by Elliot Dashfield

A review of The Leo Frank Case by Leonard Dinnerstein, University of Georgia Press

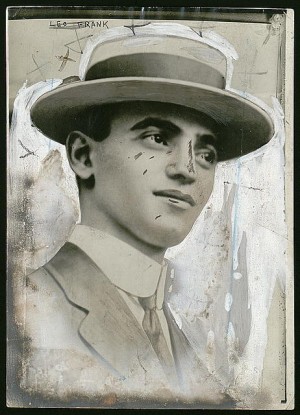

IN 1963, nearly a half century after the sensational trial and lynching of Leo Frank become a national cause célèbre, a graduate student named Leonard Dinnerstein (pictured) decided to make the Frank case the subject of his PhD thesis. Three years later, Dinnerstein submitted his dissertation to the political science department of Columbia University — and his thesis became the basis of his 1968 book, The Leo Frank Case. Dinnerstein’s book has undergone numerous tweaks, additions, and revisions over the years – more than a half dozen editions have been published. His latest version, published in 2008, is the culmination of his nearly 50 years of research into the Leo Frank affair.

Readability: two out of five stars

Dinnerstein lacks eloquence. He produces flat, cardboard-colored “social history.” The language is stale, bland, and dated. If it weren’t for the fascinating topic, the book would be an intolerable and impossible-to-finish bore. I do wonder how many readers pick up this book and never finish it.

Honesty, Integrity and Reliability: one out of five stars

Given the many decades Leonard Dinnerstein has spent studying the Leo Frank case, and assuming Dinnerstein is a scholar, I find it almost impossible to understand the sheer number of conspicuous errors, misquotes, fabrications, misrepresentations, and shameless omissions made in every edition of this book from 1968 to 2008.

Examining Dinnerstein’s 1966 PhD dissertation, I discovered the probable explanation. Dinnerstein’s central thesis – and his motivation for a half century of work – is his belief that “widespread anti-Semitism” in the South was the reason Leo Frank was indicted and convicted. Dinnerstein takes this as his position – and makes it his mission to convince us of its truth – despite the consensus, among Jewish and Gentile historians alike, that anti-Semitism was virtually unknown in the South, and despite the fact every level of the United States legal system from 1913 to 1986 let stand the verdict of the 1913 Leo Frank jury trial that unanimously convicted Leo Frank of murder – and despite the fact that the Fulton County Grand Jury that unanimously indicted Leo Frank had three Jewish members.

The question that naturally arises in the mind of any unbiased reader is: What compelled these men to vote unanimously to indict and convict Frank, and what compelled our leading jurists to let his conviction stand after the most intensely argued and well researched appeals? Was it the facts, testimony, and evidence presented to them? Or was it anti-Semitism?

Was the Georgia Supreme Court anti-Semitic when it stated affirmatively that the evidence presented at the Leo Frank trial sustained his conviction? Was the United States Supreme Court anti-Semitic when its decision went against Leo Frank?

The answer can be found in the official unabridged Leo Frank Trial Brief of Evidence, 1913 – a legal record which Leonard Dinnerstein went to great lengths to obfuscate and distort. And Dinnerstein did not even bother telling the reader what the Georgia Supreme Court records revealed about how Leo Frank’s legal defense fund was utilized.

This is what makes every edition of Dinnerstein’s The Leo Frank Case so disappointing: In order to maintain his position of “anti-Semitism was behind it all,” he had to omit or misrepresent the most relevant facts, evidence, and testimony from the trial.

Dinnerstein’s myopic view of Jewish-Gentile relations first revealed itself in his 1966 PhD thesis. Ironically, his lack of objectivity itself seemed to propel him upward in the politically-charged worlds of academia and the mass media. That Leo Frank was innocent – and that Southern, white, anti-Semitic haters were exclusively to blame for his conviction – fit the narrative that the leaders in these fields had internalized and wished to propagate as “history.” Dinnerstein’s book was perfect for its intended market – the new intelligentsia that has come to dominate the academy. His book was also seminal in shaping the popular perception of the Leo Frank case. It helped to transform a well-documented true crime case into a semi-fictionalized myth of a stoic Jewish martyr who was framed by a vast anti-Semitic conspiracy.

