Another in our series of new transcriptions of contemporary articles on the Leo Frank case.

Another in our series of new transcriptions of contemporary articles on the Leo Frank case.

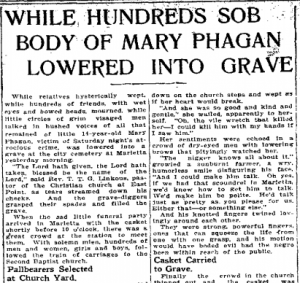

Atlanta Constitution

Wednesday, April 30th, 1913

While relatives hysterically wept, while hundreds of friends, with wet eyes and bowed heads, mourned, while little circles of grim visage men talked in hushed voices of all that remained of little 14-year-old Mary Phagan, victim of Saturday night’s atrocious crime, was lowered into a grave at the city cemetery at Marietta yesterday morning.

“The Lord hath given, the Lord hath taken, blessed be the name of the Lord,” said Rev. T. T. G. Linkous, pastor of the Christian church at East Point, as tears streamed down his cheeks. And the grave-diggers grasped their spades and filled the grave.

When the sad little funeral party arrived in Marietta with the casket shortly before 10 o’clock, there was a great crowd at the station to meet them. With solemn mien, hundreds of men and women, girls and boys, followed the train of carriages to the Second Baptist church.

Pallbearers Selected at Church Yard.

So unstrung was everyone connected with the tragedy that no details had been looked after. It was upon the church grounds that the pallbearers, L. M. Spruell, B. Awtrey, Ralph Butler and W. T. Potts, were selected.

With the little white casket on their shoulders, they walked into the tiny country church. Then the crowd poured in. Within five minutes every pew had been taken, every available inch of standing room was occupied and hundreds, who could not get in, were standing on their tiptoes on the steps, trying to catch a word of the services.

With voices that cracked because of choked back tears, yet were sacred because of the feeling behind them, the choir sang “Rock of Ages.” A dozen times during every stanza they were interrupted by the wailings of the bereaved mother.

Not a Dry Eye in Church.

Before the hymn had been sung through, there was scarcely a dry eye in the whole church. And from that time on the incessant sound of muffled sobbing seemed to sanctify the services, like some rich old chant of the days gone by.

Dr. Linkous rose to the pulpit.

“Let us pray,” he said.

In a voice that, though hushed, seemed to reverberate through the hole [sic] edifice, he asked for power that he might pray as he should. “The occasion is so sad to me—when she was but a baby, I taught her to fear God and love Him—that I don’t know what to do,” he said.

As he continued, a new eloquence seemed to creep into his voice. Tears gushed from his eyes, and he let them course down his face without attempting to brush them off, yet every moment seemed to bring new power, new strength to him.

“We pray for the police and the detectives of the city of Atlanta,” he said. “We pray that they may perform their duty and bring the wretch that committed this act to justice. We pray that we may not hold too much rancor in our hearts—we do not want vengeance—yet we pray that the authorities apprehend the guilty party or parties and punish them to the full extent of the law. Even that is too good for the imp of satan that did this. Oh, God, I cannot see how even the devil himself could do such such [sic] a thing.”

“Amen!” Cries Aged Grandfather.

When he made the allusion to the criminal, the faces of those on the front pews, where the family sat, seemed to tighten. The mother stopped crying for a moment, and the aged grandfather exclaimed, “Amen.”

“I believe in the law of forgiveness,” continued the clergymen. “Yet I do not see how it can be applied in this case. I pray that this wretch, this devil, be caught and punished according to the man-made, God-sanctioned laws of Georgia. And I pray, oh, God, that the innocent ones may be freed and cleared of suspicion.”

It was at this point that Miss Lizzie Phagan, aunt of the victim of the crime, shrieked wildly, and, as the result of her overwrought emotions, dropped fainting from her seat. She was carried out to a carriage and taken home.

Dr. Linkous alluded in his sermon to the crime as possibly an agent of God in a grotesque guise.

