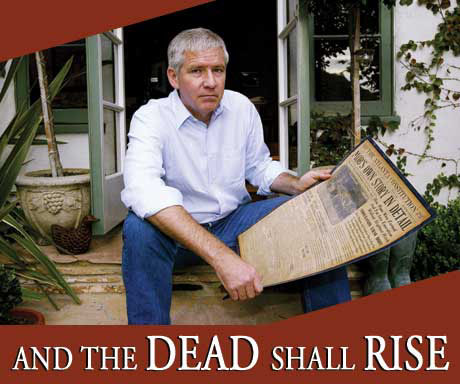

Steve Oney, Holding an Atlanta Constitution Newspaper, August 18, 1915 Issue

And The Dead Shall Rise: The Murder of Mary Phagan and the Lynching of Leo Frank (742 pages) by Steve Oney, published in 2003, through Pantheon Books in New York. The book is available from ebay.com, and www.Amazon.com (including many other popular online stores).

Background Information on Steve Oney

Steve Oney is a journalist-author who was born in metro Atlanta, Georgia, in 1954, and currently resides in the Hollywood Hills section of Los Angeles, California. Oney was raised and educated in Georgia during his most formative years. He graduated from Peachtree High School (Varsity football, basketball, and baseball) in Dunwoody, GA (1972). According to Dr. Sherrie Whaley (2004), “Oney was educated at the University of Georgia, Grady College [and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in Journalism, with a minor in English], 1979, and a Harvard Nieman Fellow, 1982. After brief tours as a reporter for The Greenville (S.C.) News and The Anderson (S.C.) Independent, he worked for many years as a staff writer for Atlanta Weekly, the Sunday magazine of The Atlanta Journal & Atlanta Constitution.” Not exclusive to the East Coast, his wide range of journalistic experience on the ground stretches to California where he moved in the 1980s, “Steve Oney was a senior editor at Los Angeles magazine (Forward, May Issue, 2009). Oney has contributed to “Playboy, GQ, Premiere, Esquire, New York Times” (Welcome Steve Oney, Journalism Department Professional in Residence, Nov. 1 through 5, October, 2004).

Steve Oney is happily married to a Jewish woman (Jewish Journal, February 5, 2004) named Madeline Stuart, an interior decorator and fashion designer. Together the creative couple raise their beloved dog named Beatrice, a professional Jack Russell terrier.

For the Masses of Readers Interested in the Leo Frank Case (1913 to 1986)

Steve Oney couldn’t have put it better when he described the Leo Frank case as one of the most incendiary and complex episodes of Georgia’s past (Georgia Magazine, Features, Vol. 83, No. 4, March 2004). Indeed, no one at the time had anticipated that after Leo Frank’s trial, the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith would form on his behalf one month later or that his two years of appeals to State and Federal courts were destined to evolve into a national cause celebre that would enrage the people of Georgia and the South to lynch him.

When Leo Frank had exhausted all of his appeals in the State and Federal Court System during the affair, he was left with one last chance to prevent his scheduled execution on June 22, 1915. A gubernatorial commutation of his death sentence to life in prison was seen as his last hope to continue fighting for vindication. A stay of execution would have given Leo Frank the opportunity for renewed pursuit of exoneration and freedom. Leo Frank first petitioned the Prison Commission of Georgia for a recommendation of clemency as formality, because it was prerequisite to petitioning the governor for executive clemency. The Prison Commission denied the petition of Leo Frank by a vote of 2 to 1.

On June 21, 1915, one day before Leo Frank was scheduled to hang, the outgoing Governor of Georgia, John M. Slaton, used his constitutional powers to reduce Leo Frank’s death sentence to life in prison.

The people of Georgia were enraged to a fever pitch because of what they perceived as a cowardly appeasement to powerful interests, grotesque betrayal to the oath of office, and conflict of interest.

Governor John Slaton was a part owner and senior partner in the law firm Rosser, Brandon, Slaton, and Phillips (the “Slaton” was Governor John M. Slaton) that had represented Leo Frank during his trial and appeals. The commutation paved the way to Leo Frank’s unusual demise two months later, but the Jewish community would claim the hanging of Frank was because of anti-Semitism.

The Leo Frank case has refused to gather dust over the last one hundred years and has reached a fever pitch in terms of public interest with the double murder centennials (2013 and 2015). One only needs to look at the number of new books or revised editions on the Frank case published in the 21st century for evidence of this trend. The movement to rehabilitate Leo Frank’s image and transform him into a martyr of anti-Semitic injustice is more prominent, widespread, and vocal in the 21st century media than at any other time since the epic saga began in 1913.

All the incidents and details behind the Leo Frank affair offer a glimpse of why it could easily be described as one of the most intriguing criminal cases in the annals of United States legal history.

Sift the Official Records

Most people are unacquainted with the official record of the Georgia Supreme Court files containing the Frank Trial Brief of Evidence (1913) and Leo’s State level appeals (1913, 1914); these documents fortunately survived into the 21st century and are now available online as of October 2010. Even if a great many people were to study these official records, most are not trained on how to properly sift these voluminous legal documents to arrive at the truth. This is why inquiring minds generally depend on dispassionate intellectuals with lucid penetrating eyes to study official legal records of the Leo Frank case, cross reference them, interpret the material facts, and distill them for public consumption.

The Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing

For the average person reading Steve Oney’s breezy and long-winded tome on the Frank case, it’s easy to get the false impression that, for the most part, he attempts to report the relevant and material facts, evidence, and testimony concerning the Leo Frank trial and appeals with a high degree of neutrality and accuracy. However, when one reads all of the published newspaper and magazine articles about or by Steve Oney concerning his position on the Frank case, an entirely different picture is painted about his impartiality. The question one should consider is whether or not Steve Oney’s weltanschauung on the conviction of Leo Frank has interfered with his presentation of the events. Before we can compare And the Dead Shall Rise against the official legal records to determine the reliability of Steve Oney, we should first consider his position on the innocence and guilt of Leo Frank and whether this position or the facts came first.

Steve Oney’s Position on the Leo Frank Case Is Self-Described as Pro Leo Frank (Partisan) and Revisionist

From Wrongly Accused, Falsely Convicted and Wantonly Murdered by Donald Eugene Wilkes, Jr., Professor of Law, University of Georgia School of Law:

Oney’s book (as literary critic Theodore Rosengarten reminds us) does not “come flat out and say who killed Mary [Phagan].” Although the book does assert that the weight of the evidence “strongly suggests Frank’s innocence,” it also claims that “the argument [over whether Frank or Conley is the guilty party]” will “never move beyond that of Conley’s word versus Frank’s.” On the other hand, in a recent press interview Oney stated that “I’m pretty certain that Frank was innocent,” and “I’m 95 percent certain Conley did it.” And in a short magazine article published in March 2004 Oney “declared [his] belief in Frank’s innocence.” (Flag Pole Magazine, Athens, GA, May 5, 2004).

Leo Frank Scholarship Analysis of Steve Oney

The quote above, rewritten half a dozen times, is virtually echoed in nearly every article about or by Steve Oney concerning his position on the Frank case, thus bringing us to a number of conclusions that Steve Oney believes Leo Frank was innocent and wrongfully convicted, framed by Jim Conley (“the real killer”), and unjustly hanged for the strangulation of Mary Phagan.

When one takes a much closer look at the “facts” in Oney’s book used to maintain the integrity of his pro-Frank positions on the case and juxtaposes them against his admitted partisan-revisionist position on the Leo Frank case, he contradicts the grain of official records and decisions rendered by every level of the United States System of Justice. But believing in Leo Frank’s innocence by itself is not what ultimately makes Steve Oney unreliable; its his pretentious act of pretending to be neutral in his book and then misrepresenting, fabricating, and omitting evidence incriminating to Leo Frank. However, the book isn’t completely hopeless. At least Oney was thoughtful enough to wrap his sloppy research in well-written colorful language.

The Unabridged Tabloid-Journalist Thesaurus

Oney’s Leo Frank partisan book is a conglomeration of intensely cherry picked details, which is at times a bit droll and unnecessarily excessive in the amount of immaterial picayune tangents, but on the flipside, he made a huge effort to use a plethora of rich and colorful language from the unabridged tabloid-journalist thesaurus to keep the attention of the reader creatively engaged for the most part.

You can tell Oney makes a real committed effort not to use the same words over and over again as best he could, giving the book an interesting flavor in these regards. In other words, imagine if Shakespeare were genetically hybridized with a seasoned writer from the National Inquirer, and this chimera wrote a long-winded book about a famous criminal case based on sloppy research, fabrications, omissions, and misrepresentations. It would still be interesting to read, even if it did not measure up to college-level academic research standards.