Leonard Dinnerstein vs. Every Level of the United States System of Justice

Leonard Dinnerstein writes in his 2008 preface, “I have no doubts: Frank was innocent.” This statement, which sets the dominant tone of his book, goes against the majority decisions of every single level of the United States legal system. More than a dozen experienced judges – incomparably more qualified than Dinnerstein to sift the evidence – reviewed the evidence and arguments put forth by Frank’s own legal team, along with the Leo Frank trial testimony, affidavits, facts, and law pertaining to the case – and all came to the same conclusion: They sustained the guilty verdict of the jury.

If a person was subpoenaed to testify at a criminal trial involving a 29-year-old man accused of bludgeoning, raping, and strangling a 13-year-old girl, and this witness knowingly falsified and withheld evidence about the defendant – that’s called perjury. If the witness provided perjured testimony and this was later proven beyond a reasonable doubt by a trial jury, that witness would likely find himself in prison for a number of years. But when an academic spends 40 years of his life muddling facts, withholding evidence, fraudulently manipulating the official legal records and testimony of a real criminal case, we call him not perjurer, but “historian.”

I have read nearly everything written by Leonard Dinnerstein – not just his books, but his numerous magazine and journal articles. I purchased every edition of Leonard Dinnerstein’s books. I took the time to read, cross reference, and compare his works against the sources he cites in his bibliographies. The only conclusion I am able to come to is that Leonard Dinnerstein shows an unrelenting pattern of inventing facts, misquoting, dramatizing, befogging, embellishing, overstating, and oversimplifying incidents in his books. Dinnerstein’s books – supposedly non-fiction – are filled with a fairly skillful, though flat and boring, simulation of academic analysis and research. They can be, and are indeed designed to be, persuasive to those who don’t bother to read the original sources or do any fact-checking.

For those who have carefully studied the three major Atlanta dailies (Georgian, Constitution and Journal) through the years 1913 to 1915, learning about the Leo Frank case through their day-by-day accounts – and then cross-referencing them with the official legal records of the Leo Frank trial and appeals – Leonard Dinnerstein’s book is a colossal letdown, a failure, and a disgrace.

Evidence of Dishonesty

In his article in the American Jewish Archive Journal (1968) Volume 20, Number 2, Dinnerstein makes his now-famous claim that mobs of anti-Semitic Southerners, outside the courtroom where Frank was on trial, were shouting into the open windows “Crack the Jew’s neck!” and “Lynch him!” and that members of the crowd were making open death threats against the jury, saying that the jurors would be lynched if they didn’t vote to hang “the damn sheeny.”

But not one of the three major Atlanta newspapers, who had teams of journalists documenting feint-by-feint all the events in the courtroom, large and small, and who also had teams of reporters with the crowds outside, ever reported these alleged vociferous death threats. And certainly such a newsworthy event could not be ignored by highly competitive newsmen eager to sell papers and advance their careers. Do you actually believe that the reporters who gave us such meticulously detailed accounts of this Trial of the Century, even writing about the seating arrangements in the courtroom, the songs sung outside the building by folk singers. and the changeover of court stenographers in relays, would leave out all mention or notice of a murderous mob making death threats to the jury? During the two years of Leo Frank’s appeals, none of these alleged anti-Semitic death threats were ever reported by Frank’s own defense team. There is not a word of them in the 3,000 pages of official Leo Frank trial and appeal records – and all this despite the fact that Reuben Arnold made the claim during his closing arguments that Leo Frank was tried only because he was a Jew.

The patently false accusation that European-American Southerners used death threats to terrorize the jury into convicting Leo Frank is a racist blood libel, pure and simple. Yet, thanks to Leonard Dinnerstein, this fictional episode has entered the consciousness of Americans of all stations as “history” – as one of the pivotal facts of the Frank case. It has been repeated countless times, in popular articles and academic essays, on stage and on film and television, and, as the 100th anniversary of the case approaches, it will be repeated as many times again – until there is not a single man, woman, or child who is unaware of it. That is anti-history, not history. I would say shame on Leonard Dinnerstein – if I thought him a being capable of shame.

Dinnerstein, who supported himself almost his entire life by writing about anti-Semitism, would surely know better than anyone else that if such an incident had actually happened, it would have been the stuff of lurid headlines long before 1918, to say nothing of 1968. His contempt for us – his firm belief that we will not check any of his claims – is palpable.

