m.?

5. Leo Frank was suicidal on the night of the murder, asking for his pistol to kill himself.

6. Leo Frank may have shown remorse to his wife about the murder.

June 3, 1913: When Another Breakthrough in the Mary Phagan Murder Investigation Unraveled

Magnolia McKnight was the high-yellow African-American personal cook and light household cleaner at the rented Selig residence of Leo Max Frank, Lucille Selig Frank, Emil Selig, and Josephine Cohen Selig.

While police were taking Minola’s deposition, she verbalized and signed an irrevocably damaging statement on June 3, 1913, one she would later deny.

The McKnight affair would amount to revealing the second known Leo Frank alleged (hearsay) murder confession out of the three from the surviving legal documents of the Brief of Evidence, 1913 (BOE, 1913), but what about the fourth?

The fourth would sustain Minola McKnight’s affidavit.

The Four Leo Frank Alleged Murder Confessions and Incriminating Statements: Two Private on April 26, 1913, and One Public at the Trial on August 18, 1913, and One in the Newspaper March 9, 1914

1.Leo Frank alleged (hearsay) murder confession number one was made privately to James Conley at the National Pencil Company on the afternoon of April 26, 1913 (Affidavits of James “Jim” Conley, May 1913 and Jim Conley, trial testimony, Fulton County Superior Court, August 1913).

2. Leo Frank made his second alleged (hearsay) murder confession in private to Lucille Selig Frank in the second-floor bedroom of the Selig home on the evening of Confederate Memorial Day, Saturday April 26, 1913 (Minola McKnight, June 3, 1913, States Exhibit J). This confession was corroborated by Lucille’s 1954 cremation request and hence the reason why when she passed away April 23, 1957, the unoccupied grave plot #1 reserved for Lucy S. Frank remained empty in the Mount Carmel Cemetery. Mount Carmel Cemetery, plot #1 is immediately adjacent to Leo Frank’s (April 17, 1884, to August 17, 1915) occupied grave plot #2 as of his burial date August 20, 1913).

3. The most shocking Leo Frank incriminating statement was his third one, made publicly at the Leo Frank trial in the Fulton County Superior Court after he mounted the witness chair on August 18, 1913. Leo Frank told the jury he had unconsciously gone to the only bathroom existing on the second floor, within the metal room in the rear of that floor. This shocking revelation by Leo Frank was to account for the time Monteen Stover had indisputably said his office was empty between the entire time of 12:05 p.m. and 12:10 p.m. on April 26, 1913. The defense disputed Monteen Stover’s testimony, and thus Leo Frank’s Monday, April 28, 1913, State’s Exhibit B became inescapably incriminating when juxtaposed against his Monday, August 18, 1913, trial statement to counter Stover. Leo Frank made the most incriminating statements during the Phagan murder investigation and at his own trial.

Tuesday, June 3, 1913: State’s Exhibit J, an Earth-Shattering Bombshell

There were several major revelations incriminating Leo Frank during the murder investigation of Mary Phagan, but of them all State’s Exhibit J was mind-blowing. The bombshells were not directly from Leo Frank per say, but from other eyewitnesses close to him, and these second, third, and fourth hand reports should not to be confused with Frank’s numerous foot-in-mouth blunders he made during the course of the Mary Phagan murder investigation and trial.

For this purpose, we have separated bombshells and blunders, despite the fact they are virtually equal.

The Bombshells

Monteen Stover came back to the pencil factory with her stepmother to get her paycheck after a failed attempt on April 26, 1913.

1. The first major bombshell was the revelation of Monteen Stover: she had failed in her attempt to get her pay envelope in Leo Frank’s second-floor business office, waiting from 12:05 p.m. through 12:10 p.m. on Confederate Memorial Day, Saturday, April 26, 1913.

Armed with this knowledge from Monteen Stover, police officer Black and Pinkerton Detective Harry Scott approached the cell of Leo Frank and asked him if he had been in his office every minute from noon to 12:35, and Frank said yes. Then and there, the statement of Monteen Stover had become a nuclear bombshell, because Leo Frank had just blundered by opening his mouth (he should have requested his lawyer present first). Frank had just created a point of contention and contradiction that was potentially inescapable. It also meant that Leo Frank possibly had lied about his own whereabouts and that of Mary Phagan that infamous afternoon between 12:05 and 12:10 p.m. Was there a sign of cooperation? And if so what went wrong? Was Mary Phagan coaxed back there or did they have prearranged meeting? Travel down all the possible permutations of the time web.