Although Steve Oney is no Shakespeare, he definitely lives up to what you would expect from a seasoned tabloid journalist-author with his well-developed kaleidoscopic lexicon. Despite the unfortunate reality that Oney uses his book as a trash compactor for every erroneous, misrepresented, and fabricated “fact” on behalf of fraudulently exonerating Leo Frank, there are some enjoyable parts throughout his book — an example, Oney’s gay and giggly description of Momma and em clogging in the aisles was vivid and picturesque.

Fact Checking

Carefully reviewing the bibliography, then obtaining and directly examining the sources and references of Steve Oney’s book, reveals that first comes his Leo Frank partisan revisionist conclusions, and then the “facts” are gently massaged, refolded, manipulated, and contoured to support it. The omissions of the most important facts in Leo Frank case from Oney’s book are incorrigible and unforgivable, especially when he spent seventeen years researching his book and had direct access to the 2,500+ pages of surviving and official trial and appeals documents.

Genuine Academic Scholarly Research

Genuine dispassionate researchers cannot stress this point more clearly. Correct scholarly research and historiography requires that first comes the facts and evidence, then the conclusions — not the other way around. Steve Oney’s book does not stand up to minimal scrutiny when examined by dispassionate researchers and will not stand the test of time once more rigorously researched books are eventually published. Ironically, the most accurate book (despite its errors) written on the Leo Frank case was published in 1989, by Mary Phagan Kean, The Murder of Little Mary Phagan.

Fabrication, Misrepresentations, Omissions, and Half-Truths

Despite the book being mostly well-written, Steve Oney is indisputably guilty of making misrepresentations, unsupported claims, and using fabricated evidence that does not stand up to even the most minimal scrutiny in regards to supporting his Leo Frank partisan revisionist position. Even more flabbergasting are the incomprehensible omissions within his book, he geekishly goes into painstaking nanoscopic details on some people, places, and things, but intentionally leaves out volumes of the most important evidence from the official trial and appeal legal records ineluctably damaging or incriminating of Leo Frank. Oney left out the majority of the evidence against Leo Frank that ensured every level of the United States Legal System sustained the verdict of guilt for Frank.

On the flip side, some Leo Frank partisan revisionists could easily argue Steve Oney irredeemably allows too much information into his book that seems to incriminate Leo Frank, but there’s a catch. Even if Steve Oney’s revisionist positions on the Leo Frank case are mostly couched with faux neutrality throughout most of his book, his real position becomes most evident toward the final half, rather than in the beginning of his work. In the last sections of his book, he goes to inordinate lengths to exonerate and thus rehabilitate the image of Leo Frank, even if it means doing so in a manner you would have never expected to be so deviously cunning from a journalist with a reasonably good reputation. Steve Oney’s claim of looking back on the early 20th century case with new eyes is myopic at best.

A Matter of Time

Thanks to the Internet age, no unsubstantiated, misrepresented, or fabricated facts in Oney’s book will be left unexamined, and in due time, every sentence, source, and reference in his book will be checked for its veracity and exposed to the world if erroneous or fraudulent. The final verdict on Steve Oney’s book and his reputation for intellectual honesty will eventually be rendered: no honor, no integrity, no honesty.

Under the Veneer, Steve Oney Is a Pseudo Historian Practicing Pseudo Scholarship

It can’t be stressed enough, this wolf-in-sheep’s-clothing book is written in a style that gives it an air of balanced scholarly neutrality, but when one takes a much closer look at the statements and claims within it, and then compares them against the 2,500+ pages of surviving Leo M. Frank official court case legal documents, one discovers this book by Oney is nothing more than another Jewish con job, just like every other book written by Jews about the case.

The Collective Jewish Pathology of Self-Deception and Paranoid Neurosis Is a Genetic Disease

The Frank case is a high drama that became a permanent part of U.S. legal and social history, in part, because the case of Leo Frank had some of the spiciest ingredients of race conflict, class division, and religious friction all amplified and distorted by the myopic spectacles of Jewish tribal neurosis.

While the case was playing out in State and Federal court system, it transformed into an international Jewish cause celebre that reached as far away as Europe, when its fevered pitch in the U.S. national media spilled outside domestic borders. Even after the lynching of Leo Frank on August 17, 1915, the case never fully died, but slowly evolved into a Jewish mythology that Jews and many leftists believe to be true with religious fanaticism.

The Prosecution of Leo Frank Is the Persecution of Jews

What was nothing more than a heinous crime of passion committed by a frustrated twenty-nine-year-old serial pedophile, who happened to be a high-profile and rising star within Southern Jewish society, was transformed by collective Jewish tribal hysteria, overexaggerating the subtle political, regional, and social overlays, into another permanent schism between Jews and Gentiles.

Leo Frank the Poster Boy of Jewish Neurosis

The dramatized Leo Frank soap opera conjured in the paranoid schizophrenic collective mind of Jews seems to be one of the favorite choices embodying the need to nurture the neurotic and pathological longing to perpetuate Jewish status as noble victims. The victim-persecution pathology is a strong theme that runs high and deep through most of the books written on the Leo Frank case by Jews.

So many books on the Leo Frank case have been written by Jews neurotically obsessed with the case being an anti-Semitic UFO-like galactic conspiracy that, as a byproduct, most non-Jews studying the case think that because so many books take this persecution position, it must be true. However, ultimately, the Leo Frank case is not about a vast anti-Semitic conspiracy by Gentiles, but about a spurned and frustrated pedophile who pounded in the face of a little girl who rejected him. Then he lifted up her dress while she lay on the floor unconscious, ripped open her bloomers, and savagely raped her, and naturally because of the disastrous implications of what he had done, he had no choice but to permanently silence her.

Had Mary Phagan survived the ordeal and reported in explicit details what Leo Frank had done to her in the metal room, every prisoner in the State of Georgia would be fist fighting against each other to determine the pecking order of who got first dibs on eating him alive. Instead of telling the truth, a collective Jewish treasury finances a Leo Frank industry of mind-boggling proportions that has manufactured more than one hundred years of doubt about his guilt, but now with the Internet age and Pax Jewry reaching the end of its peak power, the truth about Leo Frank’s guilt will become inescapable.

Take the Leo Frank challenge, and read the entire 1,800-page official Georgia Supreme Court Case File on Leo Frank and decide for yourself if every level of the United States Appellate Court System was right or wrong in sustaining the Georgia Supreme Courts affirmation of Leo Frank’s guilt.

The Leo Frank Industry

The popularity of Leo Frank has seen a major revival in the years surrounding and after the turn of the 21st century, with new treatments in every kind of creative media format imaginable, including a musical, Parade (1998), with jinglesque catchy songs, a fictionalized docudrama, People vs. Leo Frank (2009), and a plethora of books, all taking “creative artistic license” to the extreme and pushing the envelope of absurdity for the Jewish partisan and revisionist position on the case. After studying all the official legal documents of the Georgia Supreme Court Case File on Leo Frank and then seeing how Jews twist and manipulate the case, you can’t help but understand that the “creative artistic license” taken by Jews on the Leo Frank case is nothing more than insolence to the extreme, blood libel against Gentiles, anti-white and anti-black racism, smears and defamation directed against non-Jews.

Leo Frank, More than a Man, Less than a God

Alas, these Jewish-friendly fictionalized interpretations of the Leo Frank case embody the subversive Jewish Hollywood mockery perpetually at war with Gentile Western civilization. Thus ensuring the mythology of Leo Frank continues his genetic mutation toward the Jewish Übermensch, as he ascends to saintly godhood with the centennial of his martyrdom. Moreover, as a result of the Jewish money-making media circus and blood-money industry surrounding the Jewish beautification of Saint Leo Frank and the defamation campaign against Gentile Western civilization, the Leo Frank case has become another ugly war front in the ongoing multifront Jewish-Gentile culture war, smoldering and raging at the surface for more than a century.

Dishonoring the Life of Mary Phagan

In the wake of the Leo Frank partisan revisionism movement growing since 1913 is a violently beaten, raped, and strangled little thirteen-year-old poverty-stricken white girl, six feet under, who had to drop out of school at the age of ten in 1910, laboring in filthy factories and mills to help her family make ends meet.

Jewish Inbreeding

The selective breeding program of Jewry that reaches back thousands of years made it possible for the Jewish IQ to rise seventeen points above the average. It is this concentration of primitive tribal genes in the Jewish genome that cursed so many Jews with the pathology of extreme racist myopia and self-deception to the degree they would transform a violent and murderous pedophile into a holy icon regarded as a stoic Jewish martyr-hero, who was swept into a vast anti-Semitic conspiracy by Gentiles.

