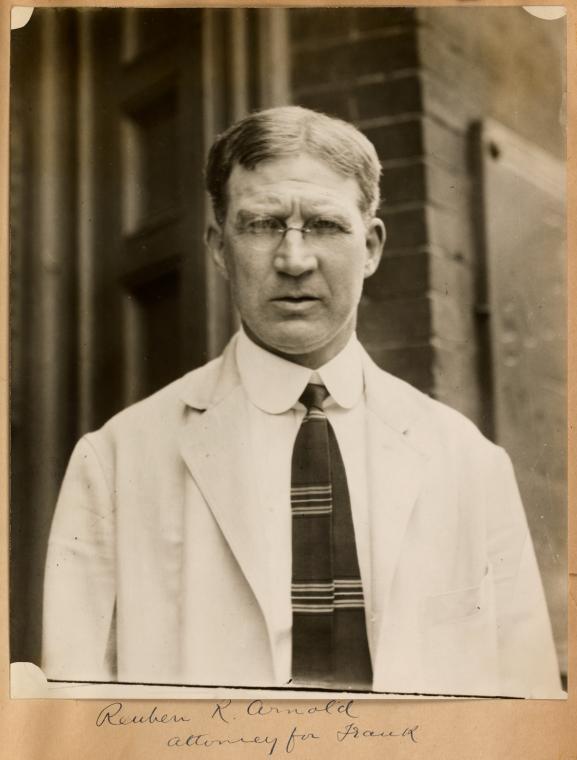

There were two major speeches that Reuben Rose Arnold made on behalf of Leo Frank in 1913 that survived the last century and are available to this date, the first was his closing argument speech given at the end of the Leo M. Frank criminal trial in late August 1913, it is captured in Lawson’s American State Trials Volume X 1918 (which is available online in the Leo Frank bibliography) and the second was the Argument of Reuben Rose Arnold given at a hearing in October 1913 after the murder trial for the purpose of attemping to have the verdict set aside and a new trial issued.

Reuben R. Arnold’s August 1913 and October 1913 speeches are often Confused Even Amongst Prominent Leo Frank Authors

A common mix-up with the 1914 published booklet “Argument of Reuben Rose Arnold” originally delivered to the court in October 1913 is the title is too often mistaken for and confused with the final closing argument and statement Reuben Rose Arnold gave at the end of the criminal trial of Leo M. Frank in late August 1913.

In the October 1913 speech, Reuben Arnold speaks alone this time in an attempt, to have the verdict of guilt rendered against Leo Frank set aside and get new trial issued for Leo Frank by the trial Judge Leonard S. Roan. This attempt failed and was the first step of 2 years of appeals.

Reuben Arnold’s October 1913 speech tends to be a more emotionally compelling speech than his August 1913 closing argument. Leo Frank detractors perceived Arnold’s October speech as desperate and hollow.

Available in PDF Format:

The October 1913, Argument of Reuben Rose Arnold after the Trial of Leo M. Frank. The post-Trial speech on behalf of Leo Frank, Reuben R. Arnold’s Address to the Court on his Behalf in October 1913. Introduction by Alvin V. Sellers. Classic Publishing Co., Baxley GA. Copyright, 1915 by Alvin V. Sellers and The Trow Press, New York. Booklet format, 69 pages and published in 1915. Original booklets are extremely rare and difficult to find in superior condition. Scanned and brought to you by the Leo Frank Research Archive LeoFrank.org. Available here in Adobe PDF. A review of the Final Trial Statement concerning the Leo Frank Trial by Reuben Rose Arnold, October 1913 can be found on Internet Archive www.archive.org.

Compare the Two Speeches of Reuben Rose Arnold on Behalf of Leo Frank

We recommend you read the PDF version of the Argument of Reuben Arnold (October 1913) and the closing argument (August 1913) of Reuben Arnold at the Leo M. Frank murder trial (available in Lawson’s American State Trials Volumne X 1918) to compare the two.

We have provided the text versions of the late August 1913 final closing arguments of the Leo Frank criminal trial published below, and then after that the October 1913 Argument of Reuben Rose Arnold at the re-trial request hearing, both speeches are also available in PDF format above and in OCR Text Format below:

August 1913 Speech at the Leo Frank Trial Below, thereafter Oct 1913 speech at the hearing to get Leo Frank a new trial (read both and compare)

AUGUST 1913 MR. ARNOLD, FOR THE PRISONER.

Mr. Arnold. Gentlemen of the Jury: We are all to be

congratulated that this case is drawing to a close. We have

all suffered here from trying a long and complicated case at

the heated term of the year. It has been a case that has

taken so much effort and so much concentration and so much

time, and the quarters here are so poor, that it has been par-

ticularly hard on you members of the jury who are prac-

tically in custody while the case is going on. I know it’s

hard on a jury, to be kept confined this way, but it is neces-

sary that they be segregated and set apart where they will

get no impression at home nor on the street. The members of

the jury are in a sense set apart on a mountain, where, far

removed from the passion and heat of the plain, calmness

rules them and they can judge a case on its merits.

My friend Hooper said a funny thing here a while ago.

I don’t think he meant what he said, however. Mr. Hooper

said that the men in the jury box are not different from the

men on the street. Your Honor, I’m learning something

every day, and I certainly learned something today, if that’s

true.

Mr. Hooper: Mr. Arnold evidently mistakes my meaning, which

I thought I made clear. I stated that the men in the jury box were

like they would be on the street in the fact that in making up their

minds about the guilt or innocence of the accused they must use the

same common sense that they would if they were not part of the

court.

263 X. AMERICA” STATE TRIALS.

[Mr. Arnold next described the horrible crime that had

been committed that afternoon or night in the National Pencil

Company’s dark basement. He dwelt on the effect of the

crime upon the people of Atlanta and of how high feeling

ran and still runs, and of the omnipresent desire for the

death of the man who committed the crime.]

There are fellows like that street car man, Kendley, the one

who vilified this defendant here and cried for him to be

lynched, and shouted that he was guilty until he made him-

self a nuisance on the cars he ran. Why, I can hardly realize

that a man holding a position as responsible as that of a mo-

torman and a man – with certain police powers and the discre-

tion necessary to guide a car through the crowded city streets

would give way to passion and prejudice like that. It was

a type of man like Kendley who said he did not know for sure

whether those negroes hanged in Decatur for the shooting of

the street car men were guilty, but he was glad they were

hung, as some negroes ought to be hanged for the crime. He’s

the same sort of a man who believes that there ought to be

a hanging because that innocent little girl was murdered,

and who would like to see this Jew here hang because some-

body ought to hang for it.

I’ll tell you right now, if Frank hadn’t been a Jew there

would never have been any prosecution against him. I’m

asking my own people to turn him loose, asking them to do

justice to a Jew, and I’m not a Jew, but I would rather die

before doing injustice to a Jew.

This case has just been built up by degrees; they have a

monstrous perjurer here in the form of this Jim Conley

against Frank. You know what sort of a man Conley is, and

you know that up to the time the murder was committed no

one ever heard a word against Frank. Villainy like this

charged to him does not crop out in a day. There are long

mutterings of it for years before. There are only a few who

have ever said anything against Frank. I want to call your

attention later to the class of their witnesses and the class of

ours. A few floaters around the factory, out of the hundreds

264 LEO M. FRANK. 265

who have worked there in the plant three or four years, have

been induced to come up here and swear that Frank has not

a good character, but the decent employees down there have

sworn to his good character. Look at the jail birds they

brought up here, the very dregs of humanity, men and

women – who have disgraced themselves and who now have

come and tried to swear away the life of an innocent man.

I know that you members of the jury are impartial. That’s

the only reason why you are here, and I’m going to strip the

state’s case bare for you, if I have the strength to last to do

it. They have got to show Frank guilty of one thing before

you can convict him; they’ve got to show that he is guilty

of the murder, no matter what else they show about him.