More Deception

Leonard Dinnerstein was interviewed for the video documentary The People vs. Leo Frank (2009). In that interview, he makes statements that he must know to be untrue about the death notes found on Mary Phagan’s body.

The documentary shows us a dramatization of the interrogation of Jim Conley by the Atlanta Police in May, 1913 – and Dinnerstein then states:

“They [the Atlanta police] asked him [Jim Conley] about the notes. He said ‘I can’t read and write.’ That happened to come up in a conversation between the police and Frank, and Frank said, ‘Of course he can write; I know he can write, he used to borrow money from me and sign promissory notes.’ So Conley had not been completely honest with the police.” (The People vs. Leo Frank, 2009).

This Dinnerstein segment has been posted on YouTube and the documentary is commercially available. Notice that Dinnerstein’s clear implication is that Leo Frank blew the whistle on Jim Conley’s false claim of being illiterate, and that Frank was the instrument of this discovery. But that is a bald-faced lie.

Leo Frank was arrested on April 29, 1913 and Jim Conley was arrested two days later, on May 1. Leo Frank never admitted to the police that he knew Jim Conley could write until weeks after that fact was already known to investigators. Pinkerton detective Harry Scott was informed that Jim Conley could write by an operative who spoke to a pawnbroker – not by Leo Frank. On May 18, 1913, after two and a half weeks of interrogation, Atlanta police finally got Conley to admit he wrote the Mary Phagan death notes — but Conley revealed he did so at the behest of Leo Frank. After several successive interrogations, the approximate chain of events became clear.

Leo Frank kept completely quiet about the fact that Jim Conley could read and write for more than two weeks, even though Jim Conley – working as a roustabout at the factory – had done written inventory work for Frank. Leo Frank also allowed Jim Conley to run a side business out of the National Pencil Company, wheeling and dealing pocket watches under questionable circumstances. In one of these deals, Conley was said to have defrauded Mr. Arthur Pride, who testified about it at the Leo Frank trial. Frank himself vetted and managed Conley’s pocket watch contracts, keeping them locked in his office safe. Leo Frank would take out small payments from Conley’s weekly wages and pay down the pawnshop owner’s loans. Leo Frank didn’t tell investigators he was overseeing Conley’s watch contracts until it was far too late, after the police had found out about it independently.

I encourage people to read the official Leo Frank trial Brief of Evidence, 1913, to see for themselves whether or not Leo Frank informed the police about Jim Conley’s literacy immediately after he was arrested – or if he only admitted to that fact after the police had found out about it through other means weeks later. This is something that Leonard Dinnerstein, familiar as he has been – for decades – with the primary sources in the case, must have known for a very long time. Yet in this very recent interview, he tries to make us believe the precise opposite of the truth – tries to make us believe that Frank was the one who exposed this important fact. There’s a word for what Dinnerstein is, and it’s not “historian.”

One of the Biggest Frauds in the Case

Dinnerstein knowingly references claims that do not stand up to even minimal scrutiny. For example, he uncritically accepts the 1964 hoax by hack writer and self-promoter Pierre van Paassen, who claimed that there were in existence in 1922 X-ray photographs at the Fulton County Courthouse, taken in 1913, of Leo Frank’s teeth, and also X-ray photographs of bite marks on Mary Phagan’s neck and shoulder – and that anti-Semites had suppressed this evidence.. Van Paassen further alleged – and Dinnerstein repeated – that the dimensions of Frank’s teeth did not match the “bite marks,” thereby exonerating Frank.

Here’s the excerpt from van Paassen’s 1964 book To Number Our Days (pages 237 and 238) that Dinnerstein endorses:

“The Jewish community of Atlanta at that time seemed to live under a cloud. Several years previously one of its members, Leo Frank, had been lynched as he was being transferred from the Fulton Tower Prison in Atlanta to Milledgeville for trial on a charge of having raped and murdered a little girl in his warehouse which stood right opposite the Constitution building. Many Jewish citizens who recalled the lynching were unanimous in assuring me that Frank was innocent of the crime.