“Mothers,” he declared vehemently, “I would speak a word to you. Let this warn you. You cannot watch your children too closely. Even though their hearts be clean and pure as that of not be forced into dishonor and into the grave by some heartless wretch, like the guilty man in this case.

Only Consolation I Can Offer.

“Little Mary’s purity and the hope of the world above the sky is the only consolation that I can offer you,” he said, speaking directly to the members of the bereaved family. “Had she been snatched from our midst in a natural way, by disease, we could bear up more easily. Now, we can only thank God that though she was dishonored, she fought back the fiend with all the strength of her fine young body, even unto death.

“All that I can say is God bless you. You have my heartfelt sympathy. That is all that I can do, for my heart, too, is full to overflowing.”

When Dr. Linkous concluded, the casket was opened, and the crowd was allowed to pass up and see, for the last time, the face of the girl that was so beloved in the little country village that she once called home.

Although almost everyone passed the coffin, it was not the morbid crowd that thronged the undertaking parlors while the body was there. Real feeling, real sorrow, was exhibited as the mournful procession wended its way around the bier.

Many tears, silent tributes to the dead girl, dropped down on the flowers that surrounded her mutilated face.

Her Playmate Breaks Down.

Annie Castile, a 19-year-old girl who worked with Mary at the knitting mills at Marietta three years ago, broke down completely when she saw the body.

Hysterically sobbing, she was led out of the church by friends. Caring nothing for her neat, tailored dress, not seeming to notice the hundreds of eyes that were focussed [sic] on her, she sank down on the church steps and wept as if her heart would break.

“And she was so good and kind and gentle,” she wailed, apparently to herself. “Oh, the vile wretch that killed her—I could kill him with my hands if I saw him.”

Her sentiments were echoed in a crowd of dry-eyed men with lowering brows that pityingly watched her.

“The nigger knows all about it,” growled a sunburnt farmer, a wry, humorless smile disfiguring his face. “And I could make him talk. Oh yes. If we had that scoundrel in Marietta, we’d know how to get him to talk. We’d make him be polite. He’d talk just as pretty as you please for us. Either that—or something else.”

And his knotted fingers twined lovingly around each other.

They were strong, powerful fingers, ones that can squeeze the life from one with one grasp, and his motion would have boded evil had the negro been within reach of the public.

Casket Carried to Grave.

Finally the crowd in the church thinned out, and the casket was brought out. Mrs. Phagan was half carried out, her husband, J. W. Coleman on one side of her, and Dr. Linkous on the other. Behind them walked the sorrowing sister, with her brother Ben, a sailor from the United States ship Franklin, who arrived in Atlanta Monday night. The smaller brothers, Joshua and Charlie, brought up the rear.

While the hearse and carriages went around the road to the cemetery, the great crowd poured over the railroad tracks to the cemetery.

Dr. Linkous spoke briefly at the grave. The old comforting lines, “Earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust,” did not seem to comfort even him, and he broke off his prayer, as if he thought that time alone, and no words on earth, could heal the wounds that had been made in the hearts of the family.

When the first shovelful of earth was thrown down into the grave Mrs. Phagan broke down completely. Half deliriously, she raved of her daughter.

Taken Away When Spring Was Coming.

“She was taken away when the spring was coming—the spring that was so like her. Oh, and she wanted to see the spring. She loved it—it loved her. She played with it—it was a sister to her almost.”

On she wailed. Her husband tried to quiet her, but he failed. She crept up to the edge of the grave, and taking from the clergyman’s hand the handkerchief that he had been using to wipe away her tears, she waved it.

“Goodby [sic], Mary,” she sobbed. “Goodby. It’s too big a hole to put you in though. It’s so big—b-i-g, and you were so little—my own little Mary!”

* * *

Atlanta Constitution, April 30th 1913, “While Hundreds Sob Body of Mary Phagan Lowered into Grave,” Leo Frank case newspaper article series (Original PDF)