You are trying him solely for the murder, and there must be

no chance that anyone else could just as likely be guilty. If

the jury sees that there is just as good a chance that Conley

can be guilty, then they must turn Frank loose

Now, you can see how in this case the detectives were put

to it to lay the crime on somebody. First, it was Lee, and

then it was Gantt, and various people came in and declared

they had seen the girl alive late Saturday night and at other

times, and no one knew what to do. Well, suspicion turned

away from Gantt, and in a little while it turned away from

Lee.

Now, I don’t believe that Lee is guilty of the crime,

but I do believe that he knows a lot more about the crime

than he told. He knows about those letters and he found

that body a lot sooner than he said he did.

Oh, well, the whole case is a mystery, a deep mystery, but

there is one thing pretty plain, and that is that whoever wrote

those notes committed the crime. Those notes certainly had

some connection with the murder, and whoever wrote those

notes committed the crime.

Well, they put Newt Lee through the third degree and the

fourth degree, and maybe a few others. That’s the way, you

know, they got this affidavit from the poor negro woman,

Minola MecKnight. Why, just the other day the supreme

court handed down a decision in which it referred to the third

X. AMERICAN STATE TRIALS.

degree methods of the police and detectives in words that

burned.

Well, they used those methods with Jim Conley. My

friend, Hooper, said nothing held Conley to the witness chair

here but the truth, but I tell you that the fear of a broken

neck held him there. I think this decision about the third

degree was handed down with Conley’s case in mind. I’m

going to show this Conley business up before I get through.

I’m going to show that this entire case is the greatest frame-

up in the history of the state.

My friend Hooper remarked something about circumstan-

tial evidence, and how powerful it frequently was. He forgot

to say that the circumstances, in every case, must invariably

be proved by witnesses. History contains a long record of

circumstantial evidence, and I once had a book on the sub-

ject which dwelt on such cases, most all of which sickens the

man who reads them. Horrible mistakes have been made by

circumstantial evidence-more so than by any other kind.1

Hooper says, “Suppose Frank didn’t kill the girl, and Jim

Conley did, wasn’t it Frank’s duty to protect her” He was

taking the position that if Jim went back there and killed

her, Frank could not help but know about the murder.

Which position, I think, is quite absurd. Take this hypo-

thesis, then, of Mr. Hooper’s. If Jim saw the girl go up and

went back and killed her, would he have taken the body down

the elevator at that time? Wouldn’t he have waited until

Frank and White and Denham, and Mrs. White and all

others were out of the building? I think so. But there’s not

a possibility of the girl having been killed on the second floor.

Hooper smells a plot, and says Frank has his eye on the little

girl who was killed. The crime isn’t an act of a civilized

1 Here Mr. Arnold cited the Durant case in San Francisco, the

Hampton case in England, and the Dreyfus case in France as in-

stances of mistakes of circumstantial evidence. In the Dreyfus

case he declared it was purely persecution of the Jew. The hide-

ousness of the murder itself was not as savage, he asserted, as the

feeling to convict this man. But the savagery and- venom is there

just the same, and it is a case very much on the order of Dreyfus.

266

man-it’s the crime of a cannibal, a man-eater. Hooper is

hard-pressed and wants to get up a plot-he sees he has to

get up something. He forms his plot from Jim Conley’s

story.

They say that on Friday, Frank knew he was going to

make an attack of some sort on Mary Phagan. The plot

thickens. Of all the wild things I have ever heard, that is the

wildest. It is ridiculous. Mary Phagan worked in the pencil

factory for months, and all the evidence they have produced

that Frank ever associated with her-ever knew her-is the

story of weasley little Willie Turner, who can’t even describe

the little girl who was killed.

A little further on in his story, Jim is beginning the plot.

They used him to corroborate everything as they advised.

Jim is laying the foundation for the plot. What is it-this

plot? Only that on Friday Frank was planning to commit

some kind of assault upon Mary Phagan. Jim was their tool.

Even Scott swears that when he told Jim that Jim’s story

didn’t fit, Jim very obligingly adapted it to suit his defense.

He was scrupulous about things like that. He was quite con-

siderate. Certainly. He had his own neck to save.

Jim undertook to show that Frank had an engagement with

some woman at the pencil factory that Saturday morning.

There is no pretense that another woman is mixed up in the

case. No one would argue that he planned to meet and

assault this innocent little girl who was killed. Who but God

would know whether she was coming for her pay that Friday

afternoon or the next Saturday? Are we stark idiots? Can’t

we divine some things?

They’s got a girl named Ferguson, who says she went for

Mary Phagan’s pay on the Friday before she was killed, and

that Frank wouldn’t give it to her. It is the wildest theory

on earth, and it fits nothing. It is a strained conspiracy.

Frank, to show you I am correct, had nothing whatever to do

with paying off on Friday. Schiff did it all. And little Mag-

nolia Kennedy, Helen Ferguson’s best friend, says she was

with Helen when Helen -went to draw her pay, and that Helen

LEO M. FRANK. 267 – X. AMERICAN STATE TRIALS.

never said a word about Mary’s envelope. There’s your con-

spiracy, with Jim Conley’s story as its foundation. It’s too

thin. It’s preposterous.

Then my friend Hooper says Frank discharged Gantt be-

cause he saw Gantt talking to Mary Phagan. If you con-

vict men on such distorted evidence as this, why you’d be

hanging men perpetually. Gantt, in the first place, doesn’t

come into this case in any good light. It is ridiculously ab-

surd to bring his discharge into this plot of the defense.

Why, even Grace Hicks, who worked with Mary Phagan, and

who is a sister-in-law of Boots Rogers, says that Frank did

not know the little girl.

Hooper also says that bad things are going on in the pen-

cil factory, and that it is natural for men to cast about for

girls in such environments. We are not trying this case on

whether you or I or Frank had been perfect in the past. This

is a case of murder. Let him who is without sin cast the first

stone. I say this much, and that is that there has been as

little evidence of such conditions in this plant as any other

of its kind you can find in the city. They have produced

some, of course, but it is an easy matter to locate some ten

or twelve disgruntled ex-employees who are vengeful enough

to swear against their former superintendent, even though

they don’t know him except by sight.

I want to ask this much: Could Frank have remained at

the head of this concern if he had been as loose morally as

the state has striven to show. If he had carried on with the

girls of the place as my friend alleged, wouldn’t the entire

working force have been demoralized, ruined? He may have

looked into this dressing room, as the little Jackson girl says,

but, if he did, it was done to see that the girls weren’t loiter-

ing. There were no lavatories, no toilets, no baths in these

dressing rooms. The girls only changed their top garments.

He wouldn’t have seen much if he had peered into the place.

You can go to Piedmont park any day and see girls and

women with a whole lot less on their persons. And to the

shows any night you can see the actresses with almost nothing

268 LEO M. FRANK.

on. Everything brought against Frank was some act he did

openly and in broad daylight, and an act against which no

kick was made.

The trouble with Hooper is that he sees a bear in every

bush. He sees a plot in this because Frank told Jim Conley

to come back Saturday morning. The office that day was

filled with persons throughout the day. How could he know

when Mary Phagan was coming or how many persons would

be in the place when she arrived?

This crime is the hideous act of a negro who would ravish

a ten-year-old girl the same as he would ravish a woman of

years. It isn’t a white man’s crime. It’s the crime of a

beast-a low, savage beast!

Now, back to the case. There is an explorer in the pencil

factory by the name of Barrett-I call him Christopher Co-

lumbus Barrett purely for his penchant for finding things.

Mr. Barrett discovered the blood spots in the place where

Chief Beavers, Chief Lanford and Mr. Black and Air. Starnes

had searched on the Sunday of the discovery. They found

nothing of the sort. Barrett discovered the stains after he

had proclaimed to the whole second floor that he was going

to get the $4,000 reward if Mr. Frank was convicted. Now,

you talk about plants! If this doesn’t look mighty funny

that a man expecting a reward would find blood spots in a

place that has been scoured by detectives, I don’t know what

does. Four chips of this flooring were chiseled from this

flooring -where these spots were found. The floor was an inch

deep in dirt and grease. Victims of accidents had passed by

the spot with bleeding fingers and hands. If a drop of blood

had ever fallen there, a chemist could find it four years later.