2. The second major bombshell dropped was when Jim Conley, after three affidavits, decided to cut all the pretenses and most of the bullshit and finally spill the beans about approximately what happened on that afternoon. Three days of thunderous cross-examination from two of the best lawyers money could buy in Georgia, Luther Zeigler Rosser and Reuben Rose Arnold, failed to shake or break the account of Jim Conley.

Not exactly — Jim Conley got the hiding in the wardrobe testimony crossed up, when it was an hour earlier. What was Jim Conley trying to block out that might have occurred during the real time segment between noon and 1:00 p.m.? One can only shudder at what Jim Conley fell asleep to after he heard Mary Phagan’s scream and Monteen Stover leave. Was there connivance?

3. The third major bombshell was Minola McKnight’s account of what was said in the Frank-Selig household…

The Dirty Devil Is in the Delicious Details

State’s Exhibit J was captured by a sworn and official stenographer in the police station house and witnessed by detectives, Hugh Dorsey, and Magnolia “Minola” McKnight’s lawyer named Mr. Gordon. It was a bombshell for the defense, and Steve Oney would make the vivid suggestion that in a Godzilla-like fashion Minola ripped the roof from the Selig-Frank household and provided a secondhand fill in the gaps, approximate loose snap shot of what went on behind closed doors after the twilight hours of Confederate Memorial Day, Saturday, April 26, 1913, and the days that followed thereafter – without the juiciest details.

There in the Leo-Frank-Lucille-Selig marital bedchamber unmistakable and harrowing intimations were made sometime between the time Frank arrived at home at just before 6:30 p.m. until his “bedtime” at 10:30 p.m. There in the privacy of their bedroom, Leo Frank revealed he was not a total sociopath, because through his words and demeanor, he expressed remorse and guilt over something he wished he had not done, but was now in a “world of shit” to borrow the words of private “Gomer Pyle” from the movie Full Metal Jacket (1987).

A Little Red Flag

After failing to reach Frank, the police, in reflection upon that event, would raise a little red flag against Leo Frank because everyone else they tried to reach on the phone answered. Another interesting point is the phone at the Selig residence was in the dining room downstairs. While Leo could barely sleep upstairs in his second-floor bedroom over the dining room with his wife sleeping on the rug, snuggling in fetal position with a quilt, they both surely could hear the phone ring, especially Lucille, whose head rested almost next to the floor. Even with her head on a pillow, she likely could have heard it ringing if it were not put off the hook.

Lucille was the first to wake up on the morning of April 27, 1913, and when the doorbell rang at the Frank-Selig home, she answered. Though Leo Frank had finally answered the phone before the police arrived, when he came downstairs half-naked and put on his dress shirt, he fumbled and butterfingered with his collar and tie, and began asking rapid-fire questions before the police could even get a chance to answer. And then Leo Frank denied knowing Mary Phagan from that day forward.

Magnolia Released from the Police, Tuesday, June 3, 1913

Within twenty-four hours of making her irreversibly damaging testimony, Minola McKnight would throw that incensed attitude in that uniquely colorful African-American style, with her lips puckered, the left hand made into a prone fist buried deep in her hip; her right hand’s fingers were popping and snapping in giant Z patterns, all whilst her head began sliding horizontally side to side across the lateral width of her shoulders, without her head ever changing its plumb angle. You could balance a glass of water on the top of her head without it tipping over, despite it sliding side to side.

I Aen’t No Snitch, Niga Step Off!

After being released from the police station, Magnolia changed her tune faster than Leo Frank could wink his left eye. She began back peddling at a furious pace and attempted afterward to recant the affidavit she just made. As a free woman again, Minola knew she was in a grave situation after betraying the family that loved her as one of their own. She began, in the presence of a newspaper reporter, within barely a day of her release, saying that the statement wasn’t true. It was a little too late, and no one was buying her denials. Nine days after that whole debacle, an “unknown” knife-wielding assailant would slash Minola’s face wide open. Though the shanker was never caught, Minola knew the score and couldn’t do a damn thing or even peep a word about it.