Pretentious Book

A cursory look at the book reveals Steve Oney is no Bernard Lazare (Anti-Semitism: Its History and Causes), capable of emotionally removing himself from the Jewish tribal neurosis artificially created by such a complex and convoluted subject involving one of his racial kinsmen. Steve Oney makes a good effort here and there to present the case through an impartial lens, but ultimately, his crass, pompous, and pretentious ego oozes from too many sentences and chapters in his book, like the low-nutrient transfatty slime that drips down the outer wall from the exhaust fan at the back of urban burger joints.

Seventeen Years in the Making to Write a Book That Fails

Steve Oney claims he spent more than seventeen years dedicated to writing this “magnum opus” on the Leo Frank case. Many people have called his treatment of the most infamous, controversial, and contentious criminal case from the annals of early 20th century Southern legal history the definitive account of the Leo Frank saga. It’s easy to see how the masses of avid readers might assume that because someone wrote and published a long-winded, neural-feigning, and reasonably well-written book on the Leo Frank case, it must be the best source on the topic. For Leo Frank scholars and amateur students of the case, Oney at best gets a C- overall and fails with a solid F when it comes to maintaining fact-checking integrity concerning the evidence he uses to exonerate and rehabilitate Leo Frank.

For students of the Leo Frank case, who have studied more than 2,500+ pages of official Leo M. Frank State and Federal legal case files (1913 to 1915) — dry leaves that have luckily managed to survive beyond 2013 — the reality about Steve Oney’s book is it reads like nothing more than an “…elephantine magazine article…” written in “…slangy journalese…” as Charles Weinstein suggested. The name dropping, boring chapters, and Oney’s ego slime that oozes from the pores of the book probably means half the people who pick up this book will never finish it, and those who complete the book will never do any fact-checking to see if what Oney is saying to exonerate Leo Frank is true.

The Depth of Steve Oney in a Nutshell

The book also reveals that the depth of Steve Oney’s mental capacity for truly insightful analysis is slightly above average at best and partly constipated in the shallow realm of tabloid journalistic reportage. Many people familiar with the voluminous official legal documents of the case feel unsatisfied with the book. Everyone wants to know when the ultimate unpretentious and definitive book on the case will be written by a dispassionate researcher.

From the perspective of a Leo Frank scholar, at times, the two-dimensional analysis Steve Oney provides feels dumbed down and flabby, giving you the impression he lacks the fearless spirit to plumb the depths of the case and soar to greatest heights of a time-traveling eagle looking downward on the case like a dispassionate historian whose mind is free and clear of the shallow, subjective, and egotistical self-deceptions. Steve Oney’s book drives 742 miles with the emergency brake on and does not look at the case one hundred years later with new and lucid eyes, but instead with myopic rose-colored, hexagram-shaped glasses and that’s the bottom line.

The book ultimately provides little historical context of the bigger picture of time and space. As Charles Weinstein (2003) put it, “historian’s skills are needed to contextualize this century-old crime, explore its sectarian and sociological mysteries, and draw out its lasting implications. Unfortunately, author Steve Oney is merely a journalist: his talents begin and end with investigative research and reportage. He explains in exhaustive and often unnecessary detail exactly what happened; he fails to plumb the why.” (Amazon.com Review, November 7, 2003)

The Best Leo Frank Revisionist Book

It seems like the ultimate purpose of Oney’s book is to create the best toned-down rendition of the Jewish revisionist position to exonerate Leo Frank as an innocent scapegoat, framed in a crime committed by his semiliterate Negro pet, James Conley. Way to go, Steve, making lots of money off this dead little girl by feeding the insatiable pathologies endemic of the Jewish community.

Food for Rabid Dogs

At times, Oney’s book is frothing with contempt. One can’t help but envision the hate-filled Jewish community, rubbing its hands, vampire fangs bared and foaming at the mouth from a terminal-stage rabies infection over the book smearing glatt kosher shit everywhere, even on the deceased.

No matter how much time passes from the original event, the Leo Frank case never ceases to capture the imagination of the public, Jew and Gentile.

Time to Check the Facts

Let’s examine a number of unsubstantiated, erroneous, maliciously fabricated, weak, and questionable claims made in Steve Oney’s book, And the Dead Shall Rise: The Murder of Mary Phagan and the Lynching of Leo Frank.

Steve Oney Misquotes Official Legal Records and Documents Concerning Selig Cook, Minola McKnight

Steve Oney misquoted the Selig cook, Minola Mcknight, concerning her reporting Leo Frank came home for lunch on April 26, 1913, at 1:20 p.m. in her June 3, 1913, statement to police, but Minola actually said Leo Frank came home at 1:30 p.m. as documented by the stenographed deposition (BOE, State’s Exhibit J, June 3, 1913).

A simple misquote of ten minutes might seem like a trifling mistake, but throughout the entire month-long trial, differences in mere minutes in the murder timeline became the central focus of gladiatorial battles ferociously fought over between defense and prosecution lawyers. The “mistake” by Steve Oney is in Leo Frank’s favor (of course), shrinking the amount of available Mary Phagan disposal time by ten minutes, and thus making Jim Conley’s description of what happened that afternoon less plausible given the time constriction. In a murder trial where every second of time is precious and crucial to the timeline of the defense and prosecution theories, minutes become immeasurably valuable and can determine the outcome of a case. Every misquote of the official record by Steve Oney in his book is in Leo Frank’s favor, making it seem impossible that they were accidental.

Minola’s June 3, 1913, statement tended to assert Leo Frank left the National Pencil Company at about or just before 1:20 p.m., as it took usually around eight to ten minutes for Leo Frank to get home at 68 East Georgia Avenue, from the NPCo located on 37 to 41 S. Forsyth Street, Atlanta, Georgia. Minola said Leo Frank arrived at 1:30 p.m., ate no lunch, and left the Selig home five minutes later at 1:35 p.m. on April 26, 1913.

Minola’s affidavit raised suspicions about Leo Frank because it left most people wondering why he had no stomach for lunch, especially in light of the fact it also meant that he would have rejected the lunch Minola had specifically prepared for him. Leo Frank alleged he made a phone call to Minola prior to coming home that Saturday. Why would Frank request lunch and then not eat it when he arrived? That’s unusual behavior that raised red flags, then and now. What caused Leo Frank to completely lose his appetite between the time he called Minola to the time he arrived at home?

Pregnancy Hoax: Lucille Selig Frank Pregnant with Leo Max Frank II

Steve Oney quotes a woman who suggested Lucille Selig Frank was pregnant and miscarried in 1913, but none of the voluminous surviving letters written between Lucille and Leo, friends and family, hint at any pregnancy or miscarriage, nor are there any condolences or subtle mentioning of it, not even couched (Koenigsberg, 2010).

The Leo Frank Girl-man Hoax

Author Steve Oney (2003) makes the unsubstantiated claim that Leo Frank was 5’6″ (sixty-six inches) tall, but Frank’s 1908 passport application says he was 5’8″. So which one is more likely right? Steve Oney fabricates Leo Frank’s height to try to make him seem smaller than he really was in reality, thus making it seem less likely he could have assaulted the 4’11” Mary Phagan. This kind sneaky pseudo scholarship is a pervasive theme throughout Oney’s book.

Proof that Leo Frank’s passport application says he was 5’8″: https://www.leofrank.org/images/passport-leo-frank/leo-max-frank-passport-application.jpg. And based on his lean muscular build (muscle weighs more than fat), he more likely weighed around 155 lbs. or more. Research at Cornell University in Ithaca, NY, clearly indicates Leo Frank played on the college basketball team and also regularly played tennis on the college squad. Oney attempts to turn Leo Frank from a formerly fit basketball and tennis athlete into a petite Auschwitz muscle wasting skeleton in the last stages of terminal AIDS. With Steve Oney, first comes the conclusions and then the facts massaged to fit them.

How Could Sweet Little Leo Frank Attack Mary Anne Phagan?

It’s not just Steve Oney who plays these games with rewriting history. Other pseudo historians try to downplay Leo Frank as the physical product of a college athlete who continued to play tennis regularly after college. The attempts to make Frank seem much smaller and thinner than he really was became part of the historically manufactured evidence on his behalf, finally upgraded into mutual consensus and finally transformed into “fact” by Leo Frank partisans. The goal was to make Frank seem less threatening in size and strength, and thus less likely to have attacked Mary Phagan if he was too weak.