Their contention is that all the big spots were undiluted blood.

Yet, let’s see how much blood Dr. Claude Smith found on the

chips. Probably five corpuscles, that’s all, and that’s -what

he testified here at the trial. My recollection is that one sin-

gle drop of blood contains 8,000 corpuscles. And, he found

these corpuscles on only one chip. I say that half of the

blood had been on the floor two or three years. The stain on

269 X. AMERICAN STATE TRIALS.

all chips but one were not blood. Dorsey’s own doctors have

put him where he can’t wriggle-his own evidence hampers

him! They found blood spots on a certain spot and then had

Jim adapt his story accordingly. They had him put the find-

ing of the body near the blood spots, and had him drop it

right where the spots were found.

It stands to reason that if a girl had been wounded on the

lathing machine, there would have been blood in the vicinity

of the machine. Yet, there was no blood in that place, and

neither was there any where the body was said to have been

found by Conley. The case doesn’t fit. It’s flimsy. And,

this white machine oil that they’ve raised such a rumpus over.

It was put on the floor as a cheap, common plant, to make it ap-

pear as though someone had put it there in an effort to hide the

blood spots. The two spots of blood and the strands of hair

are the only evidence that the prosecution has that the girl

was killed on the second floor.

Now, about these strands of hair. Barrett, the explorer,

says he found four or five strands on the lathing machine. I

don’t know whether he did or not. They’ve never been pro-

duced. I’ve never seen them. But, it’s probable, for just

beyond the lathing machine, right in the path of a draft that

blows in from the window, is a gas jet used by the girls in

curling and primping their hair. It’s very probable that

strands of hair have been blown from this jet to the lathing

machine.

The detectives say that Frank is a crafty, cunning crimi-

nal, when deep down in their heart of hearts they know good

and well that their case is built against him purely because

he was honest enough to admit having seen her that day.

Had he been a criminal, he never would have told about see-

ing her and would have replaced her envelope in the desk,

saying she had never called for her pay.

I believe that a majority of women are good. The state

jumped on poor Daisy Hopkins. I don’t contend, now, mind

you, that she is a paragon of virtue. But there are men who

were put up by the state who are no better than she. For in-

270 LEO M. FRANK. 271

stance, this Dalton, who says openly that he went into the

basement with Daisy. I don’t believe he ever did, but, in

such a ease, he slipped in: There are some fallen women who

can tell the truth. They have characteristics like all other

types. We put her on the stand to prove Dalton a liar, and

she did it. Now, gentlemen, don’t you think the prosecution

is hard pressed when they put up such a character as Dalton?

They say he has reformed. A man with thievery in his soul

never reforms. Drunkards do, and men with bad habits, but

thieves? No. Would you convict a man like Frank on the

word of a perjurer like Dalton?

Now, I’m coming back to Jim Conley. The whole case cen-

ters around him. Mr. Hooper argues well on that part. At

the outset of the case, the suspicion pointed to Frank merely

because he was the only man in the building. It never

cropped out for weeks that anyone else was on the flrst floor.

The detectives put their efforts on Frank because he admitted

having seen the girl. They have let their zeal run away with

them in this case, and it is tragic. They are proud whenever

they get a prisoner who will tell something. The humbler the

victim the worse is the case. Such evidence comes with the

stamp of untruth on its face.

Jim Conley was telling his story to save his neck, and the

detectives were happy listeners. If there is one thing for

which a negro is capable it is for telling a story in detail.

It is the same with children. Both have vivid imaginations.

And a negro is also the best mimic in the world. He can

imitate anybody. Jim Conley, as he lay in his cell and read

the papers and talked with the detectives, conjured up his

wonderful story, and laid the crime on Frank, because the

detectives had laid it there and were helping him do the

same.

Now, Brother Hooper waves the bloody shirt in our face. It

was found, Monday or Tuesday, in Newt Lee’s house, while

Detectives Black and Scott were giving Cain to poor old man

Newt Lee. I don’t doubt for a minute that they knew it

was out there when they started out after it. I can’t say

X. AMERICAN STATE TRIALS.

they planted it, but it does look suspicious. Don’t ask us

about a planted shirt. Ask Scott and Black.

The first thing that points to Conley’s guilt is his original

denial that he could write. Why did he deny it? Why? I

don’t suppose much was thought of it when Jim said he

couldn’t write, because there are plenty of negroes who are in

the same fix. But later, when they found he could, and

found that his script compared perfectly with the murder

notes, they went right on accusing Frank. Not in criminal

annals was there a better chance to lay at the door of another

man a crime than Jim Conley .had.

You see, there is a reason to all things. The detective de-

partment had many reasons to push the case against Frank.

He was a man of position and culture. They were afraid

that someone, unless they pushed the case to the jumping off

place, would accuse them of trying to shield him. They are

afraid of public and sentiment, and do not want to combat it,

so, in such cases, they invariably follow the line of least

resistance.

[Reading Conley’s statement, Mr. Arnold pointed out the use of

words, which he declared no negro would naturally have used. These

were long words with many syllables in them. They said that Conley

used so much detail in his statements that he could not have been

lying! He then read parts of statements which Conley had repudi-

ated as willful lies and, pointed out the wealth of detail with which

they were filled. And yet they say he couldn’t fabricate so much

detail! Oh, *he is smart! He then read the statement of May 24,

in which Conley admitted writing the notes. In this he shows three

different times at which Conley stated ‘he wrote the notes, these

being early in the morning, at 12:04 and at 3 p. m.]

The statements were not genuinely Conley’s. Take the

word “negro.” The first word that a nigger learns to spell

correctly is negro, and he always takes particular pains to

spell it n-e-g-r-o. He knows how to spell it. Listen to the

statement. He says that at first he spelled the word “ne-

gros,” but that Frank did not want the “s” on it and told

him to rub it out, which he did. Then he says that he wrote

the word over.

Look at the notes. He was treed about those notes, and he

272 LEO M. FRANK.

had to tell a lie and put upon someone the burden of instruct-

ing him to write them. The first statement about them was

a blunt lie-a lie in its incipiency. He said he wrote the

notes on Friday. This was untrue, and unreasonable and

he saw it. Frank could not have known anything of an in-

tended murder on Friday from any viewpoint you might

take, and therefore he could not have made Conley write

them on Friday. Ah, gentlemen of the jury, I tell you these

people had a great find when they got this admission from

Conley! If Conley had stayed over there in the Tower with

Uncle Wheeler Mangum he would have told the truth long

ago. There’s where he should have stayed, with Wheeler

Mangum.

My good friend, Dorsey, is all right. I like him. But he

should not have walked hand in glove with the detectives.

There’s where he went wrong. My good old friend, Charlie

Hill would not have done that. He would have let the nigger

stay in the jail with Uncle Wheeler. I like Dorsey. He sim-

ply made a mistake by joining in the hunt, in becoming a part

of the chase. The solicitor should be little short of as fair as

the judge himself. But he’s young and lacks the experience.

He will probably know better in the future. Dorsey did this:

He went to the judge and got the nigger moved from the jail

to the police station. The judge simply said, “Whatever you

say is all right.”

Now, I’m going to show you how John Black got the state-

ment of Conley changed. I am going to give you a demon-

stration. I have learned some things in this case about get-

ting evidence !