In terms of Black-Jewish relations, Minola would learn a powerful lesson as a black woman, working for a prominent white Jewish household of wealth and privilege. Very simply put, you don’t betray your loyalty by opening your mouth in a harmful way about private family matters, especially against the well-connected, successful, and respected Selig-Frank clan, a family amongst the highest echelons of Atlanta’s Jewish aristocracy, philanthropy, and society.

Life was really cheap in 1913 Atlanta, and Minola was lucky she got off easy with her face cut up and that she didn’t disappear into the bottom of a boggy swamp with the catfish at the far outskirts of greater Atlanta. Back in those days they wouldn’t have wasted a single drop of sweat from a bloodhound dogs brow looking for a lost black woman, especially a cook a decade and thirty pounds away from becoming the stereotypical uniform-clad black mammy busy body engaging in jibber jabber and gup. In fact, if Minola had gone missing, no one would have batted an eyelash for her because the value of a “Negress,” as they called African-American women at the time, was a dime a dozen. Nonetheless, despite her perceived value in a White Separatist South, the police and prosecution gave her full credibility to the letter of her affidavit, because something about her words rang true, and her husband Albert McKnight was willing to corroborate the statements.

Unbeknownst to Magnolia at the time, police and detectives would feel she was telling the truth, because Minola’s statement tended to corroborate some of the peripheral facts and observations connected with the two police officers who went to Leo Frank’s house on the morning of Sunday, April 27, 1913. One of them being, Leo Frank was drunk.

April 27, 1913, 7:00 a.m.

On April 27, 1913, when Atlanta police arrived at the Selig-Frank household at 68 East Georgia Avenue, they noticed Leo Frank looked like he was badly hungover and made some sarcastic, condescending comments to Leo’s wife, Mrs. Lucille Selig Frank, asking her if she had any whiskey for them. Lucy Frank was sharp enough on her feet to understand the substance of the suggestion, so she responded by deflecting the truthful insinuation against her husband. Lucille played it off by saying that her father Papa Emil Selig drank it all, but in truth, Leo Max Frank had guzzled the liquor closet down until it was bone dry the night before. He also chain-smoked his throat hoarse.

The police recalled that on Sunday morning, April 27, 1913, Leo Frank was ghostly Pale, shaking, fumbling with his collar, asking questions much faster than they could answer, and his voice was very hoarse. There was something weird about him that morning, and the richness of the details about what went on secretly in the household according to Minola McKnight’s damaging statement took on a life of its own, creating added circumstantial evidence against Leo Frank. And to compound the controversy further, Minola later denied her deposition.

Meet Albert McKnight

From the Jewish perspective, the original instigator of this irreparable episode of betrayal was Magnolia’s husband Albert McKnight, who should have kept his mouth shut about what his gossipy wife told him. He would later get a righteous Southern ass whooping, an unfortunate byproduct of informing on the prominent Selig-Frank household to the police. The beating Albert received was collateral damage in a Jewish-Black conflict and a result of a family-employee affair involving his wife.

Your Services Are No Longer Needed, Magnolia

Minola’s daily cooking, light cleaning, and in-house laundry services would no longer be required as the end of the summer of 1913 rolled around. At the time of her dismissal, she had served her usefulness at the trial, repudiating her sworn statement to the police, but the debacle she created could not be undone.

Just Before the Fast-Approaching Leo Frank Trial, Which Was Just Around the Corner–Stomachs Were in Knots

Before the murder trial, Minola McKnight would have been “dressed down”; she was most certainly spoken with and knew the score after her slashing by an unknown assailant. She would hold fast for the Selig-Frank family, testifying for the defense during the trial, denying the affidavit she had made to the police in the presence of her lawyer Mr. Gordon. However, no one was really buying her repudiation because it fit too well with the rest of the circumstantial evidence. There were too many other extenuating circumstances, like the heavy drinking that tended to link Leo Frank to the crime and corroborate Minola’s “State’s Exhibit J.” Sometimes in life, there are things you simply cannot undo or unsay, no matter how much indignant barking, back peddling, and denying you do.

Words You Can’t Eat

When all things were considered, because the affidavit of Minola McKnight (State’s Exhibit J) amounted to an alleged (hearsay) Leo Frank murder confession and an acknowledgment of his guilt by the Selig family, it created strong circumstances against Frank. Two more Leo Frank alleged murder confessions and incriminating statements would surface at the trial: one revealed to the jury by Jim Conley on August 4, 1913, under examination and the other, a most shocking incriminating statement given by Leo Frank himself on August 18, 1913. With careful consideration, looking back, it was impossible for most neutral observers to take the repudiation of Minola’s State’s Exhibit J seriously.

