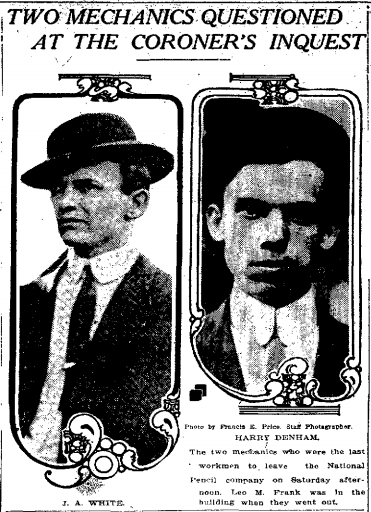

![J. A. White [left and] Harry Denham. The two mechanics who were the last workmen to leave the National Pencil company on Saturday afternoon. Leo M. Frank was in the building when they went out. Photo by Francis B. Price, Staff Photographer.](https://www.leofrank.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Newt-Lee-Tells-His-Story-During-the-Morning-Session-300x414.png)

Atlanta Constitution

Thursday May 1st, 1913

Was the man who first assaulted and then brutally killed Mary Phagan last Saturday night hiding in the basement of the National Pencil company when the watchman, Newt Lee, came down and discovered the girl’s mutilated body early Sunday morning?

This is the question that rose to everyone’s mind, following the testimony of the negronight watchman, at the coroner’s inquest Wednesday. In direct contradiction to the evidence of every policeman who had been on the scene, the negro declared that he found the body, lying face up, with the head toward the wall. When the police arrived, the body was lying face down, with the head pointing toward the front of the building.

The most severe cross examination could not shake the negro. He stuck to his story, never seeming to waver for an instant. So convincing was his air that it became the general idea that the murderer must have been in the cellar at the time, waiting to burn the body of his victim. Lee’s coming down into the cellar may have frightened him away.

He declared that when he reported for work at 4 o’clock on the afternoon before the tragedy, his employer told him to go home until 6 o’clock. Frank looked nervous and excited at the time, he said. He also said that Frank had called him up later in the night, to find if everything was all right, something that he had never done before.

What was thought earlier in the day to be damaging to the negro—his declaration that he was positive that it was the body of a white girl as soon as he saw it—was brushed aside when he explained that he saw the difference because of the hair, which was straight and brown; totally unlike that of a negress.

The same jury that was used by Coroner Donehoo Monday morning was reimpaneled at 9 o’clock Wednesday morning, when the inquest reconvened.

Inquest at Police Headquarters.

The inquest was held at police headquarters. W. F. Anderson, a call officer on the police force, who took the negro’s message, when he reported the finding of the body, was the first to testify.

He described the body as he found it after the negro had led him and other officers to it. He stated specifically that the head pointed toward the front of the building and that the body was lying face down.

Minutely, he gave all of the grewsome details of the dead girl’s appearance. He told how evident it had been that she had been in a struggle to the death, how her stocking was torn, her shoe missing and her whole face discolored by bruises and grime. So shocking was her state, he declared, that he did not know at first whether she was white or colored.

He said that her neck was knotted around with twine and a piece of cloth, evidently torn from her underskirt.

He declared that the staple that had been used to hold the door from the basement closed had been drawn.

Physician Does Questioning.

Dr. J. W. Hurt took up the questioning at this point.

“Could the negro have seen a body lying 20 or 30 feet away from where he was standing, by the light of the lantern that he carried?” he asked.

“He could not,” replied the policeman. “At the most he could have seen for 12 or 15 feet. His lantern was very old and dirty.”

Sergeant R. J. Brown, who also went to the scene of the crime, was next called before the jury. He corroborated the other policeman’s testimony, in regard to the impossibility for anyone to distinguish the race of the girl without the most minute examination. He also declared that the negro could have seen nothing, standing 25 feet away from the body. “It was very hard to see with our regular police flash lights,” he said, “ and the negro only had a very weak lamp. I am sure that he could not have seen anything at a distance of 25 feet.”

“This is nothing but a child,” he testified that he exclaimed when he first saw the body. He said that he could not tell her color until he rolled down one stocking and looked at the knee.

He went over the revolting details of the girl’s condition. His testimony did not conflict with his brother officers’ in any way, but he told of some matters which the other had failed to bring out.

He said that there was dirt in her mouth even. The negro nightwatchman had told him, he said, that he rarely came down in the cellar, but that he had a special reason for doing so on that night.

When he was questioned about the telephoning of the news to Superintendent Frank that the sergeant’s information became most damaging.

“We called up at once almost,” he testified, “but, although we told central that a girl had been murdered and that it was of the utmost importance that we get the number, we could not get in communication with Mr. Frank until much later in the day.”

Blood-Stained Garments Shown.

It was then that the most dramatic occurrence of the whole day took place. A one-piece purple silk dress, dirty and torn and blood-stained, and a gunmetal slipper, worn by Mary Phagan on the night of the murder, were shown to the jury.

Ben Phagan, the dead girl’s sailor brother, rose from his seat and looked down on the little heap of clothes with eyes that tragically stared. For a moment he stood so, and then walked out, his head bowed, his hands over his eyes.

Upon being recalled, Officer Anderson testified that the body of the girl had still been warm when he came there and that blood was flowing from some of the wounds.