“I took to reading all the evidence pro and con in the record department at the courthouse. Before long I came upon an envelope containing a sheaf of papers and a number of X-ray photographs showing teeth indentures. The murdered girl had been bitten on the left shoulder and neck before being strangled. But the X-ray photos of the teeth marks on her body did not correspond with Leo Frank’s set of teeth of which several photos were included. If those photos had been published at the time of the murder, as they should have been, the lynching would probably not have taken place.

“Though, as I said, the man died several years before, it was not too late, I thought, to rehabilitate his memory and perhaps restore the good name of his family. I showed Clark Howell the evidence establishing Frank’s innocence and asked permission to run a series of articles dealing with the case and especially with the evidence just uncovered. Mr. Howell immediately concurred, but the most prominent Jewish lawyer in the city, Mr. Harry Alexander, whom I consulted with a view to have him present the evidence to the grand jury, demurred. He said Frank had not even been tried. Hence no new trial could be requested. Moreover, the Jewish community in its entirety still felt nervous about the incident. If I wrote the articles old resentments might be stirred up and, who knows, some of the unknown lynchers might recognize themselves as participants in my description of the lynching. It was better, Mr. Alexander thought, to leave sleeping lions alone. Some local rabbis were drawn into the discussion and they actually pleaded with Clark Howell to stop me from reviving interest in the Frank case as this was bound to have evil repercussions on the Jewish community.

“That someone had blabbed out of school became quite evident when I received a printed warning saying: ‘Lay off the Frank case if you want to keep healthy.’ The unsigned warning was reinforced one night or, rather, early one morning when I was driving home. A large automobile drove up alongside of me and forced me into the track of a fast-moving streetcar coming from the opposite direction. My car was demolished, but I escaped without a scratch….”

Dinnerstein references these pages in his book (page 158 of the 2008 edition), saying “In 1923, at the height of the Ku Klux Klan’s power, a foreign journalist, working for The Atlanta Constitution, became interested in Leo Frank and went back to study the records of the case. He came across some x-rays showing teeth indentations in Mary Phagan’s left shoulder and compared them with x-rays of Frank’s teeth; but the two sets did not correspond. On the basis of this, and other insights garnered from his investigation, the newspaperman wanted to write a series ‘proving’ Frank’s innocence. One anonymous correspondent sent him a printed note: ‘Lay off the Frank case if you want to keep healthy,’ but this did not deter him.”

Since Dinnerstein is such a lofty academic scholar and professor, perhaps he simply forgot to ask a current freshman in medical school if it was even possible to X-ray bite marks on skin in 1913 – or necessary in 2012, for that matter – because it’s not. In 1913, X-ray technology was in its infancy and never used in any criminal case until many years after Leo Frank was hanged. Was Leo Frank’s lawyer named “Harry Alexander” or Henry Alexander? Why would the famous attorney who represented Leo Frank during his most high-profile appeals say he didn’t have his trial yet?! Leo Frank was not lynched on his way to trial in Milledgeville – he wasn’t on his way to anywhere, and it happened in Marietta, 170 miles away. And it defies the laws of physics, and all logic and reason, to believe that any person driving a motor vehicle in 1922 – when there were virtually no safety features in automobiles – could suffer a direct collision with a “fast-moving streetcar” and survive “without a scratch.” Oddly, Dinnerstein says van Paassen “was not deterred” from writing the supposed series of articles, though even the hoaxer himself clearly implies that he was indeed deterred. (Even the most basic online research would also have shown that van Paassen is a far from credible source who once publicly claimed to have seen supernatural “ghost dogs” which could appear and disappear at will.)

Not only did Dinnerstein completely fail to point out the obviously preposterous nature of van Paassen’s account, but he blandly presents his claims as established historical fact. If this is scholarship, then Anton LaVey is the Pope.

Surely Leonard Dinnerstein has had, and continues to have, access to the primary sources in this case. Certainly he can read the official legal documents online at the State of Georgia’s online archive known as the Virtual Vault, as I have done without difficulty.

It is hard to fathom the deep contempt that Leonard Dinnerstein must have for his readers. Did he think that these official legal records, once buried in dusty government vaults, would never make their way online? Did he think that Georgia’s three major newspapers from 1913 to 1915, the Atlanta Constitution, Atlanta Journal, and Atlanta Georgian, would never make their way online? Or does his contempt run even deeper – did he think that, online or not, none of us would ever check up on his claims?