They say that Frank cut Conley loose and he decided to

tell the truth. Conley is a wretch with a long criminal rec-

ord. Gentlemen, how can they expect what he says to be

believed against the statement of Leo M. Frank? They say

Conley can’t lie about detail. Here are four pages, all of

which he himself admits are lies. They are about every

saloon on Peters street, saloons to which he went, his shoot-

ing craps, his buying beer and all the ways in which he spent

273 X. AMERICAN STATE TRIALS.

a morning. There is detail enough, and he admits that they

are lies. Now, in his third statement, that of May 28, he

changes the time of writing the letters from Friday to Satur-

day. Here are two pages of what he said, all of which he

afterwards said were lies. He says that he made the state-

ment that he wrote the notes on Friday in order to divert sus-

picion from his being connected with the murder which hap-

pened on Saturday. He also says that this is his final and

true statement. God only knows how many statements he

will make. He said he made the statement voluntarily and

truthfully without promise of reward, and that he is telling

the truth and the whole truth. He said in his statement that

he never went to the building on Saturday. Yet we know

that he was lurking in the building all the morning on the day

of the murder. We know that he watched every girl that

walked into that building so closely that he could tell you the

spots on their dresses. We know that he was drunk, or had

enough liquor in him to fire his blood.

I know why he wouldn’t admit being in that building on

Saturday. He had guilt on his soul, and he didn’t want it

to be known that he was here on Saturday. That’s why.

When they pinned him down, what did he do? He says

that he was watching for Frank. My God, wasn’t he a watch-

man! He said that he heard Frank and Mary Phagan walk-

ing upstairs, and that he heard Mary Phagan scream, and that

immediately after hearing the scream he let Monteen Stover

into the building.

Why, they even have him saying that he watched for

Frank, when another concern was using the very floor space

in which Frank’s office was located, and you know they

wouldn’t submit to anything like that. Look again! He says

that Mr. Frank said, “Jim, can you write?” What a lie! He

admitted that he had been writing for Frank for two years.

It’s awful to have to argue about a thing like this, gentlemen!

You will remember Hooper said, “How foolish of Conley to

write these notes!” How much more foolish, I say, of Frank

to do it!

274

LEO M. FRANTK.

I don’t think that Newt killed the girl, but I believe he dis-

covered the body some time before he notified the police.

Newt’s a good nigge�.

Scott said that it took Conley six minutes to write a part

of one note. Conley said that he wrote the notes three times.

They say that nigger couldn’t lie. Gentlemen, if there is

any one thing that nigger can do, it is to lie. As my good old

friend, Charlie Hill, would say, “Put him in a hopper and

he’ll drip lye!”

He was trying to prove an alibi for himself when he said

that he was not in the factory on Saturday and told all the

things that he did elsewhere on that day. But we know that

the wretch was lurking in the factory all of Saturday morn-

ing. Further, he swore that while he was in Frank’s office he

heard someone approaching, and Mr. Frank cried out, “Gee!

Here come Corinthia Hall and Emma Clarke!” and that

Frank shut him up in a wardrobe until they left. According

to Conley, they came into the factory between 12 and 1

o’clock, when as a matter of fact, we know that they came be-

tween 11 and 12. And as for his being able to fabricate the

details of his statement-why, he knew every inch of that

building from top to bottom! Hadn’t he been sweeping and

cleaning it for a long time? With this knowledge of the build-

ing, he naturally had no trouble in his pantomime after he

had formed his story. The miserable wretch has Frank hid-

ing him in the wardrobe when Emma Clarke came in after the

murder, when it has been proved that she came there and left

before Mary Phagan ever entered the building on that day.

They saw where they were wrong in that statement, and

they made Conley change it on the stand. They made him

say, “I thought it was them.” They knew that that story

wouldn’t fit.

Do you remember, how eagerly Conley took the papers from

the girls at the factory? And do you remember how for four

or five days the papers were full of the fact that Frank’s

home was in Brooklyn, and that his relatives were reported

to be wealthy? Conley didn’t have to go far to get material

X. AMERICAN STATE TBIALS.

for that statement he put in Frank’s mouth. It so happened,

though, that Frank really did not have rich relatives in

Brooklyn. H~is mother testified that his father was in ill

health, and had but moderate means and that his sister worked

in New York for her living.

Gentlemen, am I living or dreaming, that I have to argue

such points as these? This is what you’ve got to do: You’ve

got to swallow every word that Conley has said-feathers and

all, or you’ve got to believe none of it. How are you going

to pick out of such a pack of lies as these what you will believe

and what you will not? Yet, this is what the prosecution has

based the case upon. If this fails, all fails.

And do you remember about the watch, where Conley said

that Frank asked him, “Why do you want to buy a watch for

your wife? My big, fat wife wanted me to buy her an auto-

mobile, but I wouldn’t do it!” Do you believe that, gentle-

men of the jury*%

I tell you that they have mistreated this poor woman ter-

ribly. They have insinuated that she would not come to the

tower to see Frank-had deserted him. When we know that

she stayed away from the jail at Frank’s own request because

he did not want to submit her to the humiliation of seeing him

locked up and to the vulgar gaze of the morbid and to the

cameras of the newspaper men. The most awful thing in the

whole ease is the way this family has been mistreated! The

way they invaded Frank’s home and manipulated his ser-

vants. I deny that the people who did this are representative

of the 175,000 people of Fulton county! We are a fair peo-

ple, and we are a chivalrous people. Such acts as these are

not in our natures.

Conley next changes the time of the writing of the notes to

Saturday, but denies knowledge of the murder. That, of

course, did not satisfy these gentlemen, and they went back

to him. They knew he was dodging incrimination. So they

had him to change the statement again. Scott and other de-

tectives spent six hours at the time with Conley on occasions,

276

LEO M. FRANK.

and used profanity and worried him to get a confession.

Hooper thinks that we have to break down Conley’s testimony

on the stand, but there is no such ruling. You can’t tell when

to believe him, he has lied so much. Scott says the detectives

went over the testimony with Dorsey. There is where my

friend got into it. They grilled Conley for six hours, trying

to impress on him the fact that Frank would not have written

the notes on Friday. They wanted another statement. He

insisted that he had no other statement to make, but he did

change the time of the writing of the notes from Friday to

Saturday. This shows, gentlemen, as clearly as anything can

show, how they got Conley’s statements. In the statement of

May 29, they had nothing from Jim Conley about his knowl-

edge of the killing of the little girl, and the negro merely said

that Frank had told him something about the girl having

received a fall and about his helping Frank to hide the body.

Oh, Conley, we ire going to have you tell enough to have

you convict Frank and yet keep yourself clear. That’s a

smart negro, that Conley. And you notice how the state

bragged on him because he stood up under the cross-examina-

tion of Colonel Rosser. Well, that negro’s been well versed in

law. Scott and Black and Starnes drilled him; they gave him

the broad hints.

We came here to go to trial, and knew nothing of the

negro’s claim to seeing the cord around the little girl’s neck,

or of his claim of seeing Lemmie Quinn go into the factory,

or of a score of other things. Yet, Conley was then telling the

truth, he said, and he had thrown Frank aside. Oh, he was no

longer shielding Frank, and yet he didn’t tell it all when he

said he was telling the whole truth. Well, Conley had a reve-

lation, you know. My friend Dorsey visited with him seven

times. And my friend, Jim Starnes, and my Irish friend,

Patrick Campbell, they visited him, and on each visit Conley

saw new light. Well, I guess they showed him things and

other things. Does Jim tell a thing because it’s the truth,

gentlemen of the jury, or because it fits into something that

another witness has told I Scott says they told him things

277

278 X. AMERICAN STATE TRIALS.

that fitted. And Conley changed things every time he had

a visit from Dorsey and the detectives. Are you going to

hang a man on that? Gentlemen, it’s foolish for me to have

to argue such a thing.

The man that wrote those murder notes is the man who

killed that girl. Prove that man was there and that he wrote

the notes and .you know who killed the girl. Well, Conley

acknowledges he wrote the notes and witnesses have proved

he was there and he admits that, too. That negro was in the

building near the elevator shaft; it took but two steps for

him to grab that little girl’s mesh bag. She probably held on

to it and struggled with him. A moment later he had struck

her in the eye and she had fallen. It is the work of a moment

for Conley to throw her down the elevator shaft.