Leo Frank Auschwitz Victim

So Steve Oney is not the only one who manufactured the image of Leo Frank as a short, rail-thin, petite, and frail girly man. It’s every Leo Frank partisan and revisionist. Part of the false image created by Leo Frank partisans is to make it seem less likely Leo Frank could have committed the crime with the image conjured up of Frank as a little nebbish Jewish pencil neck geek, instead of the fit, lean muscle mass college athlete (1902 to 1906) and the active tennis player within Southern Jewish Society (1908 to 1913). Could a short Auschwitz skeleton overpower Mary Phagan? No way, but a fit college athlete at 5’8″ could easily subdue a 4’11” chunky little thirteen-year-old.

Leo Frank Partisans Quote Each Other

Most prominent Leo Frank partisan authors requote each other ad nauseum until the case becomes a cacophony of half-truths. Moreover, most authors who write on the Leo Frank case make gratuitous claims about him without ever bothering to do original research and check the veracity of the original references and sources, which tend to provide more accurate information.

Steve Oney Tones Down Some of the Garbage In and Garbage Out

The sloppy research published and requoted by Leo Frank authors like Steve Oney is the most common theme of their books, magazine and newspaper articles, and films, second to their claims that Leo Frank was the fall guy over the heinous Mary Phagan murder, because a guilty Negro was not worthy enough in terms of his blood value for paying the ultimate price over a dead white girl. In other words, one of the reasons Jew Leo Frank was convicted and hanged was because a Negro was not as worthy as a Jew to pay the ultimate price for the murder of Mary Phagan. Though this is a common theme amongst Leo Frank revisionists, Oney tones his book down for the mainstream, not just Jews, and steers away from this claim, unlike Alphin.

Third, all Leo Frank partisans contend the crime against Mary Phagan was actually committed by the diabolical semiliterate Negro sweeper, Jim Conley, who duped the White man and every level of the U.S. judicial system.

Finally, the ugly Jewish blood libel, Leo Frank partisan writers posit, is the Frank case was a 1913 to 1915 intergalactic conspiracy enforced and made possible as a result of the widespread white Gentile anti-Semitic culture and media frenzies at the beginning of the investigation.

Not One Jewish Source from 1913 to 2010 Mentions Leo Frank’s Passport Application

Why the refusal to go back to 1907/1908 government registered documents, when Leo Frank was pre-enabling one of the most important chapters in his life, a European sojourn to royalty-aristocratic controlled Magna Europa, to visit his father Rudolph’s “Ancestral Homeland,” the German Empire, where some of the world’s best engineers are born, created, educated, and reengineered. The training at Eberhard Faber in Germany may have been a part of ensuring it was not luck that the National Pencil Company grew up and became successful under the tutelage of innately intelligent Leo Frank.

It will be interesting to see how the Leo Frank girl-man hoax will be perpetuated or revised, now that it has been exposed here and now, 2010, on the Leo Frank Research Library.

Relativity Is the Most important Factor, Not Leo Frank’s Height

Leo Frank was significantly larger and more powerful when compared against Mary Anne Phagan, who was described by one of her former co-workers at the Leo Frank trial, as a “Low chunky girl” (BOE, 1913). The “blubbery” Mary Phagan (1899 to 1913) was only 4’11” (Phagan, 1987), weighing 115 to 120 lbs. At 5’8″ and the fit tennis athlete Leo Frank based on his build was likely around 155 lbs.

Within the official record, Mary Phagan is described as well developed, heavy (Mrs. Coleman, BOE, July, 1913), (“Fat”), and Leo Frank is muscle fit with records of his athletics to back it up (Cornell, 1902 to 1906) and pictures showing him years later still looking fit.

Leo Frank and Mary Phagan Height Difference: Seven to Nine Inches

Giving credence to the erroneous claims, Leo Frank “on the low end” of his height scale was at 5’6″ (sixty-six inches), which was seven inches taller than Mary Phagan at 4’11”, and Leo Frank “on the high end” of his height scale at 5’8″ (sixty-eight inches) was nine inches taller than she was. Perhaps Leo Frank wore one-inch man-heals, which would have given him the appearance of being 5’9″ (sixty-nine inches).

Leo Frank’s size difference in terms of how much bigger and stronger he was than Mary Phagan is where the truth of his capacity in being able to overpower her without a scratch on him becomes apparent.

Mary’s Hourly Wages

Steve Oney incorrectly says Mary Phagan made ten cents an hour; actually, she made 7 4/11 cents an hour, or $4.05 a week for a fifty-five hour workweek (Coroner’s Inquest, Former Paymaster J. M. Gantt, May, 1913).

Why Nitpick over Such Trivial Pennies?

It’s hard to imagine that pennies were so valuable back in the early 20th century. That was, of course, before the independent Federal Reserve, born in 1913, could slowly erase the value of U.S. currency over the years and decades by 99% of its value, up to, through, and beyond 2013, until the dollar will eventually collapse from overprinting in the near future. Pennies were actually not so trivial back in 1913. In terms of their ability to sustain a family, for instance, they were “equivalent” roughly to U.S. dollars — “green backs” — after adjusting for inflation by 2013 standards.

Back in 1913, pennies were quite a big deal. You could buy a fresh loaf of warm bread right out of the oven for one to two cents. At a typical dive bar, a pint of beer or a shot of whiskey was three to five cents. Five to ten cents would get you a nice lunch. Today a loaf of bread is $2 or more at a typical “run of the mill” grocery store, and at a dive bar in Atlanta, a beer is typically $3 to $5, and a shot of whiskey on the rocks $3 to $5. You can get a decent lunch in Atlanta for $5 to $10 too. These prices are more or less about right anywhere you go in the United States in 2013, barring lunch and drink specials. The price of a loaf of bread over the last one hundred years is a good indicator of monetary value in the USA.

The importance of getting Mary Phagan’s 7 4/11 cents an hour wage correct is because of the cozy relationship Leo Frank had with James “Jim” Conley. Jim was being paid eleven cents an hour or $6.05 a week (nearly 50% more than the individual 170+ laborers making up nearly the entire workforce).

Neutral observers are asking, why was a Negro janitor, Jim Conley, in the white racial separatist South of Jim Crow Laws in the Progressive Era, whose job was to sweep the floors, making a lot more money, relatively speaking, than the average laborers whose jobs were so critically important to the company’s production and bottom line? It suggests that perhaps Jim Conley was more than meets the eye in terms of his value at the factory under the General Superintendent Leo M. Frank, and perhaps the Negro roustabout served other more important functions for Frank.

The shockingly high eleven cents an hour Conley made for sweeping the factory floors tends to suggest that maybe Jim Conley was Leo Frank’s special watchdog after all, because it is hard to imagine a legitimate reason why a job warranting only five cents an hour at the time was compensated for at more than double its fair market value. Not to mention, Jim Conley was allegedly also getting some nice tips for watching on the side (Jim Conley, August 4, BOE, 1913).

At the trial, one of the young female employees testified that there were complaints of Jim Conley “sprinkling” (urinating) on the pencils. If the substance of the statement were true, most neutral observers would ask why a Negro janitor who was relieving himself on the pencils be allowed to stay at the factory, when Negro replacements were a dime a dozen. It could have been just a rumor to mock the generally disliked beer-scum-stinking janitor, and that little tidbit of information is really only important in light of the fact that Jim Conley was also given allowances in not always having to punch his time card in the clock. Not having to always punch the time clock was a privileged likely not extended to many employees. Why was Leo Frank managing Jim Conley’s numerous watch contracts? Conley was running a watch concession at the factory. The cozy relationship between Leo Frank and Jim Conley, the circumstances of certain punch clock liberties, and pay rate issues concerning Jim Conley tends to sustain Jim was more important to Frank than meets the eye and corroborates Conley’s statements that he served Frank as more than just a sweeper.

The Origin of the Leo M. Frank Teeth X-Ray and Mary Phagan Bite Mark Hoax

To Number Our Days, Published in 1964 by Dutch Jew and self-proclaimed Zionist Pierre van Paassen. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 64-13633. 404 pages.

To Number Our Days, “Short Stand in Dixieland,” pages 237-238

The Jewish community of Atlanta at that time seemed to live under a cloud. Several years previously one of its members, Leo Frank, had been lynched as he was being transferred from the Fulton Tower Prison in Atlanta to Milledgeville for trial on a charge of having raped and murdered a little girl in his warehouse which stood right opposite the Constitution building. Many Jewish citizens who recalled the lynching were unanimous in assuring me that Frank was innocent of the crime.

I took reading all the evidence pro and con in the record department at the courthouse. Before long I came upon an envelope containing a sheaf of papers and a number of X-ray photographs showing teeth indentures. The murdered girl had been bitten on the left shoulder and neck before being strangled. But the X-ray photos of the teeth marks on her body did not correspond with Leo Frank’s set of teeth of which several photos were included. If those photos had been published at the time of the murder, as they should have been, the lynching would probably not have taken place.