Police Sergeant L. S. Dobbs, who was next called, identified the notes that had been found by the girl’s body. He declared that, after a minute examination, he had been able to say with authority that the body was that of a white girl. External appearances, he said, tended to show that the body had been dragged and thrown into the corner.

He said that after examining the body he turned to the negro watchman and accused him of having either committed the crime or of knowing something of it. The negro, he said, denied all knowledge of the affair.

Read Note to Negro.

He said that he then read him the note in which the girl is purported to have written: “Tall, black, thin negro did this. He will try to lay it on night—“ The negro then replied, he declared, “That means me—the night watchman.”

Other evidence simply corroborated the testimony of his brother officers.

Newt Lee, the negro night watchman, was called on the stand at 11:45 o’ clock. He testified that Frank had especially instructed him to come to work two hours earlier than usual that Saturday, because of its being a holiday.

“Go out and have some more fun,” Frank told him when he came to work at 4 o’ clock, he declared. He explained that he made a round of the building every half-hour, only going to the basement when he had an unusual amount of time on his hands.

He said that Frank was still in the building when Gantt, a former bookkeeper, came to the door and asked to be allowed in to get an old pair of shoes that he had left inside. The negro declared that he had told Gantt that it was against the rules, but that he would ask his employer.

Frank Looked Frightened.

Lee declared that Frank looked frightened when he told him that Gantt was downstairs. He thought that this might have been caused by Frank’s fear that the other, whom he had recently quarreled with and discharged, might “do him dirt.”

He said that Gantt got the shoes, wrapped them up and made an engagement with someone over the telephone for 9 o’clock that night. The negro was unable to say who Gantt had talked to, but he said that it was a lady.

“How did you know?” he was asked. “By the name,” he replied. He could not remember the name when further questioned, however.

He said that he saw Gantt leave, passing on down the street. He said that he did not know when Frank left, however. He explained the superintendent might have come back at any time, anyway, as he had a key.

He said that he went down into the basement at about 7 o’clock, after making a round of the building. He declared that the gas jet, which he had left burning when he left before, that morning, was not burning as brightly as before.

Frank Calls Up.

He said that shortly after this Frank called up to find if everything was all right. “It is as far as I know,” he declared he answered.

He said Frank called before at night

When he declared that he had found the body lying with the face up, the coroner directly asked him, “Why did you turn it over?”

“I didn’t,” stoutly averred the negro.

He declared that he had punched the time clock every half-hour; that he himself had put in a fresh slip with Frank.

He said that when he first saw the body in the basement it had looked very vague in its outline, and that he thought that boys had put it there to frighten him. It was only when he saw the bloody face and straight hair, he said, that he recognized it as the body of a white woman. He then became frightened and called up the police.

He said that he had been told by employers on Sunday following his arrest that he had punched the clock regularly Saturday night.

He emphatically declared that his lantern had been cleaned Friday and that it was in good condition. He said that a negro fireman (Knollys) probably had a key to the back door of the building, kept open during the day.

Thinks He Saw Girl.

J. G. Spier, of Cartersville, testified that Saturday afternoon at about 4 o’clock he passed the factory and saw in front of it a 17-year-old girl and a man about 25 years old, both very much excited. He said that he came back nearly an hour later and noticed the same couple standing at the same place.

He said that he visited the body at Bloomfield’s undertaking establishment and was sure that the dead girl was the same one that he saw Saturday afternoon. He said that Frank had the same “outline” as the man he saw, but would not identify him positively. Mr. Spier’s testimony brought the morning session to a close.

Friends of L. M. Frank, superintendent of the National Pencil company, gave out yesterday for the first time their theory of how Mary Phagan came to her tragic death. They visited the scene of the crime, and, claiming that Frank has been unjustly held and questioned by the police, they are pointing out how the girl could have been robbed, assaulted and murdered without anyone connected with the factory knowing anything about it.

They point to the foot of the stairway by which the girl would have left the factory and show how easily a man could have hidden behind the railing, which is closely boarded up.

“The foul criminal,” they state, “knew it was pay-day, and as it was Memorial day, the place would close early in the afternoon. He could have hidden at the foot of the stairway and when the girl came down the steps with her money in her purse, seized her and thrown her into the hole which leads to the basement to the left of the elevator shaft. It could all have been done so swiftly by a strong-armed man that the girl would have had no time to make an outcry before she was insensible in the basement.

“Then the criminal could have quickly followed on the ladder that stood in the hole and led from the first floor to the basement. Down in the basement he had ample opportunity to carry out his hellish purposes. His exit was easy, as has been shown in the newspapers. No one could have heard or seen the crime committed who was passing in the street or who was on the second or third floors.”

“We are not advancing theories in the defense of Mr. Frank,” states S. S. Selig, who was among those who made an inspection of the factory Wednesday, “for he needs no defense. But the theory we advance is so plausible and fits so well into the clues that have been found that it is remarkable the officers have not worked along that line. The girl’s parasol was found at the foot of the ladder, where it could have fallen when she was thrown into the hole. That the purse and money were missing shows that there was robbery as well as assault and murder.”

* * *

Atlanta Constitution, May 1st 1913, “Newt Lee Tells His Story During Morning Session,” Leo Frank case newspaper article series (Original PDF)