Isn’t it more probable that the story I have outlined is true

than the one that Conley tells on Frank? Suppose Conley

were now under indictment and Frank out, how long would

such a story against Frank stand the pressure?

In the statement of May 29 there are any number of things

that are not told of which later were told on the stand. In the

May 29 statement Conley never told of seeing Mary Phagan

enter; he never told of seeing Mfonteen Stover enter, nor of

seeing Lemmie Quinn enter; now he tells of having seen all of

them enter. Don’t you see how they just made it to fit wit-

nesses and what the witnesses would swear? It was, “Here,

Conley, swear that Quinn came up, swear that the dead girl

came up, and swear that Miss Stover came up; they all did,

and it’s true, swear to it!” And Conley would say, “All right,

boss, Aih reckon they did.” And it was “Conley, how did you

fail to hear that girl go into the metal room? We know she went

there, because by our blood and hair we have proved she was

killed there,” and the poor negro thought a minute, and then

he said, “Yes, (boss, I heard her go in.” The state’s repre-

sentatives had put it into the negro’s head to swear he heard

Frank go in with her, and that he heard Frank come tiptoe-

ing out later, and that by that method they made Conley

swear that Frank was a moral pervert. Now, I don’t know

LEO fM. FRANK. 279

that they told Conley to swear to this and to swear to that,

but they made the suggestions, and Conley knew whom he

had to please. He knew that when he pleased the detectives

that the rope knot around his neck grew looser. In the same

way they made Conley swear about Dalton, and in the same

way about Daisy Hopkins. They didn’t ask him about the

mesh bag. They forgot that until Conley got on the stand.

That mesh lbag and that pay envelope furnish the true motive

for this crime, too, and if the girl was ravished, Conley did it

after he had robbed her and thrown her body into the base.

ment. Well, they got Conley on the stand, and my friend

Dorsey here asked Conley about the mesh bag, and he said,

yes, Frank had put it in his safe. That was the crowning lie

of all!

Well, they’ve gone on this way, adding one thing and an-

other thing. They wouldn’t let Conley out of jail; they had

their own reasons for that, and yet I never heard that old

man over there (pointing to the sherif) called dishonest. He

runs his jail in a way to protect the innocent and not to con-

vict them in this jail.

Gentlemen, right here a little girl was murdered, and it’s

a terrible crime. The Phagan tragedy, the crime that stirred

Atlanta as none other ever did.

We have already got in court the man who wrote those

notes, and the man who by his own confession was there; the

man who robbed her, and, gentlemen, why go further in seek-

ing the murderer than the black brute who sat there by the

elevator shaft? The man who sat by that elevator shaft is the

man who committed the crime. He was full of passion and

lust; he had drunk of mean whiskey, and he wanted money

at first to buy more whiskey.

[Mr. Arnold asked the sheriff to unwrap a chart which had pre-

viously been brought into court. It proved to be a chronological

chart of Frank’s alleged movements on Saturday, April 26, the day

of the crime, and Mr. Arnold announced to the jury that he would

prove by the chart that it was a physical impossibility for Frank

to have committed the crime.]

2X. AMERICAN STATE TRIALS.

Every word on that chart is taken from the evidence, and

it will show you that Frank did not have time to commit the

crime charged to him. The state has wriggled a lot in this

affair; they put up little George Epps, and he swore that he

and Mary Phagan got to town about seven after twelve, and

then they used other witnesses, and my friend Dorsey tried

to boot the Epps boy’s evidence aside as though it were

nothing. The two street car men, Hollis and Mathews, say

that -Mary Phagan got to Forsyth and Marietta at five or six

minutes after twelve, and they stuck to it, despite every

attempt to bulldoze them, and then Mathews, who rode on

the car to -Whitehall and Mitchell, says that Mary Phagan

rode around with him to Broad and Hunter streets before she

got off-

Well, the state put up kMcCoy, the man who never got his

watch out of soak until about the time he was called as a wit-

ness, and they had him swear that he looked at his watch at

Walton and Forsyth (and he never had any watch), and it

was 12 o’clock exactly, and then he walked down the street and

saw Mary Phagan on her way to the factory. Now, I don’t

believe McCoy ever saw Mary Phagan. Epps may have seen

her, but the State apparently calls him a liar, when they intro-

duce other testimony to show a change of time to what he

swore to. It’s certain those two street car men who knew the

girl, saw her, (but the state comes in with the watchless McCoy

and Kendley, the Jew-hater, and try to advance new theories

about the time and different ones from what their own wit-

iless had sworn to. -Well, we have enough to prove the time,

all right; we have the street car schedule, the statement of

Hollis and Mathews and of George Epps, the state’s own

witness.

The next thing is, how long did it take Conley to go through

with what he claims happened from the time he went into

Frank’s office and was told to get the body until he left the

factory. According to Conley’s own statement, he started at

four minutes to 1 o’clock and got through at 1:30 o’clock,

making 34 minutes in all.

280

LEO !. FRANK.

Harlee Branch says that he was there when the detectives

made Conley go through with what he claimed took place, and

that he started then at 12:17, and by Mr. Branch’s figures, it

took Conley 50 minutes to complete the motions. Well, the

state has attacked nearly everybody we have brought into this

case, but they didn’t attack Dr. William Owen, and he showed

by his experiments that Conley could not have gone through

those motions in 34 minutes.

Jim Conley declared that he started at 4 minutes to 1

o’clock to get the body, and that he and Frank left at 1:30.

If we ever pinned the negro down to anything, we did to that,

and we have shown that he could not have done all that in

341 minutes.

Away with your f1ith and your dirty, shameful evidence of

perversion; your low street gossip, and come back to -the

time-the time-element in the case.

Now, I don’t believe the little Stover girl ever went into

the inner office. She was a sweet, innocent, timid little girl,

and she just peeped into the office fr6mn the outer one, and if

Frank was in there, the safe door hid him from her view, or

if he was not there, he might have stepped out for just a

moment.

Oh, my friend, Dorsey, he* stops clocks and he changes

schedules, and he even changes a man’s whole physical

make-up, and he’s almost changed the course of time in an

effort to get Frank convicted.

Oh, I hate to think of little Mary Phagan in this. I hate

to think that such a sweet, pure, good little girl as she was,

with never a breath of anything wrong whispered against her,

should have her memory polluted with such rotten evidence

against an innocent man. Well, Mary Phagan entered the

factory at approximately 12 minutes after 12, and did you

ever stop to fhink that it was Frank who told them that the

girl entered the office when she entered it ? If he had killed

her he would have just slipped her pay envelope back in the

safe and declared that he never saw her that day at all, and

then no one could have ever explained how she got into that

X. AMERICAN” STATE TRIALS.

,basement. But Frank couldn’t know that there was hatred

enough left in this country against his race to bring such a

hideous charge against him. Well, the little girl entered, and

she got her pay and asked about the metal and then she left,

but, there was a black spider waiting down there near the

elevator shaft, a great passionate, lustful animal, full of mean

whiskey and wanting money with which to buy more whiskey.

He was as full of vile lust as he was of the passion for more

whiskey, and the negro (and there are a thousand of them in

Atlanta who would assault a white woman if they had the

chance and knew they wouldn’t get caught) robbed her and

struck her and threw her body down the shaft, and later he

carried it back, and maybe, if she was alive, when he came

back, he committed a worse crime, and then he put the cord

around her neck and left the body there.

Do you suppose Frank would have gone out at 1:20 o’clock

and left that body in the basement and those two men, White

and Denham, at work upstairs? Do you suppose an intelligent

man like Frank would have risked running that elevator, like

Conley says he did, with the rest of the machinery of the fac-

tory shut off and nothing to prevent those men up there hear-

ing him?