Though, as I said, the man died several years before, it was too late, I thought, to rehabilitate his memory and perhaps restore the good name of his family. I showed Clark Howell the evidence establishing Frank’s innocence and asked permission to run a series of articles dealing with the case and especially with the evidence just uncovered. Mr. Howell immediately concurred, but the most prominent Jewish lawyer in the city, Mr. Harry Alexander, whom I consulted with a view to have him present the evidence to the grand jury, demurred. He said Frank had not even been tried. Hence no new trial could be requested. Moreover, the Jewish community in its entirety still felt nervous about the incident. If I wrote the articles old resentments might be stirred up and, who knows some of the unknown lynchers might recognize themselves as participants in my description of the lynching. It was better, Mr. Alexander thought, to leave sleeping lions alone. Some local rabbis were drawn into the discussion and they actually pleaded with Clark Howell to stop me from reviving interest in the Frank case as this was bound to have evil repercussions on the Jewish community.

That someone had blabbed out of school became quite evident when I received a printed warning saying: “Lay off the Frank case if you want to keep healthy.” The unsigned warning was reinforced one night, or rather, early one morning when I was driving home. A large automobile drove up alongside of me and forced me into the track of a fast-moving streetcar coming from the opposite direction. My car was demolished, but I escaped without a scratch….

Reference:

To Number Our Days, Published in 1964 by Pierre van Paassen. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 64-13633. 404 pages.

Were Dental X-rays of Leo Frank’s Teeth Ever Taken because of Bite Marks Found on Mary Phagan during Her Numerous Autopsies?

In Steve Oney’s book, And The Dead Shall Rise: The Murder of Mary Phagan and the Lynching of Leo Frank, he claims there were x-rays of Leo Frank’s teeth taken for the purpose of comparing them to bite marks found on the body of Mary Phagan. The supposition is to determine if Leo Frank was innocent of the murder or not, with the idea that whoever bit up Mary Phagan’s body was likely the murderer. It certainly would be enough to convict someone.

In the 2,500+ pages of surviving legal documents on the Leo Frank case (1913 to 1915) contained in several government archives, including the Georgia State Archive, United States District Court Archives, and United States Supreme Court archives, there is ABSOLUTELY nothing mentioned ANYWHERE about any kind of X-rays performed on anyone, not performed on Leo Frank or Mary Phagan, and there is absolutely nothing mentioned about bite marks on Mary Phagan in any affidavits, trial testimony, autopsy reports (defense and prosecution), or evidence submitted at Frank’s trial July 28 to August 26, 1913, appeals (1913 to 1915), commutation (June 21, 1915), or pardon without exoneration (March 1986). From a scientific point of view, X-ray technology was in its infancy by the time 1913 rolled around and was not in any measure of widespread use.

Is the Leo Frank X-Ray and Mary Phagan Bite Mark Claims Another Hoax?

Within the thousands of pages of surviving records on the Frank case, there is nothing specifically in the 1,800-page Leo M. Frank Georgia Supreme Court Case file about Leo Frank having his teeth X-rayed or Mary Phagan having visible bite marks on her, or even Mary Phagan being X-rayed because of alleged bite marks. The Leo M. Frank Georgia Supreme Court case files dealt directly with the trial testimony, facts, autopsy reports, and evidence, making it the likely place such erroneous claims might be documented. However, an exhaustive review reveals there is absolutely nothing, not even a sentence or word about Leo Frank’s teeth being X-rayed in any Georgia Superior Court or Georgia Supreme Court case documents from 1913 to 1915. An exhaustive check of historical newspapers from 1913 to 1915, reveals nothing about Leo Frank’s teeth getting X-rayed, or bite marks found on Mary Phagan or an X-ray performed on Mary Phagan in any of the three major Georgian newspapers at the time: Atlanta Journal, Atlanta Constitution, and Atlanta Georgian (1913 to 1915). Even a search of prominent newspapers outside of Georgia, including The New York Times (1913 to 1915), which admittedly took the side of Leo M. Frank, does not mention dental or autopsy X-rays.

The point is absolutely nothing supports Leo Frank’s teeth being X-rayed as part of the Phagan murder investigation, trial, appeals, or commutation. No evidence supports that Mary Phagan was X-rayed for bite marks, and nothing suggests Mary Phagan had any VISIBLE bite marks all over her body from either prosecution or defense physicians who performed their numerous autopsies.

There was, however, a report in the Leo M. Frank Georgia Supreme Court case file (see folder 2) about a little teenage girl that formerly worked at the factory claiming Leo Frank turned her out and possibly inseminated her. She claimed Leo Frank was into sadist biting, and during sex, he bit her and left a serious bruise on her inner thigh. Perhaps Steve Oney twisted this affidavit and negative tidbit of information for the benefit of Leo Frank, and maybe he thought the 2,500+ page official surviving record of the Leo M. Frank case file would NEVER make it onto the Internet for the whole world to see.

The report about Leo Frank turning out another little girl (not Mary Phagan), seducing her, possibly impregnating her, and afterward biting her inner thigh was more about showing the kinky, sadistic propensities Frank had as part of his sexual appetite, and nineteen girls, former employees, at the trial, provided short and to the point testimony that revealed he had a bad character for lasciviousness. The defense didn’t dare cross question these girls out of fear of the intimate details. Either way, Leo Frank was essentially painted as an aggressive sexual predator and pedophile toward some of the girls at the factory, to translate a “bad character for lasciviousness.” The point of all that evidence was Dorsey’s way of trying to build a bridge, showing a clear pattern of behavior about Leo Frank supporting the notion he was more likely to have had a hand in the murder of Mary Phagan because of what her discovery revealed happened to her and the implications of it at the time.

Regarding X-rays, while the concept was first invented “by the German scientist Wilhelm Roentgen (1845-1923) in 1895,” they weren’t used for medical purposes until 1913:

“In 1913 the first X-ray tube designed specifically for medical purposes was developed by American chemist William Coolidge (1873-1975).”

The thought of a process that was just created being used in this trial is a bit farfetched, to say the least. Read more: X-ray Machine — used, first, body, produced, device, Medical Use of X-rays, What Are X-rays? Modern X-Ray Machines http://www.discoveriesinmedicine.com/To-Z/X-ray-Machine.html

I doubt if the court would’ve even allowed such evidence given the technology was in its infancy, not that it would’ve proved the case any better than a physical mold. A simple caste of the teeth in comparison to “bite-marks,” if they existed, could have been made, if the defense sought to prove his innocence on such evidence. However, there were no bite marks on Mary Phagan, according to every surviving legal document or newspaper, including defense witness medical doctors who provided trial testimony. Why would Steve Oney, who claims to have studied the Leo Frank case for seventeen years, perpetuate such lies that amount to fabricated evidence? Now, because the Leo Frank X-Ray hoax is mentioned in nearly every Jewish rendition of the Leo Frank case, it can accurately be called a Jewish hoax! To determine whether Steve Oney (2003) is lying and perpetuating a Jewish hoax, simply review the 2,500 surviving pages of the Leo M. Frank legal documents and the hundreds of pages of newspapers articles from 1913 to 1915. The result? ABSOLUTE ZERO, nothing, is mentioned about X-rays or bite marks on Mary Phagan.

When you review the official 318-page Leo M. Frank brief of evidence:

Do you see anything about X-rays of Leo Frank’s teeth? No.

Do you see anything about bite marks on Mary Phagan? No.

Do you see anything about X-rays done to Mary Phagan? No.

Is there anything in the Defense Physician Autopsy Reports about bite marks on Mary Phagan? No.

Is there anything in the Prosecution Physician Autopsy Reports about bite marks on Mary Phagan? No.

Guess Who Started the Jewish X-Ray Leo M. Frank Hoax?

A self-described Zionist Jew in 1922 named Pierre van Paassen and the Frankites have been parroting him ever since.

Look what happens when tabloid pseudo scholars and liars like Steve Oney publish outright lies and baloney on the Frank case. It causes people to think Leo Frank was framed. So in one sense, Steve Oney achieved his goal, of helping to perpetuate a hoax and fraud to the benefit of Leo Frank.

John Marshal Slaton Commutation Order

The John Marshal Slaton twenty-nine-page commutation order published June 21, 1915, reviews and mangles the facts, evidence, and testimony in the Leo M. Frank case, pretending to bring forward new facts that emerged from 1913 to 1915. After reviewing the twenty-nine-page clemency order, do you see anything about Leo Frank’s teeth X-rayed in there or Mary Phagan being X-rayed because of bite marks found on her body? No.