Covering Up the Racial Strategy of the Defense

What one can most charitably call Leonard Dinnerstein’s lack of candor is apparent not only in sins of commission, but also of omission. In his book, Dinnerstein completely fails to mention the well-known strategy of Leo Frank’s defense team to play on the racial conflicts present in 1913 Georgia and pin the murder of Mary Phagan on, successively, two different African-American men.

The first victim was Newt Lee, the National Pencil Company’s night watchman. After that intrigue fell apart, Frank’s team abruptly changed course and tried to implicate the firm’s janitor – and, according to his own testimony, Frank’s accomplice-after-the-fact – James “Jim” Conley. Leo Frank’s defense team played every white racist card they could muster against Jim Conley at the trial, and continued doing so through two years of appeals. Frank’s own lawyer, addressing the jury, said “Who is Conley? Who was Conley as he used to be and as you have seen him? He was a dirty, filthy, black, drunken, lying nigger…Who was it that made this dirty nigger come up here looking so slick? Why didn’t they let you see him as he was?” Had this been said at trial by anyone other than Leo Frank’s defense attorney, it would have been thoroughly denounced by any academic with even half the normal quota of flaming outrage against white racism. But as for Dinnerstein…. Well, with only 40 years to study the case, I suppose he just overlooked it.

A Mockery

Leonard Dinnerstein’s The Leo Frank Case is a mockery of legal history. Dinnerstein intentionally leaves out volumes of damaging evidence, testimony, and facts about the case. His glaring omissions are documented in, among many other sources, the Georgia Supreme Court’s Leo Frank case file. Leonard Dinnerstein misleads the reader, rewriting the case almost at will, and incorporating long-discredited and nonsensical half-truths that would never stand up to even the most elementary scrutiny.

Dinnerstein has created a book that will be remembered by history as a shameless, over-the-top attempt to create a mythology of Leo Frank as a “martyr to anti-Semitism.” In doing that, he seems to care not at all that he may be rehabilitating the image of a serial pedophile, rapist, and strangler. To Dinnerstein, the fact that Leo Frank is Jewish, and his belief that Southern whites were anti-Jewish, are all-important realities – far more important than the facts of the case, which he presents very selectively to persuade us that his ethnocentric view is the only correct one. Leonard Dinnerstein’s partisanship borders on the pathological, and his integrity is, like Pierre van Paassen’s, essentially nonexistent.

The definitive, comprehensive, objective book on the Leo Frank case has, unfortunately, never been written. But as an antidote to Dinnerstein’s myth-making, you might want to read The Murder of Little Mary Phagan by Mary Phagan Kean. Although her book is amateurishly written, she did make a refreshingly honest effort to present both sides of the case in an unbiased manner.

This doesn’t mean I haven’t found errors in Kean’s book – I have – but compared to all the major Leo Frank authors (Oney, Dinnerstein, Alphin, Melnick, the Freys, and Golden) who have written about the case in the last 99 years, Mary Phagan Kean made the best and most honest attempt to be fair, balanced, and neutral, despite her belief in Leo Frank’s guilt. The same cannot be said for Leonard Dinnerstein.

I have closely studied the several thousand pages of the Leo Frank trial and appeal records (1913 – 1915), read every book (1913 – 2010) on the subject, and reviewed, more than once, the three primary Atlanta newspapers, the Journal, Constitution, and Georgian (1913 – 1915), concerning their coverage of the Leo Frank case. I believe the jury made the correct decision in the summer of 1913.

But regardless of my opinion on any matter, with which reasonable men and women may well disagree, there is no doubt whatever that the accusations of anti-Jewish shenanigans, threats, and jury intimidation at the Leo Frank trial, promoted by Leonard Dinnerstein and repeated by many others, are flat-out lies. His creation and perpetuation of such tales amounts to perjury. And his is an especially vile kind of perjury, made by one who is pathologically obsessed with anti-Semitism and who imagines persecution where none exists. His is a perjury that creates injustice not just for one victim and one perpetrator, but, by twisting and distorting our view of the past, for our entire society.

___

REFERENCES:

Leonard Dinnerstein’s original dissertation

To Number Our Days by Pierre van Paassen

Read the original article at The American Mercury