Well, Frank says he left the factory at I o’clock, and Con-

ley says he left there at 1:30. Now, there’s a little girl, who

tried the week before to get a job as stenographer in Frank’s

office, who was standing at Whitehall and Alabama streets,

and saw Frank at ten minutes after 1. Did she lie? Well,

Dorsey didn’t try to show it, and according to Dorsey, every-

body lied except Conley and Dalton and Albert McKnight.

This little girl says she knows it was Frank, because Professor

Briscoe had introduced her to him the week before, and she

knows the time of day because she had looked at a clock, as she

had an engagement to meet another little girl. That stamps

your Conley story a lie blacker than hell! Then, Mrs. Levy,

she’s a Jew, but she’s telling the truth; she was looking for

her son to come home, and she saw Frank get off the car at

his home corner, and she looked at her clock and saw it was

282

1:20. Then, Mrs. Selig and Mr. Selig swore on the stand that

they knew he came in at 1:20.

Oh, of course, Dorsey says they are Frank’s parents and

wretched liars when they say they saw him come in at 1:20.

There’s no one in this ease that can tell the truth but Conley,

Dalton and Albert McKnight. They are the lowest dregs and

3ail-birds, and all that, but they are the only ones who know

how to tell the truth! Well, now Albert says he was there at

the Selig home when Frank came in; of course he is lying,

for his wife and the Seligs prove that, ibut he’s the state’s

witness and he says Frank got there at 1:30, and thus he

brands �Conley’s story about Frank’s leaving the factory at

1:30 a lie. Well, along the same lines, Albert says Frank

didn’t eat and that he was nervous, and Albert says he

learned all this by looking into a mirror in the dining room,

and seeing Frank’s reflection. Then Albert caps the climax

to his series of lies by having Frank board the car for town

at Pulliam street and Glenn.

Now as to the affidavit signed by Minola MeKnight, the cook

for Mr. and Mrs. Emil Selig. How would you feel, gentlemen of

the jury, if your cook, who had done no wrong and for whom

no warrant had been issued, and from. whom the solicitor had

already got a statement, was to be locked up? Well, they got

that wretched husband of Minola’s by means of Craven and

Pickett, two men seeking a reward, and then they got Minola,

and they said to her, “Oh, Minola, why don’t you tell the

truth like Albert’s telling it?”

They had no warrant when they locked this woman up.

Starnes was guilty of a crime when he lockdd that woman

up without a warrant, and Dorsey was, too, if he had

anything to do with it. Now, George Gordon, ]Ainola’s law-

yer, says that he asked Dorsey about getting the woman out,

and Dorsey replied, “I’m afraid to give my consent to turn-

ing her loose; I might get in bad with the detective depart-

ment.” That’s the way you men got evidence, was it?

Miss Rebecca Carson, a forewoman of the National Pencil

factory, swore Frank had a good character. The state had

LEO M. FRAN2K.

283

X. AMERICAN STATE TRIALS.

introduced witnesses who swore that the woman and Frank

had gone into the woman’s dressing room when no one was

around. I brand it a culmination of all lies when this woman

was attacked. Frank had declared her to be a perfect lady

with no shadow of suspicion against her.

Well, Frank went on back to the factory that afternoon

when he had eaten his lunch, and he started in and made out

the financial sheet. I don’t reckon he could have done that if

he had just committed a murder, particularly when the state

says he was so nervous the next morning that he shook and

trembled.

Then, the state says Frank wouldn’t look at the corpse. But

who said he didn’t? Nobody. Why, Gheesling and Black

dcidn’t swear to that.

Now, gentlemen, I’ve about finished this chapter, and I

know it’s been long and hard on you and I know it’s been

hard on me, too; I’m almost broken down, but it means a lot

to that man over there. It means a lot to him, and don’t for-

get that. This case has been made up of just two things-

prejudice and perjury. I’ve never seen such malice, such per-

sonal hatred in all my life, and I don’t think anyone ever has.

The crime itself is dreadful, too horrible to talk about, and

God grant that the murderer may be found out, and I think

he has. I think we can point to Jim Conley and say there is

the man.

But, above all, gentlemen, let’s follow the law in this mat-

ter. In circumstantial cases you can’t convict a man as long

as there’s any other possible theory for the crime of which

he is accused, and you can’t find Frank guilty if there’s a

chance that Conley is the murderer. The state has nothing

on which to base their case but Conley, and we’ve shown Con-

ley a liar. Write your verdict of not guilty and your con-

sciences will give your approval.

August 1913 Speech Above

–

October 1913 Speech Below

THE TRIAL OF LEO FRANK

Speech of Mr. Arnold

MAY IT PLEASE YouR HONOR:

It takes thirteen jurors to murder a man

in cold blood. So that I feel I am not only justified

but required, by the scope of Your Honor’s authority

and duty and the tremendous responsibility that rests

upon you, to argue to the court the facts of this un-

usual case, and to give the reasons why the verdict of

guilty should be set aside and a new trial granted.

In many respects, this is an unusual case. Unfor-

tunately, murder is a frequent crime. The example

of Cain is too often followed in this vale of tears, and

this very community has had many killings that were

horrible to contemplate.

That fact does not mitigate this offense, of course,

in any degree-and this was an atrocious deed-but

I do say, that while we have seen murder here as cruel

as this, we have had no such trial as this.

The feeling here grows out of something over and

beyond the mere facts of the crime, and if you will

look down a little under the surface you will find the

cause to be the one that has run down the ages and

shed innocent blood for twenty centuries.

The Trial of Leo Frank

A trial is going on to-day in Russia that parallels

this case. A Jew is there being tried for a ritual

murder of a thirteen-year-old boy. The naked evi-

dence against him makes a terrible case; but the civil-

ized world stands aghast at it, looks upon it with

horror, and knows that the attempt to connect that

man with the murder is but the hideous appearance

again of that racial prejudice that has reflected no

credit for two thousand years upon the race to which

Your Honor and I belong.

I feel, Your Honor, that the time is coming when

the whole human race will be one great brotherhood.

Some day all of this prejudice will cease to exist.

That day is already here with enlightened people;

and it is here with some of the benighted part of the

population when they allow their better feelings to

prevail.

We have the best people on earth in this Southern

country. We are really the only American part of

this Republic; and I know that when our people

finally think and feel on a subject like this they will

come to a decision divested of all prejudice and find

only truth.

As long, though, as there is an element pushing itself

into a courthouse to disgrace the community by

applause and demonstration, a great many people are

going to take that as manifestation of the public senti-

ment. They forget the thousands of good people who

are up in the offices, in the shops, in the stores. They

take it for granted that the public sentiment is shown

Mr. Arnold’s Address to the Court

by the acts of those persons who have nothing to do

except to crowd into a courthouse where a poor fel-

low is on trial for his life, and who cheer, and whose

faces light up with smiles when he is found guilty,

and who rejoice and shake hands with each other and

throw up their caps in glee over the fact that a man

is sentenced to die. That was the spirit that clung

to the Frank trial.

I was reading in this morning’s newspaper an article

from the pen of a writer who was undertaking to

account for congregations of men-mobs, we call

them-perpetrating deeds of atrocity when ordinarily

and naturally a man as an individual is kind. He

said the spirit of the mob was not the spirit of any

one mind, but the fusion of many and their effect

upon each other, just as you mix many chemicals and

produce a result different and apart from the quality

of any one chemical that entered into the mixture.

And how deadly is the spirit of the mob! When

the great War President Lincoln was assassinated-

cruelly killed by a fanatic who represented naught

but his own disordered brain–so wild were the people

in civilized Washington, the seat of government, of

enlightenment, of culture, that they committed a

crime which compared with the assassination itself.

They put to death six or seven people charged with

being members of a conspiracy to assassinate the

President. Among those put to death was a poor

woman, Mrs. Surratt, admitted now by everybody,

North and South, to have been guiltless of the crime.

The Trial of Leo Frank

Sentiment, prejudice, excitement, had taken the place

of justice.

And so it was when Frank was tried! An intense

prejudice on the part of ignorant people sometimes

overlaps that class and spreads into other circles by

the mere fact of its existence.