Leo Frank’s Four-Hour Statement at His Trial

Does Leo Frank mention anything about his teeth being X-rayed or bite marks on Mary Phagan during his four-hour statement to the judge and jury? Or during his two years of appeal? No.

The tabloid journalist Steve Oney is full of baloney concerning his Leo M. Frank X-ray hoax. Oney fabricated or perpetuated a lot of other evidence as well in his book. We found dozens of errors, but we will just focus on the main stuff.

Steve Oney Says: MOSES FRANK — Confederate Veteran Moses Frank

Allen Koenigsberg (2011) writes:

Almost without exception, every book on the case (Golden, Connolly, Frey, Melnick, Oney) has referred to the “thin gray line” and stated that Leo’s “interested” uncle was himself once a Confederate soldier. However, extensive research reveals that Moses Frank never served in the US military, North or South, nor do any of his obituaries or eulogies (1841-1927) mention such a record despite a much later family belief. Moses Frank, an 1856 immigrant from Dudelsheim in Hesse-Darmstadt, had lived in Atlanta, on and off, since 1866 (when he married his first wife Jane Wilson Kelly), and had even been in that city the very week of April 21st (with his second wife Sara) – why was he being kept up to date so carefully about this regular annual event (“Today was Yondeff”)? Moses was about 72 at the time and would hardly need to be reminded of his own mortality (“smaller each year”)? In a Mar. 1914 jail-house interview, Leo Frank would not say that his wealthy uncle was a Confederate veteran, nor was this possibility ever broached at the Trial (it was suddenly offered – without proof – only in Oct. 1913, by Reuben Arnold). The location of that handwritten original, though shown in Court, is unknown and no photographic image of it survives. Solicitor Dorsey implied to the jury that this “exculpatory” letter was not sent at its apparent date or time, an issue entirely ignored in the extensive Leo Frank literature. Curiously, no one at the Trial (or later) ever referred to the fact, or the reason, that his uncle had been blind since 1907. And despite the mistaken claim of his presence in the Frey book (‘The Silent and the Damned’), Moses Frank was continuously absent from Atlanta for over 3 years (Apr 21, 1913 – Oct 1, 1916). However, his exact whereabouts between Apr. 28 and mid-Sept of 1913, is still unresolved; he and his wife Sara were ‘unavailable’ for the Trial and Rae Frank alone (in Aug.) said he was already ‘in Europe’ from where she had been sent Leo’s ‘Apr. 26’ letter (the outer envelope from ‘overseas’ was not produced). Moses did not register in Frankfurt until Sept. 15, 1913 and he may have been in Hamburg (with his wife) since May 9th. (http://www.leofrankcase.com, Leo Frank Case – Open or Closed? 2011)

Jim Conley’s Education

Oney makes errors on Jim Conley’s education, giving him more credit than he deserves.

Perhaps the reason Oney (2003) fabricates evidence and twists the case to benefit Leo Frank is revealed in the fact he pretends the star witness Monteen Stover was not important.

From Wrongly Accused, Falsely Convicted and Wantonly Murdered by Donald E. Wilkes, Jr., Professor of Law, University of Georgia School of Law

Oney’s book (as literary critic Theodore Rosengarten reminds us) does not “come flat out and say who killed Mary [Phagan].” Although the book does assert that the weight of the evidence “strongly suggests Frank’s innocence,” it also claims that “the argument [over whether Frank or Conley is the guilty party]” will “never move beyond that of Conley’s word versus Frank’s.” On the other hand, in a recent press interview Oney stated that “I’m pretty certain that Frank was innocent,” and “I’m 95 percent certain Conley did it.” And in a short magazine article published in March 2004 Oney “declared [his] belief in Frank’s innocence.” (Wilkes)

Although Wrongly Accused, Falsely Convicted and Wantonly Murdered, by Donald E. Wilkes, Jr., Professor of Law, University of Georgia School of Law, makes a convincing case on behalf of Leo M. Frank, it is yet another document written by a Jew and diehard Frankite filled with countless errors.

It seems that every thing ever produced claiming Leo Frank was innocent is filled with nothing but lies and fabrications.

Another perspective from Steve Oney…

Questions and Answers: With Steve Oney

February 5, 2004

By David Finnigan

http://www.jewishjournal.com/arts/article/q_and_a_with_steve_oney_20040206/

Los Angeles writer Steve Oney’s book, “And the Dead Shall Rise” (Pantheon Books, 2003), details two infamous, unsolved crimes: the 1913 murder of non-Jewish preteen Mary Phagan in an Atlanta factory and the arrest, trial, conviction, death sentence commutation and 1915 abduction and lynching by a 25-man mob of Leo Frank, the factory’s Jewish, 29-year-old Northern-born supervisor. In 1995, on the 80th yahrtzeit of Frank’s death, Temple Kol Emeth in Marietta, Ga., helped place a plaque on the building built on the spot where the tree used to lynch him grew. Oney, a 49-year-old former Atlanta Journal-Constitution reporter, whose wife is Jewish, spent 17 years researching the 742-page book.

Jewish Journal: This book genuinely seems to have taken a chunk out of you as a writer and as a person.

Steve Oney: If somebody had told me I was going to spend 17 years on this book when I got started, I would have quit — immediately. The deeper I got into it, the more entranced I was by the subject; this double-murder mystery, two unsolved killings, the murder of Mary Phagan and the lynching of Leo Frank. So, yeah, it was a chunk of my life. But I don’t know how I could have spent it better.

JJ: Were you trying to give this case, journalistically speaking, a proper, dignified burial?

SO: I took it as a point of pride to get the truth of who lynched Leo Frank. He was the most celebrated convict in America; he was in the state prison, and he was abducted from the state prison without a shot being fired. And then after abducting Frank, these 25 [lynch-mob members] drove by circuitous routes over 150 miles on unpaved roads in Model Ts and lynched Frank the next day at dawn. Not a one of them was arrested or even inconvenienced.

JJ: There’s a body of Leo Frank literature and writing that most people don’t know about; why is there so much of it?

SO: Well, the material is so inherently dramatic. A little girl, Mary Phagan, beautiful, busty, murdered on Confederate Memorial Day, 1913, in a society that is in transition from the old South to the new South. Her boss, a Northern Jew named Leo Frank, convicted of her murder and then lynched — and out of that lynching rose … the modern Ku Klux Klan, and it galvanizes the Anti-Defamation League.

JJ: Do you think it was romanticized?

SO: In many of the previous accounts of this case, there’s the inevitable section where the writer will say, “Outside the courthouse where Leo Frank was tried, people yelled, ‘Hang the Jew or we’ll hang you!'” In my book I say it didn’t happen. It was something that someone wrote a couple years after the crime, and then it got stuck into subsequent recountings of the story.

JJ: I was specifically fascinated by your use of the term, “Negro.” You use it not in quotes and not in italics, but as a common term in parts of the book. What made you choose that term?

SO: I agonized over that choice. Frank was convicted largely on the testimony of a black, self-confessed accomplice named Jim Conley. For one of the first times ever in a capital murder case in America, especially in the South, an all-white jury accepted a black man’s word over a white man’s word. I thought I could never express how stunning a fact that was if I used polite terminology of today. I had to situate you back in the South of 1913 to make you feel what the racial tension was like and to make you see through the use of the word, Negro, how all white people would view a black man at that moment. Even with that rationale, I agonized over it. I can’t impose the polite parlance of contemporary usage on the time. So that’s why I decided to use the word, Negro.

JJ: Many of the Atlanta Jews, in the fallout of the entire tragedy, leave Atlanta, but they stay in the South, as opposed to some of the [non-Jewish] characters who move north. Didn’t that strike you as odd?

SO: Southern Jews are Southerners and Jews second, or they’re both simultaneously. But they are as wed to the land and to the Southern way of life as any Southern [non-Jew]. The Jews of Atlanta in particular, the German Jews into which Leo Frank married, they fought for the Confederacy or their forebearers did. They were very much Southern patriots and that was, on the one hand, why they stayed, on the other hand, why Frank’s lynching was such a shock to them. They stayed, but they nursed very quietly this grievous wound.

By Steve Oney, Tuesday, November 3, 2009

On Aug. 17, 1915, Leo Frank, a Cornell-educated Jewish industrialist, was lynched just outside Atlanta. The atrocity marked the culmination of an ugly conflict that began with the 1913 murder of a child laborer named Mary Phagan, who toiled for pennies an hour in Atlanta’s National Pencil Factory.

Frank, the plant superintendent, was convicted of the crime and sentenced to death, although he always maintained his innocence.

He appealed his case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, losing each time, whereupon Georgia Gov. John Slaton commuted his sentence to life imprisonment.