Insincerity

Another reason no one really believed Minola’s recanting at the trial was because the recanting came off as weak, contrived, loping, and half-insincere–her stated reason for giving the statement came off more like regrets than it was “tortured” out of her:

MINOLA McKNIGHT (c[olored]), sworn for the Defendant.

I work for Mrs. Selig. I cook for her. Mr. and Mrs. Frank live with Mr. and Mrs. Selig. His wife is Mrs. Selig’s daughter. I cooked breakfast for the family on April 26th. Mr. Frank finished breakfast a little after seven o’clock. Mr. Frank came to dinner about 20 minutes after one that day. That was not the dinner hour, but Mrs. Frank and Mrs. Selig were going off on the two o’clock car. They were already eating when Mr. Frank came in. My husband, Albert McKnight, wasn’t in the kitchen that day between one and two o’clock at all. Standing in the kitchen door you can not see the mirror in the dining room. If you move up to the north end of the kitchen where you can see the mirror, you can’t see the dining room table. My husband wasn’t there all that day.

Mr. Frank left that day sometime after two o’clock. I next saw him at half past six at supper. I left about eight o’clock. Mr. Frank was still at home when I left. He took supper with the rest of the family. After this happened the detectives came out and arrested me and took me to Mr. Dorsey’s office, where Mr. Dorsey, my husband and another man were there. I was working at the Selig’s when they come and got me. They tried to get me to say that Mr. Frank would not allow his wife to sleep that night and that he told her to get up and get his gun and let him kill himself, and that he made her get out of bed. They had my husband there to bulldoze me, claiming that I had told him that. I had never told him anything of the kind. I told them right there in Mr. Dorsey’s office that it was a lie. Then they carried me down to the station house in the patrol wagon. They came to me for another statement about half past eleven or twelve o’clock that night and made me sign something before they turned me loose, but it wasn’t true. I signed it to get out of jail, because they said they would not let me out. It was all written out for me before they made me sign it.

CROSS EXAMINATION.

I signed that statement (State’s Exhibit ” J “), but I didn’t tell you some of the things you got in there. I didn’t say he left home about three o’clock. I said somewhere about two. I did not say he was not there at one o’clock. Mr. Graves and Mr. Pickett, of Beck & Gregg Hardware Co., came down to see me. A detective took me to your (Mr. Dorsey’s) office. My husband was there and told me that I had told him certain things. Yes, I denied it. Yes, I wept and cried and stuck to it. When they first brought me out of jail, they said they did not want anything else but the truth, then they said I had to tell a lot of lies and I told them I would not do it. That man sitting right there (pointing to Mr. Campbell) and a whole lot of men wanted me to tell lies. They wanted me to witness to what my husband was saying. My husband tried to get me to tell lies. They made me sign that statement, but it was a lie. If Mr. Frank didn’t eat any dinner that day I ain’t sitting in this chair. Mrs. Selig never gave me no money. The statement that I signed is not the truth. They told me if I didn’t sign it they were going to keep me locked up. That man there (indicating) and that man made me sign it. Mr. Graves and Mr. Pickett made me sign it. They did not give me any more money after this thing happened. One week I was paid two weeks’ wages.

RE-DIRECT EXAMINATION.

None of the things in that statement is true. It’s all a lie. My wages never have been raised since this thing happened. They did not tell me to keep quiet. They always told me to tell the truth and it couldn’t hurt (Brief of Evidence).

Minola had her unwanted fifteen minutes of fame, and she would disappear from the limelight into the silent gray of history, behind the stage curtain of the “Leo Frank Greek tragedy.” And she would not make another debut, neither to be seen or heard of again in the three major local newspapers, but her life with husband Albert McKnight went on just the same…

Chocolate Surprise

Rarely ever discussed or adequately answered is who was the girl Leo Frank was saving his kisses for?