Your Honor, there should have been but a single

question in the Frank case, and there should have

been no feeling in arriving at the truth. I never

could understand how anybody could be prejudiced

about ascertaining a fact. Why should there be any

feeling in simply determining the question, Did A kill

B? Yet we were so overwhelmed with it that all

energies were bended in an effort to overcome the

influence of the crowd that piled around us, blocked

our way from and to the court, applauded in and out

of court, and scowled menacingly at Frank. The

looks of murder that appeared in human eyes reached

court, lawyers, witnesses, jurors.

Argument was lost upon that jury. Proving facts

was but casting pearls before swine. There they sat,

huddled like twelve sheep in the shambles. Talk to

me about those jurors not having been influenced by

such surroundings! They may not know they were.

Nor did the rabbit that ran through the briar patch

know which briar scratched and which did not.

I venture to say if this case had been tried where it

had never been heard of before, without the feeling,

the prejudice and excitement which clustered about

it here, with Your Honor as the judge, and before

Mr. Arnold’s Address to the Court

a fair and impartial jury with minds unstained by

whispered lies and white as unsoiled sheets of paper,

there would not have been a moment’s hesitation

about the verdict.

Why should there be? Was ever a case heard of

before where the only witness on whose testimbny the

conviction rested was a party to the crime, both before

it was committed, by watching, and after it was com-

mitted, by helping to conceal the body; was a crimi-

nal of the lowest type and as absolutely devoid of con-

science as a man-eating tiger; one who lied in writing

four different times, and who never confessed any-

thing about the crime until the dead evidence was

discovered on him that he had written the notes that

accompanied the body; who admitted he lied many

times in his affidavits; and where, after he made his

last affidavit, the story that he brought into court was

so unlike it that you could hardly recognize any points

of similarity; and where he changed his story seven

different times when he went over the subject with the

Solicitor General?

As my lamented friend Charlie Hill used to say,

“Did ever one hobble to a verdict on such a rotten

pair of crutches?” Does Your Honor believe that a

worm that crawls in the dust would have been con-

victed on such testimony under ordinary and usual

circumstances?

Admitting he lied scores of times in matters of sub-

stance and in immaterial matters, a criminal from

birth practically, without character, without stand-

The Trial of Leo Frank

ing, with every motive to lie, with his own neck to

save, Conley was so plastered over with contradic-

tions that it’s monstrous to argue his testimony.

And yet people say he stayed on the stand three

days without breaking down! He did stay there

physically three days, and all the wretch would say

when you got him outside of the story he was fixed

and prepared on was “I don’t know,” or “I lied about

that,” or “I don’t remember.” You can teach a

parrot, “Polly wants a cracker,” and he will say it six

months, and he won’t break down on it either unless

you take a club and knock him down.

An idea seems to be abroad that a lawyer has to

hypnotize a witness and get him to talk in a trance

before he is discredited. If a witness’s testimony is

unreasonable or unbelievable, that witness is broken

down in the legal sense. If Rosser’s bombardment

didn’t finish Conley, then there was no way it could

be done except by cleaving him with a battle-axe.

There are many parts of the record here showing

what marvelous assistance Conley had in the prepa-

ration of his story before he was ever brought into

court to testify. When Conley told something that

didn’t fit in with the undeniable facts of the crime, the

undisputed logic of the situation, his attention was

promptly called to it by these officers who had him

in charge and were nursing him, and the story was

changed; when he made a statement that did not cor-

respond with the views held by the police the tale was

reconstructed.

Mr. Arnold’s Address to the Court

Left alone, the negro spread out over the whole

territory of asininity; but they took his story like

you would take a rough piece of timber and fashion

it over with the power of machinery. I have counted

in this record twenty-nine lies that Detective Scott

testified Jim Conley told to him and Detective Black

that they got him to correct. Twenty-nine lies that

they prevailed upon him to change! Not little,

technical lies, but big, fat, substantial lies. This

is not a mere conclusion of mine. The record is

the proof.

Your Honor remembers from the evidence how the

negro’s story grew. When the search was on to find

the writer of the notes there was no doubt in any-

body’s mind, of course, that the writer of the notes

was the murderer of the girl. That fact would admit

of no dispute. Conley was denying that he could

write. The discovery was made, however, that he

could write and the evidence gathered that he was

the author of the notes. Conley saw no way to save

his miserable neck except to say he had written them

for some one else.

Frank had been held under suspicion. One bank

official of the city had even said that a comparison of

the notes with the handwriting of Frank indicated

they were written by him. Many stories of unknown

origin were circulated everywhere. The cry rang out,

“The d- Jew did it.” Slanders against Frank

were poured in the people’s ears. He was locked up

in jail and had no chance to meet them. The seeds

15

The Trial of Leo Frank

of prejudice were sown broadcast and Frank was con-

demned in the public mind.

Conley saw this and he saw his own life trembling

in the balances. He was compelled to say that some

one else was the real author of the notes or else give

up his life; and he named Frank as the man. He

said he had done the writing at Frank’s dictation on

Friday-the day before the murder.

Well, of course, that was a ridiculous, unreasonable

lie. Mr. Dorsey does not contend that the killing

was premeditated, that Frank knew on Friday he

was going to kill the girl on Saturday. But Conley,

in his savage ignorance, saw not the unreasonableness

of the story and insisted that he had done the writing

on Friday.

Now, what happened? Let me read from Scott’s

testimony. Scott says:

We talked very strongly to Conley. We saw him on

May 27th in Chief Lanford’s office. We talked to him five

or six hours. We tried to impress him with the fact that

Frank would not have written those notes on Friday; that

that was not a reasonable story. That showed premedita-

tion, and that would not do. We pointed out to him why

the first statement would not fit. We told him we wanted

another statement. He declined to make it. He said he

had told the truth. On May 28th Chief Lanford and I

grilled him for five or six hours again, endeavoring to make

clear several points which were far-fetched in his state-

ment. We pointed out to him that his statement would

not do and would not fit. He then made us another long

statement.

Mr. Arnold’s Address to the Court

On May 29th we had another talk with him; talked with

him almost all day. Yes, we pointed out things in his story

that were improbable, and told him he must do better

than that. Anything in his story that looked to be out

of place we told him wouldn’t do.

Great God! It sickens me. I shudder to think of

the deeds perpetrated in this case-the methods used

to bring this man to his destruction.

Take the Minola McKnight episode. Mr. Dorsey

says:

I honor the way they went after Minola McKnight.

Now, let us see what his standard of honor is.

Here was a poor, humble, negro woman, an employee

of Frank’s household: the husband who had sworn to

protect her had turned against her and she was help-

less and alone. She is taken down to Mr. Dorsey’s

office, and there she makes a full statement showing

that she knows nothing incriminating against her

employer. That is sworn to and the Solicitor has it

in writing.

Now, Dorsey honors the fact that later the detec-

tives get her and bring her back to his office, where she

is confronted with her husband, who tries to get her

to agree that the stories he is telling are true. Dorsey

honors the fact that when she refused to agree they,

in flagrant violation of law, and in a way that never

would have been perpetrated on a man who could

assert his rights, took her to the station house with-

out warrant or charge of crime, and there compelled

The Trial of Leo Frank

her, behind iron bars, in tears, and before uniformed

and armed officers, brass buttons and pistols, to agree

that the villainous lies her husband told were true.

That’s what he honors: and it seems the jury and

the crowd honored it, too. Was this a mere technical

right that was violated? Not so; and yet, without

technical rules, Might would always triumph over

Right. Our race has experimented in government

for centuries, not as vassals, but as sovereigns; and

certain laws that have stood the test of time have

been adopted to guide us between governmental

tyranny on the one hand and anarchy on the other.

Technicalities they may be, but if they are destroyed

one may as well camp out in the woods and let the

strongest man prevail. They are the refined wisdom

of the ages.