The decision so angered the general populace that a mob organized by a Superior Court judge, the son of a U.S. senator and a former governor abducted Frank from a well-guarded state prison and hanged him from an oak tree.

The lynching of Frank seems like an incident out of another America, one of gray-bearded Civil War veterans and Jim Crow, Model Ts and ragtime.

Woodrow Wilson was president. “The Birth of a Nation” was playing in movie theaters.

The story, however, remains very much alive. “Parade,” the Alfred Uhry musical inspired by the affair, has been drawing crowds to Los Angeles’ Mark Taper Forum. In November, PBS stations will broadcast “The People v. Leo Frank,” the first full-length documentary to explore the topic.

There are many reasons why the Frank case continues to command attention.

For one, both the murder of Mary Phagan and the lynching of Leo Frank are crimes as puzzling as any Arthur Conan Doyle ever invented. Strange notes, racial paradoxes (an all-white jury convicted the factory boss on the testimony of a black witness) and an intricate conspiracy played a part

But finally the story is still relevant and intriguing because the conflict at its core foreshadows today’s red-state/blue-state hostilities.

The raw material for class warfare was, of course, there from the start — a lovely Southern girl found murdered at a business run by a Northern Jew.

But it wasn’t until after Frank’s conviction that matters exploded. At the urging of the rabbi of Atlanta’s Reform synagogue, a nationwide campaign to exonerate the condemned man was inaugurated by Adolph Ochs, publisher of The New York Times, and A.D. Lasker, the advertising genius behind Sunkist orange juice and Lucky Strike cigarettes. They believed that Frank had not been so much prosecuted as persecuted.

To attract attention to what he viewed as an injustice, Ochs launched the Times’ first — and to this day only — journalistic crusade.

Over an 18-month period, the paper published not just dozens of editorials demanding a new trial for Frank but scores of news articles slanted in his favor.

For his part, Lasker orchestrated public relations stunts and hired William Burns, the private detective who solved the 1910 bombing of the Los Angeles Times, to turn up new evidence.

Although Ochs and Lasker were convinced that anti-Semitism had poisoned Frank’s trial, they and their supporters in New York and other urban areas did not take into account how their efforts would come across in the South or in working-class heartland neighborhoods.

Articulating the populist response was future U.S. Sen. Tom Watson, a Georgia lawyer and polemicist of such superior rhetorical gifts and inexhaustible vitriol that Rush Limbaugh and Glenn Beck pale in comparison.

Week after week in his widely circulated paper, the Jeffersonian, Watson rebutted Ochs and Lasker, arguing to his vast readership that self-appointed elites representing money and privilege had decreed that a child laborer’s life was not equal in value to that of a Jewish industrialist.

“The agrarian rebel,” as historian C. Vann Woodward dubbed Watson, gave voice to a constituency that felt excluded from the halls of power in Washington and on Wall Street. When Slaton commuted Frank’s sentence, Watson called for the lynching.

No one involved in Frank’s death was ever convicted or even indicted. (The chief prosecutor of Cobb County, where the incident occurred, helped to plan it.) The polarizing impact of the affair made itself felt almost immediately.

On Thanksgiving eve 1915, a few months after Frank was hanged, the Ku Klux Klan held its first modern-era cross-burning atop Stone Mountain, several miles east of Atlanta. (Three members of the lynching party were present.)

Meanwhile, the Anti-Defamation League, which had been founded in 1913, took up the fight against religious intolerance in earnest.

The Frank case, however, was about more than racism and anti-Semitism.

It was also about the conflicting perceptions of the nation’s haves and have-nots, the chasm between the people who appear to run things and those who feel they lack a say.

While it’s doubtful that a mob could break into a state prison in 2009 and lynch an inmate, it’s not difficult to imagine a scenario in which something almost as bad transpired.

In an era of escalating home foreclosures and rocketing unemployment, endless bank bailouts and hefty bonuses to Goldman Sachs traders, the Frank saga says as much about current events as it does about history.

Steve Oney, author of “And the Dead Shall Rise,” is chief consultant to “The People v. Leo Frank.”

http://www.ajc.com/opinion/leo-frank-saga-still-185064.html

Next: Steve Oney: Off the Shelf: Letting go of a life’s work (January 10, 2010)

Writer Steve Oney spent decades researching the 1913 murder of Mary Phagan and the subsequent lynching of Leo Frank, but his voluminous files now belong to history.

By Steve Oney

January 10, 2010

With emotions wavering between relief and regret, I remove a battered spiral notebook from a metal file cabinet and place it in an acid-free cardboard box open on my office floor. The notebook contains an interview I conducted in December 1984 at a VA hospital in Johnson City, Tenn., with 85-year-old Alonzo Mann. Some seven decades earlier, he told me, he’d seen a murderer carrying a girl’s body through the lobby of an Atlanta factory, but he was only 14 and too scared to call the police. As a result, an innocent industrialist was convicted of the crime and later lynched.

Mann’s assertion goes to the heart of an enduring debate about a great historical mystery. To me, however, the notebook possesses more than just documentary value. It contains the first research I conducted on a project that consumed nearly half my life.

Six years after the publication of “And the Dead Shall Rise,” my book about the 1913 murder of Mary Phagan and the subsequent lynching of Leo Frank, I am packing my papers for donation to the Georgia Historical Society. The contents of a dozen bulging plastic bins and six overflowing file drawers must be indexed, then placed in the cartons that will carry them from Los Angeles to their new home: Hodgson Hall, an 1875 athenaeum just off Savannah’s live-oak-canopied Forsyth Park.

This is a tedious task, but what makes it more than simply time consuming is that every item conjures intense memories. There go a half-dozen file folders containing notes from tearful conversations with the children of the men who lynched Frank. A bundle of original letters and legal documents recalls its generous source: the now-dead son of a lawyer involved in the case. Dog-eared pages from an Atlanta phone book might not seem significant, but they’re links to the next of kin of a key witness, as well as reminders of the many calls I made trying to track him down. As for the stacks of Xeroxed newspaper stories, they bring back the countless hours I sat staring at microfilm machines in libraries across the country, hoping that by sheer dint of concentration I could summon the past.

Taken together, these materials might well serve as the basis for an exhibit on a kind of research no one in their right mind will ever again conduct. Working without scanners or flash drives, I relied on anachronistic devices and a willingness to camp out in archives for weeks. I ran off most of my newspaper copies on wet process printers, some set for negative film (black print on white background) and others for positive (white print on black background). At university special-collections departments, I took notes with stubby pencils while wearing white gloves.

The piece de resistance is my card filing system. Using 3-by-5 color-keyed cards organized by hand-labeled tabs — “Debate RE rape,” reads one, “Writ of Habeas Corpus,” another — I ultimately filled four shoe-box-sized, marble-paper-covered boxes of the sort favored by graduate students of another era. In my best moments, I think this is the stuff of a magnificent obsession. In my worst, I merely shake my head.

My putative rationale for holding onto everything has been that I’ve been serving as the consultant for “The People v. Leo Frank,” a 2009 PBS documentary inspired by “And the Dead Shall Rise.” The filmmaker and I have needed the papers for fact-checking purposes. But if this is true as far as it goes — director Ben Loeterman and I have spent a lot of time rifling my files — the real reason has less to do with the material’s continuing utility than with my fear of letting it go. During the nearly 20 years I spent amassing my files, I’ve grown fond of them, much as numismatists grow fond of their coins. I’ve also taken strength from them. Here is proof that I’ve done the work that allowed me to identify the men who’d perpetrated Frank’s lynching, arguably America’s worst anti-Semitic incident. And yet, for all of this, the papers have also tied me to a project I was finished with, which is a bad thing.

As I place the last of the files in the acid-free boxes, I realize I am rolling away a stone that for too long has impeded my future. Getting the material out of the office will allow me to move forward. Furthermore, not only do the papers belong in Georgia, where most of the events they describe transpired, but now they will be accessible to generations of scholars, which is reassuring, as the Frank case remains a topic of genuine fascination.

The story is rife with conundrums and rich with meaning. An all-white jury convicted Frank largely on the testimony of a black man — unheard of in the Jim Crow South. Adolph Ochs, publisher of the New York Times, compromised his newspaper’s objectivity in an attempt to exonerate Frank. Both the Anti-Defamation League and the modern Ku Klux Klan grew out of the affair.

Ticking off these facts, I feel a pang. How am I going to get along without my files? This is the material of a lifetime. But then again, as Todd Groce, president of the Georgia Historical Society, has told me: “Remember, you can come visit all of it any time you want.”

Oney is the author of “And the Dead Shall Rise: The Murder of Mary Phagan and the Lynching of Leo Frank.”