Perhaps Mary Phagan some contend, or had Leo Frank planned on a little light whoring in the later afternoon of the Sabbath? And the thoughtful box of chocolates Leo Frank offered Lucy Selig Frank to assuage his guilt was not missed. Some have suggested that if indeed Leo was saving his kisses for Mary Phagan, perhaps there was more than meets the eye to this case. Was there signs of cooperation? Why was she alone in a shuttered factory with Leo Frank in the metal room at the back of the second floor? What caused Leo Frank’s right fist to drop like a bucket of bricks on Mary Phagan’s left eye? Was Phagan the paragon of Southern womanhood defending her honor, or was a meeting intended for the metal room at noon? The narrowness of the timeline suggests there certainly could have been other intrigues and permutations at play in the background of this case.

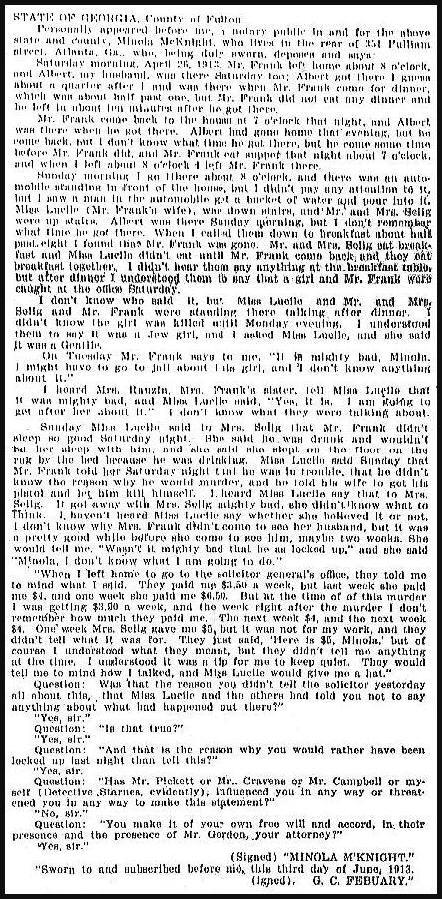

STATE OF GEORGIA, County of Fulton

Personally appeared before me, a notary public. In and for the above state and county. Minola McKnight who lives in the rear of 354 Pulliam Street, Atlanta Georgia, who being duly sworn deposes and says:

Saturday morning, April 26, 1913, Mr. Frank left home about 8:00 o’clock, and Albert, my husband was there too. Albert got there, I guess, about a quarter after 1:00 and was there when Mr. Frank come for dinner, which was about half past one, but Mr. Frank did not eat any dinner and he left in about ten minutes after he got there.

Mr. Frank come back to the house about 7:00 that night, and Albert was there when he got there. Albert had gone home that evening but he come back, but I don’t know what time he got there. But he got home some time before Mr. Frank did, and Mr. Frank eat supper about 7 o’clock, and when I left about 8 o’clock I left Mr. Frank there.

Sunday morning I got there about 8 o’clock and there was an automobile standing in front of the house, but I didn’t pay any attention to it. But I saw a man get a bucket of water and pour into it. Miss Lucille (Mr. Frank’s wife) was downstairs, and Mr. and Mrs. Selig were upstairs. Albert was there Sunday morning but I don’t remember what time he got there. When I called them down to breakfast at half past eight I found Mr. Frank was gone. Mr. and Mrs. Selig ate breakfast and Mrs. Lucille didn’t eat until Mr. Frank come back, and they ate breakfast together. I didn’t hear them say anything at the breakfast table, but after dinner I understood them to say that a girl and Mr. Frank were caught at the office Saturday.

I don’t know who said it, but Miss Lucille and Mr. and Mrs. Selig and Mr. Frank were standing there talking after dinner. I didn’t know the girl until Monday evening. I understand them to say it was a Jew girl, and I asked Miss Lucille, and she said it was a gentile.

On Tuesday Mr. Frank says to me “It looks mighty bad Mineola, I might have to go to jail about this girl, and I don’t know anything about it.”

I heard Mrs. Rauzin, Mrs. Frank’s sister, tell Miss Lucille it was mighty bad and Miss Lucille said, Yes, it is, I am going to get after her about it.” I don’t know what they were talking about.

Sunday, Miss Lucille said to Mrs. Selig that Mr. Frank didn’t sleep so good Saturday night. She said he was so drunk and wouldn’t let her sleep with him, and she slept on the floor, on the rug, by the bed, because he was drinking. Miss Lucille said Sunday that Mr. Frank told her Saturday night he was in trouble. That he didn’t know the reason why he would murder, and he told his wife to get his pistol, and let him kill himself. I heard Miss Lucille say that to Mrs. Selig. It got away with Mrs. Selig mighty bad, she didn’t know what to think.