Hear Dorsey again:

I don’t know whether they want me to apologize for

that or not, but if you think that finding the red-handed

murderer of a little girl like this is a ladies’ tea party, and

that the detectives should have the manners of a dancing

master, and apologize and palaver, you don’t know any-

thing about the business.

Oh, no, we didn’t expect that; but we did expect

them not to violate the criminal laws of the country;

we did expect them, when a witness had had a full

and fair chance to make a statement, to let her alone;

not to violate the laws of God and man, and put the

thumbscrews and torture to her and lock her in a

Mr. Arnold’s Address to the Court

prison cell to make her change her statement. We

did expect that; and you wouldn’t have had to balk

at tea parties either: you could have gone further

than that.

May it please Your Honor, those are some of the

methods that have been used against the man over

yonder in that jail who is condemned to death on as

base a fabrication as was ever constructed in darkest

Russia.

Your Honor, I speak plainly because I am so con-

stituted by Nature that I cannot call a spade any-

thing except a spade. I am looking through all

the surrounding paint and varnish to see the hideous

thing inside of this prosecution, and it sickens me to

think that man in jail is in peril from such methods.

There is no evidence against him in this case except

such as comes from Jim Conley, that prince of liars.

You could no more impeach Conley by showing he

had lied than you could saturate a duck by pouring

water down its back. He is impervious to a charge of

lying. He will admit it any day in the week.

But Mr. Dorsey, realizing what a burden Conley is

for him to carry, says Conley is not the only evidence

in the case. For instance, he says the expression, “It

is too short a time since you left for anything startling

to have developed down here,” in a letter written by

Frank on the day of the tragedy, shows guilt. Ex-

pressions of this character are extremely common in

letters; but Mr. Dorsey says it proves that something

startling had happened and that the writer had killed

19

The Trial of Leo Frank

Mary Phagan. That deduction of Mr. Dorsey’s is

just as sound as any other he has drawn.

In this letter, which was written on Memorial Day

to Frank’s uncle, himself a Confederate Soldier, the

writer also refers to the “thin gray line of veterans

braving the chilly weather to honor their fallen com-

rades.” I would be glad to hear even an Arab of the

desert speak kindly of these men, but Mr. Dorsey sneers

at this tribute Frank paid the old soldiers in gray.

Everything that Frank did has had an unfair con-

struction placed upon it, and is looked upon as a cir-

cumstance of guilt and sufficient reason for his con-

demnation.

It reminds me of the fable of the wolf and the lamb.

The wolf was going to kill the lamb for muddying the

water. “But,” said the lamb, “you are drinking

above me in the run of the stream.” “Well,” said

the wolf, “I don’t care; your grandfather muddied it

once and I am going to get you anyhow.”

Mr. Dorsey also refers to the telegram sent by

Frank on Monday to Adolph Montag, telling him of

the finding of the body in the cellar of the pencil

factory. Dorsey says:

In factory? In factory? No, “in cellar.” Cellar where?

“Cellar of pencil factory.”

There was no sense in all this talk of Mr. Dorsey’s

but there was plenty of sound and that was satis-

factory to the jury.

Yes, she had been found in the “cellar of the pencil

Mr. Arnold’s Address to the Court

factory.” The police had come for Frank and carried

him down there. The story would be in all the

papers. Many rumors were being started. Frank,

the superintendent of the factory, wired Montag, one

of the owners of the factory, telling him of the tragedy

and asking him to assure his uncle he was all right in

case he asked.

Is there anything incriminating here? No fair

mind can find it. But all Dorsey had to do with

that gang of wolves out there in the audience was to

turn and look at them and they would beam on him

with bloody satisfaction. They were trying to take

the life of a fellow creature in holiday fashion and

Frank was the butt end of that Roman holiday.

Again, they say that when Helen Ferguson received

her pay on Friday she also asked for Mary Phagan’s

pay envelope and that Frank refused to give it to her.

Even if this had happened it would have been no

evidence of guilt and would have proved nothing.

It was not usual to give one person’s pay envelope to

another except on proper request.

But it is overwhelmingly a mistake. In the first

place the evidence shows that on Friday Frank did

not pay off the employees but that Schiff did.

Furthermore, Magnolia Kennedy testified that she

waswith Helen Ferguson when they both received their

pay, that they received their envelopes from Schiff,

not from Frank, that they left the factory together

and that the witness Ferguson did not ask for any-

body’s pay except her own.

21

The Trial of Leo Frank

Further, Mr. Dorsey says that when these notes

that were found by the body of the dead girl were

shown to Frank, he should have then and there said:

“This is the writing of James Conley.”

Frank, locked up in his prison cell, did not know

at that time that Conley was denying he could write,

and had no reason to think that specimens of Conley’s

handwriting had not already been compared with the

notes. None of these officers had told Frank that

Conley claimed he could not write.

Moreover, Frank did not know the handwriting of

Conley and there is no proof that he did. It is true

that he had seen Conley’s writing but there was no

individuality about it sufficient to impress itself upon

one’s memory. Even between these two notes them-

selves there is little similarity. You could not testify

they were written by the same man.

While there are classes of people–professors of

penmanship, bank tellers, etc.,-who seem to store

away an impression of handwriting in the mind and

recognize it when they see it again as if it were a

human face, yet to most people there is only a gener-

ality about handwriting and seldom indeed it is that

one retains a mental picture of the writing of the

average negro. Why, even Mr. Berry, the bank teller

who studied those notes and who studied the hand-

writing of Newt Lee, named Lee as their author.

Holloway, Darley, Schiff, Wade Campbell and

others had also seen Conley’s writing, but it never

occurred to them when they looked at the notes that

22

Mr. Arnold’s Address to the Court

they were written by Conley. Surely, if this is a cir-

cumstance of guilt it is as strong against these men as

it is against Frank. Mr. Dorsey, though, does not

claim that they had any part in the killing of this

child. Moreover, Frank did not know that Conley

had been to the factory on this holiday. No one

seemed to have seen him. Mrs. White had said she

saw some negro about the stairway; and, according

to Detective Scott’s evidence, Frank gave him this

information on Monday following the tragedy. What

more could Frank have done? And would he have

done that if he had been Conley’s accomplice?

But they say Frank was so excited and nervous over

the murder on Sunday morning that he “trembled

like an aspen.” If he was nervous it was the sight of

the dead girl and the discovery of such a tragedy

enacted in the factory under his charge that made him

nervous. He was not nervous on Saturday afternoon

when he prepared the financial sheet that the fore-

most experts of the South say would require several

hours’ work. It has been overwhelmingly established

that he did that work on Saturday afternoon, and yet

there is not a trace of nervousness in all that mass of

figures, in all that intricate, complicated work. A con-

sciousness of guilt would have made him nervous

then. But there was no nervousness then, for he

knew not at that time that the corpse of the little girl

was down there in the basement beneath him.

And yet on such argument as that, and amid such

surroundings as those, an innocent man is condemned

23

The Trial of Leo Frank

to die I There is not a proven circumstance in this

case that cannot be shown to the satisfaction of any

reasonable man that it is not a circumstance of

guilt on the part of this defendant.

Why, may it please Your Honor, the physical facts

of this case show that this crime could not have been

committed by Leo M. Frank. The parents of the

little Phagan girl swore she left Bellwood–out there

two miles from the city-at 1I:50 A. mL. That little

State’s witness Epps says he got on the car with her.

Neither the conductor nor the motorman saw him,

but he says he got on with her and got off at Forsyth

and Marietta Streets at 12:07. Detective Starnes

says it took him from three and a half to four minutes

to walk from that point to the pencil factory.

According to the State’s own witness, therefore, the

little girl could not possibly have reached the pencil

factory sooner than ten and one half minutes after

twelve. Epps was the first witness the State put up,

and the State soon realized he had crushed their case,

and began to wriggle to get away from their own

testimony.

The motorman says she rode all the way around

Broad Street to Hunter Street and got off there at