Copyright © 2012, Los Angeles Times

Source: http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/news/arts/la-caw-off-the-shelf10-2010jan10,0,4242686.story

References

Van Paassen, Pierre. To Number Our Days. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1964.

Oney, Steve. The Dead Shall Rise: The Murder of Mary Phagan and the Lynching of Leo Frank. New York: Pantheon Books, 2003. Available in Adobe PDF format or order the book at Amazon.com.

See: Leo M. Frank Georgia Supreme Court Case File (1,800 Images Volumes 1 and 2).

Testimony of Jim Conley: https://www.leofrank.org/jim-conley-august-4-5-6/.

Donald E. Wilkes, Jr., Steve Oney, and many other revisionist authors incorrectly describe Leo Frank as 5’6″. The purpose is to make Leo Frank seem smaller and weaker than he really was to make it seem less likely he could have been capable of beating, raping, and strangling Mary Phagan. Rarely do these revisionist writers point out the fact Mary Anne Phagan was about 4’11”. To do so would defeat the purpose of making Leo Frank seem smaller than he really was in real life, because with the knowledge of the physical size of both Leo Frank and Mary Phagan, it becomes clear Frank could have easily overpowered Phagan. Leo Frank at 5’6″ no longer appears as the revisionist version of a petite girly-man incapable of committing the crime, when one becomes aware the twenty-nine-year-old factory superintendent was seven inches taller than the thirteen-year-old little girl at 4’11”. However, the truth of the matter is that Leo Frank was not 5’6″ tall. His official passport application has him measured at 5’8″ (https://www.leofrank.org/images/passport-leo-frank/leo-max-frank-passport-application.jpg), and thus based on this, we see the true picture of him nine inches taller than little Mary Phagan. We also know that just as his height is often fabricated by Leo Frank revisionists, they also made his weight much lighter than he really was, saying he was about 130 lbs., but based on his athletic build, he was likely around 155 to 160 lbs. The real Leo Frank was 5’8″ and about 155 lbs. of lean athletic muscle, not the petite version of him at 5’6″ and 130 lbs. The relative difference between the twenty-nine-year-old 5’8″ athlete at 155 lbs. becomes clear against a 4’11” chubby and flabby little teenage white girl who toiled with pencil erases, sitting in her seat for eleven hours a day, fifty-five hours a week, over a total of thirteen months = more than 2,555 hours slaving away at 7 4/11 cents an hour (not the ten to twelve cents an hour Frankites have claimed).

For the first time in more than one hundred years, the centennials of the double strangulation during the years 2013 and 2015, all the lies, fabrications and omissions by the Leo Frank revisionists have been exposed to light. Maybe now after torturing the memory of this little girl and waging a blood libel smear campaign against Southerners and European-Americans for more than a century, it will finally become another battle lost in the Jewish culture war against Western Civilization.

Steve Oney speaks at the People Vs. Leo Frank Round Table: http://www.gpb.org/the-people-v-leo-frank.

The University of Georgia Magazine. Features. March 2004, Vol. 83, No. 4. And the Dead Shall Rise, by Steve Oney. “To produce the definitive book on the 1913 lynching of convicted murderer Leo Frank, the author devoted 17 years of his life—and came to the conclusion that Frank didn’t kill Mary Phagan,” by Steve Oney (ABJ ’79): https://archive.org/details/georgia-magazine-2004-and-the-dead-shall-rise-steve-oney.

Steve Oney on C-Span (October 11, 2003) speaking about his research and book on Leo Frank: http://www.c-spanvideo.org/program/178832-1. Not a word about State’s Exhibit B, Monteen Stover, and Leo Frank’s August 18, 1913, admission about his “unconscious” bathroom visit to the metal room — the scene of the crime.

Oney, Steve. “The Leo Frank Case Isn’t Dead.” LA Times, October 30, 2009. The class warfare behind the story of his 1915 lynching keeps it tragically relevant. Steve Oney, author of “And the Dead Shall Rise,” is chief consultant to “The People v. Leo Frank.” http://articles.latimes.com/2009/oct/30/opinion/oe-oney30

Oney, Steve. “Murder Trials and Media Sensationalism.” Nieman Reports, Spring 2004.The press frenzy of a century ago echoes in the coverage of trials today, http://www.nieman.harvard.edu/reports/article/100884/Murder-Trials-and-Media-Sensationalism.aspx.

Freeman, Scott. “The Truth At Last.” Atlanta Magazine, October 2003, page 98. Article about Steve Oney and his book, And the Dead Shall Rise (2003), http://books.google.com/books?id=FdECAAAAMBAJ&printsec=frontcover&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false.

__________________________________________

Who Killed Mary Phagan?

By Warren Goldstein

Published: October 26, 2003

AND THE DEAD SHALL RISE

The Murder of Mary Phagan

and the Lynching of Leo Frank.

By Steve Oney.

Illustrated. 742 pp. New York:

Pantheon Books. $35.

THE single most famous lynching in American history remains that of Leo Frank, a Jewish factory superintendent in Atlanta, convicted in 1913 of murdering Mary Phagan, a 13-year-old girl in his employ. Despite national publicity on his behalf, a lynch mob killed Frank two years later. The case made and broke careers, sparked both the Anti-Defamation League and the resurgent Ku Klux Klan, and fanned Southern anti-Semitism and Jewish racism. ”And the Dead Shall Rise,” Steve Oney’s overlong, occasionally dramatic (and melodramatic), exceptionally detailed first book, recounting the trial and its aftermath, helps us appreciate the enduring fascination of this case.

Raised in Brooklyn, Leo Frank earned a degree in mechanical engineering from Cornell and moved South to manage his uncle’s pencil factory. He soon married into Atlanta’s prosperous, apparently assimilated German Jewish community.

While local boosters touted Atlanta as a gleaming modern metropolis, the city’s industrial, commercial and financial elite drew its wealth from the factories employing masses of poorly paid, badly housed, overworked, malnourished migrants from the countryside. Little of the New Southern prosperity trickled down to Atlanta’s children, many of whom, like Mary Phagan, started factory work at the age of 10.

On April 27, 1913, a night watchman discovered her beaten, contorted body in the filthy factory basement. Mary had been strangled, possibly raped, her face ground in the dirt. Detectives soon arrested Frank, mainly because he was the last person to acknowledge seeing her alive. The murder crystallized working-class Atlantans’ resentment over their children’s exploitation by heartless capitalists. Police and prosecutors leaked ”evidence” that Frank habitually harassed his female employees. That Mary had apparently been garroted by a libidinous Yankee Jew stoked passions throughout the city, and provided grist for all three competing sensationalist newspapers.

Seventeen years in the making, ”And the Dead Shall Rise” provides a feint-by-feint, blow-by-blow account of pretrial, trial and post-trial maneuvering and publicity. Most readers might have appreciated Oney’s own overview of — and judgments about — the often bewildering morass of multiplying, contradictory testimony and evidence. Much of the trial evidence against Frank was circumstantial, and some testimony very likely was coerced. Most damning of all was the confession — actually, three successive affidavits, each more detailed and produced under police interrogation — of a black sweeper at the factory, Jim Conley, who claimed to have assisted Frank in disposing of the girl’s body. Despite his many arrests for drunk and disorderly conduct, and two stretches on a chain gang, Conley proved surprisingly unshakable on the witness stand.

How did the testimony of a decidedly unrespectable black janitor stand up against that of an educated, articulate white man whose lawyer played the race card shamelessly in his summation, arguing, ”Negroes rob and ravish every day in the most peculiar and shocking way?”

Too absorbed in his narrative, Oney does not provide the wider context that answers the question. As the historian Leonard Dinnerstein points out in ”The Leo Frank Case” (1968), the arrival of millions of Russian and Polish Jews in the 1890’s had given rise to a nationwide intensification of anti-Semitic actions, articles and pronouncements, including a federal government report that accused Jews of being heavily involved in the white slave trade. Lurid rumors about rapacious Jews — fueled by the prosecution’s suggestion that Frank was a sodomite who killed Mary when she resisted him — circulated throughout Atlanta, and anti-Frank crowds surrounded the courthouse daily. In this hothouse atmosphere the jury deliberated less than two hours before finding Frank guilty; the next day the judge sentenced him to death.

Organized Jewry intervened, financially and otherwise. Adolph Ochs, publisher of The New York Times, and Louis Marshall, president of the American Jewish Committee, threw their institutions behind Frank. Between The Times’s sympathetic coverage and Marshall’s money, contacts and legal expertise, the case became a national cause célèbre. When the Supreme Court denied Frank’s request for a new trial, two million signed petitions and 100,000 people sent letters asking Georgia’s popular, progressive governor, John Slaton, to commute Frank’s death sentence to life imprisonment.