I haven’t heard Miss Lucille say whether she believed it or not. I don’t know why Mrs. Frank didn’t come to see her husband, but it was a pretty good while before she comes to see him, maybe two weeks. She would tell me, ” Wasn’t it mighty bad that he got locked up” and she said “Minoela, I don’t know what I am going to do.”

When I left home to go to the solicitor general’s office, they told me to mind what I said. They paid me $3.50 a week, but last week she paid me $4.00, and one week she paid me $6.50. But at the time of this murder I was getting $3.50 a week and the week after the murder I don’t know how much they paid me. The next week $4.00 and the next week $4.00. One week Mrs. Selig gave me $5.00, but it was not for my work, and they didn’t tell me what it was for. They said ‘Here is $5 Minola’, but of course I understood what they meant, but they didn’t tell me anything at the time. I understood it was a tip for me to keep quiet. They would tell me to mind how I talked and Miss Lucille would give me a hat.

QUESTION: “Was that the reason you didn’t tell the solicitor general yesterday all about this, that Miss Lucille and the others had told you not to say anything about what happened out there?”

“Yes, Sir.”

QUESTION: “And that is the reason why you would have rather been locked up last night than tell this?”

“Yes, Sir.”

QUESTION: Has Mr. Pickett, or Mr. Cravens, or Mr. Campbell or myself [Detective Starnes evidently], influenced you in any way, or threatened you in any way to make this statement?”

“No, Sir.”

QUESTION: “You make it of your own free will and accord, in their presence and the presence of Mr. Gordon, your attorney?”

“Yes, Sir.”

(Signed) “Minola McKnight”

Sworn to and subscribed before me, this third day of June, 1913.

(Signed ) G.C. Febuary

—————————————————————-

Source:

Available for review and download, please visit: Leo M. Frank, Plaintiff in Error, vs. State of Georgia, Defendant in Error. In Error from Fulton Superior Court at the July Term 1913. Brief of Evidence 1913. (Located within the 1,800 page Georgia Supreme Court Case File, Volume 1 and 2).

Minola McKnight Affidavit, Part 1: https://www.leofrank.org/georgia-archive/B057/D260-B057-0063.JPG right mouse click and save as).

Minola McKnight Affidavit, Part 2: https://www.leofrank.org/georgia-archive/B057/D260-B057-0064.JPG (right mouse click and save as).

Minola McKnight Affidavit, Part 3: https://www.leofrank.org/georgia-archive/B057/D260-B057-0065.JPG (right mouse click and save as).

Minola McKnight Affidavit, Part 4: https://www.leofrank.org/georgia-archive/B057/D260-B057-0066.JPG (right mouse click and save as).

See: Internet Archive copy of Leo M. Frank, Plaintiff in Error, vs. State of Georgia, Defendant in Error. In Error from Fulton Superior Court at the July Term 1913. Brief of Evidence 1913. Text copy available here on this library archive.

Leo Frank Alleged (Hearsay) Murder Confession #1 made to Jim Conley: The alleged Leo Frank NPCo murder confession, https://www.leofrank.org/jim-conley-august-4-5-6/.

Leo Frank Alleged (Hearsay) Murder Confession #2 made to Lucille Selig Frank: The alleged Leo Frank bedroom murder confession, Minola McKnight and Lucille Selig Frank, https://www.leofrank.org/states-exhibit-j/.

Leo Frank Incriminating Statement #3 made to the Judge and Jury: The Leo Frank murder trial incriminating statement, https://www.leofrank.org/confession.

Leo Frank Incriminating Statement #4 made to the whole world through the newspaper: The Leo Frank jailhouse incriminating statement, Leo Frank Answers List of Questions Bearing on Points Made Against Him, Atlanta Constitution, March 9th, 1914.

Albert McKnight Affidavit that Sparked the Minola McKnight Affair:

word count 5, 025

One thought on “Magnolia “Minola” McKnight, State’s Exhibit J, June 3, 1913, Leo Frank Admission Amounting to Alleged (Hearsay) Murder Confession Number 2”

Comments are closed.

[…] Minola McKnight […]